Interpreting Ceramics | issue 13 | 2011 Articles & Reviews |

|

|||||||

|

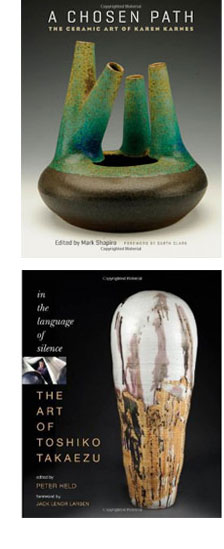

Book Reviews by Moira Vincentelli A Chosen Path, the Ceramic Art of Karen KarnesEditor: Mark Shapiro with foreword by Garth Clark and contributions by

In the Language of Silence, the Art of Toshiko TakaezuEditor: Peter Held with foreword by Jack Larsen and contributions by

|

|

|||||||

|

Both Karnes and Takaezu were born in the 1920s and have continued to be active through to the twenty-first century producing some of their most impressive work in scale and ambition at an age when many others have retired. Although the book on Karen Karnes was published to accompany a major retrospective show at Arizona State University and might be said to be a catalogue, the format of the publications is similar, bringing together a collection of essays of varying length and approach, from the academic to the personal, accompanied by beautiful colour illustrations of the works and documentary photographs of the life. For these women of independent spirit, clay opened up the possibility of life styles and opportunities that were very different from their early background. Karnes is the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants in New York where people mainly worked in the textile trade; and Takaezu, the sixth of eleven children of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii. The latter first trained in pottery in Hawaii but in 1951 decided to continue her studies in North America. She chose the leading design school, Cranbrook Academy in Michigan, having seen an image of work by the Finnish ceramic artist and designer, Maija Grotell, who became her mentor, friend and life-long inspiration. With her fellow student, Jeff Schlanger, she co-wrote a book on Grotell and I once witnessed her enthusiasm and devotion to this quiet teacher at a presentation she gave at a conference in Finland. An eight month trip to Japan in 1955 allowed her to make direct contact with her personal heritage but significantly she was most attracted by the avant-garde especially the ceramic artist, Yagi Kazuo and the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Typical of her generation Takaezu was trained as a ‘designer craftsman’ and has also worked in bronze, weaving and painting. For much of her life she was a teacher at Cleveland Institute of Art and later at Princeton (1967-92) but she also took on apprentices expecting of them to share her daily discipline and activities which included yoga and gardening. As she said, ‘In my life I see no difference between making pots, cooking and growing vegetables. They are all related’. There is a sense with Karen Karnes that she had the happy knack of being in the right place at the right time as her life story is peppered with connections with significant modernist artists. During her early studies in New York she was picked out by the innovative architect and designer, Chermayeff, as his best student. Between 1949-51 she was in Italy where she learned to throw and came into contact with the new design ideas of post-war Italy. After a brief period at Alfred she moved to another hotbed of new ideas at Black Mountain College where she and her husband, David Weinrib, were the potters in residence. This brought them into contact with leading experimental modernists and it was also here that she first met Shoji Hamada when he toured the US with Bernard Leach in 1952. Hamada is on the list of inspiring artists for both Karnes and Takaezu. In 1954 Karnes and her husband became founding members of the Gate Hill Community in New York State where fellow artists included the musician John Cage and the dancer Merce Cunningham. After 1959, when Weinrib moved to New York City she raised her son, born in 1957, in this supportive alternative community remaining there for twenty-five years. In 1968 she met Ann Stannard, the potter and kiln-builder, who became her life companion. Ann Stannard was a British art teacher who had a house and studio in Anglesey in North Wales but settled in the US moving with Karnes to Vermont after 1979. They built wood-fired kilns first at Danville and later rebuilt at Morgan. Although she was regularly invited to do workshops and short–term teaching, essentially Karnes has earned her living as a potter throughout her life. Her flameproof casserole dishes were a particular success over decades. With hindsight it can be seen that Karnes was always ready to take on new ideas – first with stoneware, then with bold orange-peel salt-glaze and latterly with wood-fired stoneware with subtly even suggestively modulated forms with multiple spouts. One suspects that that the work of Louise Bourgeois would not have escaped her notice. The publication is a compilation of essays from a stimulating variety of writers who offer different perspectives on her life and work. From a gallerist and writer, Garth Clark, who showed her work, the potter and writer Mark Shapiro, the critic Janet Koplos and the writer and curator, Jody Clowes who offers a welcome discussion of her life in the context of the decades of Second Wave feminism. Christopher Benfey’s essay ‘An American Life in Seven Contrast’ picks out some provocative contrasting themes – studio and factory; craft and modernism; east and west. Edward Lebow writes a close reading of her pots. Finally there is an essay by Karnes herself telling the story ‘In her own words’ – from finding clay, back to the land and through to ‘trial by fire’ when, in 1998, her house and studio burnt down – a potter’s tale indeed. The softer gentler forms of her later work she writes ‘grew directly from the trauma of the fire, and it was a welcome one.’ Given the pivotal nature of this event there is an unfortunate typo in the chronology at the back which sets the fire a decade earlier. The book on Takaezu is edited by Peter Held who has been involved in both publications. It uses a similar format but in this case the key essay is by Janet Koplos taking us through a discussion of her work from the early groupings and multi-spouted vessels in the 1950s – pre-dating the work of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott by three decades and inevitably making comparison with Karnes’ late work. The introduction of sound also seems like a remarkably prescient idea. Apparently a chance occurrence of trapping a little piece of clay inside the pot became a feature of many of her closed form ceramics. She considers this as a form of sending messages through the ‘sound of the pot’ and it is even suggested that she wrote poems on the inside of some of her works. It was after the 1980s, however, that her ceramics clearly took on a more conceptual turn, witness to her openness to embrace new ideas. Especially after her retirement from teaching in 1992, she began to make large scale installation pieces often related to female or ecological themes. In Gaea (Earth Mother) two of her circular moon forms were suspended in hammocks to create a dramatic and poetic composition. Both these publications are fitting tribute to two ceramic artists who have worked over a period of six decades responding to their times and pushing way beyond the cosy comfort zone of their starting point in domestic pottery. |

||||||||

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated |

||||||||

Book Reviews by Moira Vincentelli • Issue 13 |

According to the poster issued by the feminist artist(s), the Guerrilla Girls, one of the ‘advantages of being a woman artist is ‘knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty’. It has indeed been a common pattern for many twentieth century women artists that their careers get acknowledged late in their lives. Living well into their eighties (although sadly Toshiko Takaezu died in March 2011), both Karnes and Takaezu have had some recognition in their field over the decades, however these books represent the most complete and ambitious record of their achievements and reveal how they have often been ahead of their time.

According to the poster issued by the feminist artist(s), the Guerrilla Girls, one of the ‘advantages of being a woman artist is ‘knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty’. It has indeed been a common pattern for many twentieth century women artists that their careers get acknowledged late in their lives. Living well into their eighties (although sadly Toshiko Takaezu died in March 2011), both Karnes and Takaezu have had some recognition in their field over the decades, however these books represent the most complete and ambitious record of their achievements and reveal how they have often been ahead of their time.