Interpreting Ceramics | issue 14 | 2012 Conference Papers & Article |

|

|||||||

What Difference can a Description Make?Michael Hose |

|

|||||||

|

In his catalogue essay for the exhibition A Rough Equivalent: Sculpture and Pottery in The Post-War Period,1 held at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, in 2010/11, Jeffrey Jones explores, examines and makes cogent arguments for strong connections between the two disciplines, concluding ‘that there is a shared aesthetic between the two disciplines of ceramics and sculpture, despite the fact that there is little in the way of shared history’. But it could also be argued that it is often the case that these ‘shared aesthetic’ features are articulated in quite different ways within ceramics, to those in sculpture, whether it be the artist or maker talking about their work, or those who may be writing about it. Probably the most noticeable difference is in the ways artworks or artistic practices are described, evaluated and discussed. The ‘shared aesthetic’ would become more tangible, with significant benefits accruing for those practicing within ceramics, if the aesthetic features of artworks or other artifacts, were always described in informed, clear and consistent ways. For those conducting research within the visual arts and crafts, this is axiomatic. Findings arising from the literature searches and field reviews of those undertaking doctoral projects at Cardiff School of Art and Design, revealed that very little was available in terms of adequate descriptions of the aesthetic features of ceramic artworks, to provide understandings which would inform their research, whether for the purposes of literature or field reviews, or for developing ways of describing artistic outcomes from their own studio-based investigations.2 While much of the material reviewed alluded only to aesthetics in the vaguest of terms, more of a problem was the distraction created by unnecessary references to technical or organizational issues. Perhaps most problematic of all was the uncertainty regarding artists’ or makers’ artistic intentions or ambitions for their work, so that appropriate criteria could be applied in its review or evaluation. The exasperated tone of George Woodman, the painter husband of Betty Woodman, the internationally profiled ceramicist, when writing on a topic of which he is both familiar and well informed, speaks volumes:

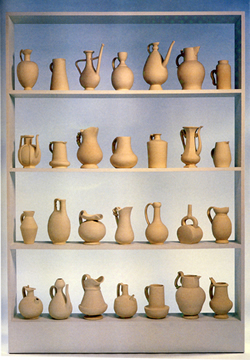

Although Woodman’s observations are made specifically in regard to colour, and published about a quarter of a century ago, the point he makes could equally be applied to many aspects of the discipline today. To illustrate this assertion it may be helpful to look more closely at examples of artworks made by a sculptor, as well as that of several ceramicists, all of whom make claims for responding in some ways to the location or the spaces in which the work is exhibited or placed. In the first instance, the work is written about by a third party, the second by an individual who is equally well known for his writing as for his ceramic work, and the last is a practitioner reviewing the work of another practitioner. First we look at the catalogue for Cecile Johnson Soliz’s exhibition, Regarding the Function of Objects, held at the National Museum of Wales, Art in Wales Gallery in 1999. Juliet Carey, the Museum’s Assistant Curator of Art, starts her introduction by describing key aesthetic features of Johnson Soliz’s works in terms of the impact they make on the viewer, describing the ‘pallor and luminosity of their ceramic surfaces’, making connections by drawing attention to ‘rhythms of shapes and intervening spaces’ which ‘have an austerity and integrity reminiscent of still lifes by Chardin and Morandi’ – important references for Johnson Soliz.4 Carey goes on to point out that ‘the lack of colour and uniform texture in each work is infinitely suggestive’ – alluding to the active and important roles of these features in aesthetic terms. In the final sentence of what is still her first paragraph, she further suggests that the sculptures have a quality of being both ‘the thing itself’ and a representation of absent objects – a reference to the social origins and function of the ‘objects’ mimicked.5 When Carey starts to specifically describe and discuss Twenty-eight Pitchers, she draws attention to references drawn by Soliz Johnson - ‘handles imitating rope, twine, ribbon or metal … body shapes referring to sack or gut, tree trunk, gourd or egg’. As she walks around the work, she describes first, the ways the ‘grid of shelves flattens the collection of objects into a plane’ and ‘the memory on one side informs the response to the other’ and by completing a circuit, she achieves ‘an experience in three dimensions’. She quotes Johnson Soliz’s assertion that the pieces ‘appear heavy, but you realise that you’re thinking they’re heavy and you have not even felt them’- once again, an important aesthetic feature.

