Interpreting Ceramics | issue 16 | 2015 Articles, Reviews & Reports |

|

|||||||||||||

Upcycling Stereotypes – Telling Stories of AfricaHelen Doherty |

|

|||||||||||||

|

The commercial success of Ardmore Ceramics, a collective studio in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa, is well documented, however, of greater interest is the polemical debate which it has drawn locally and amongst Anglophone audiences. South Africa has been spoken for – represented and translated – through Western and non-African eyes for so many centuries that these stereotypes still abound today and problematize attempts by native inhabitants to forge an authentic identity. One response which Ardmore artists explore is to upcycle this stereotype. Besides analysing criticism which Ardmore has attracted, this article investigates key moments in the trajectory of its history. I argue that there is a consistency between the actual mechanics of the studio and the tradition and philosophy which underlies the practice of these primarily Zulu artists, and it is this convergence which is pivotal to Ardmore’s success. Introduction Curiosity was the main inspiration for this article. Curiosity firstly, at a South African ceramic studio, Ardmore, which has had success internationally and at home (as reflected in auction prices and acquisitions), but also drawn extremely divergent opinions.1 Art which stirs such polemical debate merits, I believe, a closer look. Personal experience further piqued my interest: I visited the studio in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa in November 2013 and interviewed Fée Halsted, its co-founder. Another influencing factor is that I am, like Halsted, a white, South African woman who was educated in South African institutions which followed the British canon, and similarly, am attempting to regain a sense of being African through art.2 My perspective seeks to balance predominantly theoretical reviews of Ardmore, since it is informed by my being a practising ceramic and fine artist, educated in South African, Irish and Welsh universities. This article analyses the production and impact of the ceramic narratives created by Ardmore artists, in particular those which address stereotypes and effectively transcend or upcycle them. Telling stories of South Africa

Much notable art is made so by a captivating story – told through form, imagery, text - or appended to the artwork - such as details pertaining to its production (for example, unexpected alliances). In the case of Ardmore Ceramic studio, situated in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa, the narrative appeal operates both within the artwork, which tells a variety of tales – whimsical, cautionary, historical – and in the studio’s history.5 Besides investment value and aesthetic appeal therefore, the lure of a conversation piece remains singularly attractive. This is possibly because, as the proliferation of social media websites and apps attest, contemporary society (contrary to Barthes’ earlier estimation) is engrossed in storytelling: we spend hours every day tweeting and WhatsApping news. However, our appetite for tales told through art, as Fée Halsted observes above, is critically influenced by geographical location and content.