When responding to Five Pitchers, an earlier work, Carey points to the group’s ‘disquieting anthropomorphic quality, like a family portrait’, before going on to describe the ways Johnson Soliz’s uses ‘wash drawings to help her define the shapes and spaces in her work’ and this in turn, informs ‘her manipulation of the shapeless clay’ – a useful insight into the artist’s ways of working for the reader. Carey goes on to describe Johnson Soliz's use of coiling to both conveniently construct her forms and to exploit the slight unevenness of the resulting profiles and surfaces, to subtly (and effectively) distinguish these depictions of vessels from the original more precisely manufactured artifacts referenced elsewhere in the Museum – a valuable reference to the ways material and process contribute to the aesthetic of the work. Mention is also made of the ways Johnson Soliz ‘always elevates her work to eye level so she can see the profile whilst making’, and that the low temperature of the firing of the piece is purposeful, in that it ‘opens the surface to light’. After reading Carey’s introduction, one is left with a very strong impression that that she had gone to considerable lengths to cover points which had been discussed in detail with Johnson Soliz, in terms of important aesthetic features of the work exhibited. These insights were in sharp contrast to those of James Roberts, in his review of Johnson Soliz’s Three Pitchers (a very similar work to Five Pitches) for Ceramic Review. Roberts starts with the term ‘Containers’! He continues by suggesting that ‘one type or another [containers], are the first experience we have of conceptualizing space’, before musing over the ways ‘museums catalogue civilization through its containers – some cultures are known only through their vessels’ before commenting on the ‘sense of an object that is at once familiar from memory, yet distanced through time and context’.6 For the remaining half of his article, Roberts first ponders on whether the pitchers are ‘improbable rejects … of some whim of human sensibility towards the function of pouring and filling’, and in the same sentence brings in the issue of ‘survival of the fittest even amongst domestic ceramics’. He goes on to identify a number of reasons why he believes the pieces would not ‘function as vessels’, including ‘their handmade nature’, the ‘atypical construction’ and the fact the low fired body would ‘soak up liquid like a sponge’ - the question arises at this point as to whether Roberts was writing about the same artist’s work as Carey?7 Now we look at something different in terms of location and purpose for the work, where Edmund de Waal explains in the exhibition catalogue for his ‘installations’ at Blackwell, the Arts and Crafts house in the Lake District, 2005, that he was ‘asked to work with the house, rather that just provide an exhibition of pots’.8 He fully and precisely describes his experiences in aesthetic terms, when visiting the house prior to the making, or perhaps more accurately, the selection of pieces in response to the temporal and ephemeral ‘shifting patterns of sun and shade’, exploited by the house’s architect.9 Almost half of de Waal’s introduction describes, elegantly and in detail, the ways he responded to various spaces and made or selected pieces for specific locations, noting the potential challenge of certain windows which ‘almost fiercely geometric … frame views over Windermere as if to challenge anyone to complete pictorially’.10

Having explained his response to the house in these detailed ways, de Waal nevertheless provides no self-evaluation of the ways the artworks aesthetically connected to, or interacted with, the spaces in which they were installed. Attention for example, could be drawn to the ways in which the vertical reflective surfaces of light-toned open cylindrical forms in A line in the sand appear to absorb the darker tones of the wooden window furniture on which they are placed. This creates a subtle transition of tone from light to dark, causing the relatively straight-sided vertical profile of the cylinder to become indistinct and ambiguous. Where the tones of the cylinder and the surface upon which they are placed converge in value, the ceramic work appears to be integrated or absorbed into the horizontal surface of the wooden window furniture, making also ambiguous, visual demarcation between fixed structure and temporary artwork. Perhaps another example, would be to describe the ways this installation would be experienced differently as the direction, colour and intensity of the sunlight shifts, as the day progresses – something with the potential to be exploited! In Tony Franks’ article for Ceramics and Perception on the ceramics of Clare Twomey, which is a review of the artists ‘installations’, Franks starts by explaining the term ‘installation’ using his own impression or interpretation,11 before quoting Glen R. Brown, a professor of art history: ‘while examples of ceramic installations are now abundant and variable, it may be observed that in all cases a particular condition of their being is their ambiguous situation along the boundary between the field of ceramics and contemporary art’.12 Unfortunately this quote doesn’t clarify the point! Elsewhere in his review, Franks describes his initial response to Twomey’s works in aesthetic terms – ‘one feels a disconcerting loneliness, like in a city street in the early hours of the morning, or a familiar room without its occupants’ - but without identifying a specific work which elicits this response.13 He is more specific when describing his experience of Shoal (1998) - ‘a group of more than 100 slipcast nuclear submarines suspended in cool blue light … swim seductively like exotic tropical fish - drawing the reader’s attention to ways the directions and qualities of lighting significantly contribute to the aesthetic experience of this work, initially lulling the viewer into a false sense of ease ‘until the realization of their true identity dawns and their soft enlarged shadows adopt a threatening role’.14 Nevertheless, it is suggested that an opportunity was missed by not also covering the ways in which the hues and tones of the surfaces (and whether these were matt or reflective) diminished or enhanced perception or experience as the viewer moved through the work. Having looked at these few examples, it has been a relatively easy task to point out some of the problems related to what may or may not be described or discussed in ceramics, or what may be given priority or precedence. Addressing the problem is far from straightforward, nevertheless it has been an important aspect of the research undertaken at Cardiff School of Art and Design, and a few helpful principles have emerged and have been tested over a number of projects. First, artistic aims or claims have been framed as research questions and clearly articulated. Secondly, aims or claims have been placed in context according to relevant theories, discourses and debates, which may or may not be directly related to ceramics. Thirdly, these theories have been examined for their implications for the projects, helping to identify the most relevant ways to describe, evaluate and discuss the aesthetic features of the artworks under investigation. Fourthly, material properties, practical or technical details are only included as footnotes except where their contribution to the aesthetic features of the work, can convincingly explained. Fifthly, the process of evaluation and the process of having to describe and write this down is key to the effectiveness of the research. So one could conclude that whilst ceramics and sculpture clearly do have much in terms of a shared aesthetic, many important but actually peripheral factors, appear to distract focus from the key element in artworks in ceramic (and all art) – their aesthetic features! This perceived situation also appears compounded by the paucity or inadequacy of description of these aesthetic features and little articulation and discussion of the factors or conditions, which contribute to creation of these aesthetic features. If this is a fair reflection of what happens in practice, it has major implications in terms of limiting the potentially artistic development of practitioners, and also the standing or status of the discipline An important step way of addressing the problem, is to acknowledge that there is a problem! Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes To return to the article click the relevant note number. 1 Jeffrey Jones, A Rough Equivalent: Sculpture and Pottery in the Post-War Period, catalogue for exhibition held at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 30 September 2010 – 2 January 2011, p.12. |

||||||||

What difference can a description make? • Issue 14 |