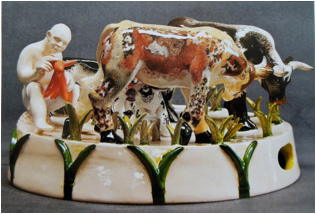

The success of Ardmore, founded in 1985 by Halsted and Bonnie Ntshalintshali, is tied to these factors. Besides the fact that the work reflects Africa as seen through the eyes of African artists in situ, it also grapples with pertinent, current issues such as the problems of mass migration and xenophobia. These stories about Africa which Ardmore artists have been telling for the past thirty years all began with one woman’s determination to forge her South African identity; her self-discovery thus took place in tandem with theirs. In the beginning: asking questions It all started with a question: what does it mean to be a South African living in apartheid South Africa in the 1980s? And, more to the point: how can I – a white, female artist – bear witness to my time? This was the question Halsted put to herself in 1982 at a time when her student contemporaries, she recalls in her book, Ardmore: We Are Because of Others (2012), were still living very much in England’s shadow, emulating the functional, studio pottery style of Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada.6 As a ceramic student in the early 1980s at Durban Technikon in Natal, Halsted caught the attention of visiting American ceramist, David Middlebrook, precisely because her work resisted this trend. She grappled instead with expressing her South African identity and, drawing on her background in Fine Art, determined on ‘taking ceramics from craft into the realm of fine art.’7 Then she did two extraordinary things which, twenty-five years on, contributed to her being honoured by the Women’s Campaign International in Philadelphia, USA (former recipients of which include Hilary Clinton).8 Firstly, she set up a ceramic studio in the Drakensburg, Kwazulu-Natal with Bonnie Ntshalintshali, a Zulu woman, the daughter of her family’s housekeeper, whose polio had made her unfit for farm work.9 Secondly, she decided to employ and teach only local, Zulu women in the studio.10 Since gender equality was barely a whisper on the wind and employment equity unheard of in the 1990’s – South Africa passed the Employment Equity Act in 1998 – this was a bold move reflecting Halsted’s tenacity and foresight, qualities which have underpinned Ardmore’s success.11 Working together Currently, Ardmore is lauded in South African media as ‘a national treasure’ and an ‘iconic South African ceramics brand,’ which South Africa’s VISI magazine credits with ‘setting the standard for ceramics.’12 Certainly in November 2013, while I was standing in the Bonnie Ntshalintshali museum, which is the main room of the gallery at Ardmore and showcases the eclectic range of work produced by the artists since its inception, I found it easy to see how it is one of the most successful ceramic collectives in South Africa.13 What was not easy to understand nor immediately evident, is how Ardmore has reached this point and how the criticism it has received can be reconciled with the studio’s achievements. In order to shed light on its current position, I would like to go back to Ardmore’s past and inception. Initially, South Africans were cautious about buying Ardmore ceramics and the studio’s journey from its humble beginnings to current success, is well-documented in Halsted’s book, Ardmore: We Are Because of Others (2012). An understanding of the context in which these artists first began to construct a South African identity, may shed light on their story. Firstly, Halsted must have been aware that the women she was employing in the early 1980s – 1990s, having grown up in rural Kwazulu-Natal, were geographically isolated with minimal formal education and little exposure to European culture. However, the environment and culture to which these artists were accustomed provided provided a rich source for the stories, forms and ideas expressed in their work. Broadly speaking, South African flora and fauna, Zulu customs and traditions, Christian parables and personal stories formed the content, and Halsted encouraged this choice but also guided them to expand. For some the work was an extension of skills their parents had taught them as children when they would fashion and sell clay animals to tourists. Nhlanhla Nsundwane’s sculpture of a young herdsman keeping an eye on his cattle whilst modelling a clay form is a retrospective piece which enables the artist to assess his present identity through re-presenting the past.

As Ardmore grew and the artists built up knowledge of the market, its profile changed. Men are employed now as well as women, Africans other than Zulus. But Ardmore has maintained its appeal to Anglophone audiences partly because the work is still made primarily by local, Zulu artists in a remote location in the South African countryside.14 Authenticity, according to Walter Benjamin, depends on ‘cultural distance over space and time from one social situation to another.’15 Halsted’s active position as mentor-manager-owner within Ardmore could dilute this authenticity given her broad knowledge of other ceramic styles and understanding of the international art market, both factors which influence how she teaches and guides the artists’ making styles and choice of themes. Jo Dahn’s account of Ardmore’s participation, represented by Wonderboy Nxumalo and Halsted, in the International Ceramics Festival in Aberystwyth, 2001, reveals some issues which a largely European audience had with Halsted’s roles in Ardmore. Initially Halsted’s protective attitude, Dahn reports, caused controversy, especially the fact that she seemed to be speaking for the artists. To ‘the self-consciously liberal audience,’ the scenario mirrored too closely the power structures of apartheid.16 But Halsted redeemed herself later by explaining, ‘If I offend in any way,’ it is first necessary to understand ‘the poverty… the situation in South Africa,’ where unemployment and illiteracy are rife, reliable forms of income, rare.17 Similarly Chris Thurman hones in on this issue in his article for South Africa’s Business Day in October 2012, maintaining that Halsted is ‘potentially patronising.’18 What challenges these estimations is the collective weight of the facts that firstly, Halsted is an artist herself who established Ardmore as a collective, and is constantly learning, teaching and expanding with the artists. The studio is run on Ubuntu principles of equality and collective responsibility (to be discussed later). Secondly, her fluency in Zulu facilitates equality and encourages open communication with the artists which is particularly important in a country where much of the white population cannot speak the regional, African language.19 Thirdly, the corpus of knowledge of the Zulu culture which Halsted has built up over the forty-plus years she has lived in Kwazulu-Natal, plus the educational and health facilities which the studio provides, reflects a respect and genuine concern which does not connate to a patronising position.

The essential point Thurman has overlooked here is that an artist’s top priority and identity, lies in making art. Having the time and facilities to create is of inestimable value to a ceramicist who cannot set up practice (with a kiln, glaze room and extraction), as easily as a painter, for example. It is also critical in the context of South Africa, where ceramics as a discrete subject is no longer taught at third-level educational institutions (reflecting a world-wide trend). Further, the remoteness of Ardmore’s location meant local people would have been unable to develop their talents had it not been for Halsted. Ardmore’s success is a great inspiration for aspiring artists and those who work at the studio are known as the ‘isigiwili,’ which in Zulu means ‘those of good fortune.’20 At an Ardmore exhibition at the Charles Greig Gallery in Cape Town in 2012, Halsted explained: ‘It’s a way of showing people with little hope that you can start something out of nothing by using your hands.21 As Lovemore Sithole, a Zimbabwean refugee and thrower, summarises it: ‘Fee has given me freedom.’22 Petros Gumbi, a sculptor and Punch Shabalala, a painter, attest that Ardmore has given them the opportunity to develop their talents, mentor other artists and educate their own children.23 It is hard to overstress Ardmore’s role in social upliftment situated as it is in rural Kwazulu-Natal, an area which is ‘poverty-stricken … rife with AIDS, poor living conditions and unemployment.’24 The growth of SMEs, Ingrid Stevens observes in a recent article on Ardmore, offers a viable solution.25 Subject matters Although Halsted initially eschewed the Anglophone style of her art college contemporaries in her search for an authentic South African identity, she did not hesitate to expand the awareness of the Zulu women who started at Ardmore in the 1980’s. Thus, whilst recognising their natural flair for design, colour and rhythm, Halsted taught them an organic style of making and showed them European styles and ceramic forms for inspiration. The resulting work, as Moira Vincentelli puts it, ‘epitomises the hybrid culture of contemporary South Africa.’26 Themes have expanded to address issues which impact the culture and also personally affect the artists. Integrating these concerns as narratives within the work illustrated through sculptural forms, imagery and text, these pieces serve a quasi-didactic purpose. Wonderboy Nxumalo’s series of plates warning of the dangers of AIDS is a poignant example of such narratives. One of Ardmore’s foremost artists, Nxumalo himself died of AIDS and our knowledge of his history gives the work particular resonance. This series, made between 2000 to 2008 was especially important in a community where illiteracy and the HIV infection rate were very high, since pictures could reach a wider audience. Narrative of the Land Some of Ardmore’s ceramic narratives reflect a romantic image of Africa and when I raised this issue with Halsted during our interview, she admitted that Ardmore does tap into an idealised South African portrait. Yes, it does embody the mesmerising rhythm of a primarily rural Africa in its flamboyance, brilliant colours and modelled fauna and flora. In this sense, Ardmore is not innovative, but it is also not inauthentic, since the subject matter reflects a real environment: the studio is located in an area of great, natural beauty: amongst the rolling hills on the picturesque Midlands Meander near Howick. That this is the physical environment in which Ardmore artists live and create, goes a long way to explaining the organic shapes, gorgeous colours and spirit of abundance reflected in the work (for Ardmore is nothing if not a celebration of South Africa’s natural beauty).27 However, many South African citizens are disinclined to buy such seemingly simplified portrayals of their country, wise as they may be to its real complexities. Yet these idealised portrayals are ultimately lures, for closer inspection reveals a sophistication of technique, complexity of narrative and realistic depiction of contemporary issues the collective impact of which is to disallow merely superficial readings. Sometimes with challenging narratives therefore, a ceramic’s functionality is a decoy. ‘Platter’ or ‘candlestick’ are mere labels or semiotic comfort blankets designed to still a buyer’s nervousness when contemplating objects whose impact or meaning, she or he suspects, exceeds their nominated use.

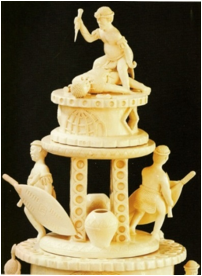

Another salient factor influencing subject matter and style is the historical importance of Ardmore’s location, for the landscape is steeped in history. A short distance from the studio is the Mandela Capture Monument which commemorates the exact spot of Nelson Mandela’s arrest before his 27-year-long imprisonment.28 In addition, the mud huts of labourers which interrupt vast tracts of farmland bespeak a land of inequality which also has a protracted history of resistance to colonial rule as well as civil war.29 Some artists explore their current identities by reflecting on their past in ceramic historical narratives. A case in point is Petros Gumbi’s sculpture, The Murder of Shaka. This dramatic, complex sculpture of the fall of a legendary Zulu king is clear-glazed and unpainted, which lends a sombre tone to the subject matter. In the fashion of early Staffordshire flatbacks, it is a memorial piece.

Narrating Africa- Upcycling and Exploding Stereotypes Before turning to Ardmore’s ceramic narratives and their impact on readings of an authentic South African identity, it would be expedient to consider earlier historical accounts of Africa. Stereotypes of Africa are rooted in the records which travelling artists, such as Thomas Baines (1820-1875) and William Cornwallis Harris (1807-1848), made during colonial times. Their detailed drawings and paintings of South African tribal customs, wild animals and landscapes were exhibited in the metropolis and Europe, and received much like photographs were until recently – as faithful records of these exotic lands. As Jan Nederveen Pieterse puts it: ‘What Africa did have and in abundance, also according to Europeans, was nature,’ and ‘the kind of wild and overwhelming landscapes which make human beings seem small.’30 Drip-fed by tourist brochures and travel documentaries, such as Ewan McGregor’s and Charley Boorman’s Long Way Down (2007), this romantic perception persists today and has problematized an African’s view of Africa. Consequently, when an African interprets or holds up a mirror to her own country, the result can seem clichéd – implausible or suspect, even to fellow citizens. As such then, Ardmore foregrounds an issue which all ex-colonies, and to a degree, all artists, need to confront: how to forge an authentic identity and situate your art within the global arena, yet avoid being overly influenced by your former colonizer or predecessors. At the crux of the matter is the fact that the South African identity was ‘colonised’– typified and formalised by primarily European authors (tradesmen, explorers and missionaries)for mainly non-African audiences. This expropriation has problematized their subsequent attempts to become authors of their own identity. This struggle to locate a genuine post-colonial identity (as distinct from the colonial interpretation), is also compounded by what Franz Fanon identifies as ‘decerebralization’: a process during colonisation in which the native people experience self-estrangement, and become alienated from their own culture, language and land.31 I would like to draw out some aspects of this issue next to demonstrate some of the complexities involved in the construction of a South African identity. Firstly, it is important to note the similarities between early, colonial records of the South African ‘identity’ – which include visual and written records of its fauna, flora and diverse cultures – and contemporary accounts provided by native inhabitants at Ardmore. In short, the South Africa which early explorers recorded is still partially extant: the rich variety of wild life and traditional cultural practices of some ethnic groups.32 However, what is new, and it is inflected in Ardmore art to create a fundamentally different picture, is the mind-set through which this experience of living in South Africa is filtered. Ardmore ceramics are informed by artists mostly living in strong-knit, rural communities who still practice traditional, Zulu customs. This is a far cry from the surface impressions of itinerant European explorers who were merely passing through Africa, or temporarily based there. Moreover, Ardmore artists’ depiction of Africa is directly influenced by their being rooted in the country, by real, lived experiences. However, this sense of belonging to South Africa is not one which all races share equally, which is where Halsted’s role in Ardmore and her attempt to forge an identity becomes interesting. As the writer, J.M. Coetzee points out, the unease and guilt which white South Africans feel at being associated, by virtue of their colour, with the apartheid regime, has disallowed many to feel at home there.33 Despite being raised in South Africa, I felt more attuned to Anglophone culture due to a British education system, which partly explains my initial impression of Ardmore as unconvincing – they seemed prosaic and idealised – as I compared them to what I had been taught were superior ceramic styles (British, European, Eastern). Identifying more readily with the colonising culture is a common reaction among immigrants in ex-British colonies. Reared on a diet of British literature and art (through the education system), they see their own country through a foreign filter and experience the schizophrenia of a mental landscape of green hills and daffodils, whilst physically inhabiting a country of dust and drought. The resulting sense of dislocation Heidegger termed umheimlich – literally unhousedness or ‘not-at-home-ness.’34 Marcus Clark, a nineteenth century Australian writer comments on the ‘uncanny nature’ of the Australian landscape;35 and my childhood stories were imports: Aesop’s fables and Rudyard Kipling.36 Text, as Chris Tiffin and Alan Lawson observe in De-Scribing Empire: Post-colonialism and Textuality, is a powerful tool of colonisation which reinforces power structures, because ‘when the children of the colonies read these texts, they internalise their own subjection… the work of colonial textuality is done.’37 South Africa has been spoken for – drawn and translated through primarily Western or non-African eyes – for many centuries, and it is only comparatively recently that South Africans, both white and black, have started to reclaim authorship of their own image. If we are slow to recognise the authenticity of their versions, perhaps it is because we are out of practice. It has taken me ten years of living abroad to appreciate the truth in the stereotype: that South Africa is different from other Anglophone countries.38 Ardmore both celebrates and shares this difference. In short, it has upcycled the stereotype. The Ceramic Narratives Ardmore, in its treatment of narratives which epitomise South Africa, inevitably challenges some illusions about the country. Since stereotypes, as Pieterse observes, ‘form the psychological and cultural furniture of society’s mainstream, ’their critique is tantamount to undermining this ‘mainstream.’39 Playing on archetypes of Africa, Ardmore ceramics draw the audience in so as to suggest more complex readings. For example, at first glance the Riders series made in 2011, is a charming depiction of Zulu people travelling on a variety of wild animals. Yet small details within the work hint at a darker side to this apparently innocent parade. A case in point is a hippo riders’ vase, sculpted by Alex Sibanda and painted by Jabu Nene. Aesthetically, the vase is pleasing – the form is harmonious, the surface beautifully painted. But whilst the rim of the vase supports riders triumphantly astride hippos, its side and base depict a more sinister version of the hippos: as swallowing some of the riders. The exhibition’s objective was to highlight the suffering of Zimbabwean refugees who have fled their country in recent years and the depiction of wild animals for transport suggests the riders’ powerlessness and lack of resources. An awareness of the exhibition’s title – and therefore the story and context of these ceramics – irrevocably changes and deepens our initial reading.40

Another stereotype which Ardmore challenges is of Africa’s AIDS crisis. AIDS is still widespread in South Africa, yet the artists’ responses to it reflect a high level of personal commitment, bravery and communal effort. In the 1990’s KwaZulu-Natal had the highest rate of HIV infection and mortality in South Africa partly due to cultural taboos, lack of education and poor diet. In 2011, the mortality rate was still high (37.4%), the area the worst affected in the country.41 Halsted’s direct involvement in tackling this epidemic in the face of the South African government’s apathy, which claimed the lives of many of Ardmore’s artists, including its co-founder Bonnie Ntshalintshali, has been extensively documented and therefore will not be discussed again here.42 However, what has perhaps not been sufficiently extrapolated or investigated is the range of artists’ response to this epidemic (possibly inspired by Halsted’s example).

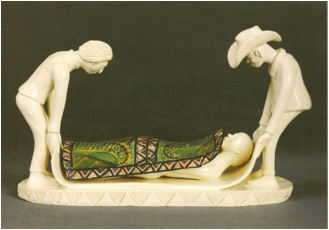

A case in point is Petros Gambi‘s sculpture of Mother’s Lament (2009), which effectively humanises the epidemic, in portraying the real consequences of this disease on loved ones. The collective suffering of these women who have lost children to AIDS, is conveyed in the sombre mood of this clear-glazed, unpainted piece, their solidarity is underlined by its circular construct. Similarly, the vase sculpted by Sfiso Mvelase and painted by Mavis Shabalala, which depicts the AIDS virus as a baboon wreaking havoc, uses a language which the local community and a wider Western audience can understand – of archetypal, mortal dangers. Sadly, some of Ardmore’s most successful artists made their best work whilst suffering from AIDS. WonderboyNxumalo (1975-2008) is a case in point, and as such his work brings to mind Gilles Deleuze’s description of an artist as someone who has ‘seen something in life that is too much for anyone, too much for themselves,’ and which they are nevertheless compelled to express.43

After six years of treatment with ARVs and Ardmore’s support, Shabalala recovered sufficiently to be able to paint the blanket covering her body in the sculpture. In this case, the ceramic could be seen to have an apotropaic function: Punch’s recovery was a direct result of the loving care of her community as presaged by and depicted in this sculpture. The greatest obstacle in tackling AIDS amongst her local community, Halsted recalls, is the Zulu belief that it is ‘a tagati, an evil spell cast on a person’, as this precludes discussion of the issue as ’disrespectful’ of the ancestors.44 Since her recovery therefore, Shabalala has undertaken to actively educate her community about AIDS and gives talks to spread awareness of prevention and care.

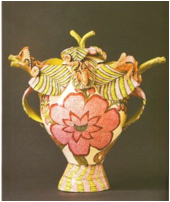

Out of Africa: Wildlife Stories Abound The abundance of wildlife in Africa has always featured in explorers’ accounts and today this illusion persists. However, the depletion of stock through trophy hunting and poaching is an ongoing problem which Ardmore has highlighted through several initiatives. Through sales and auctions, the studio has supported rhino conservation, raised funds for World Wildlife anti-poaching and staged a Travellers of Africa exhibition in Johannesburg to raise awareness about African wildlife.45 In Halsted’s words, passively sitting on the fence in South Africa, is not an option. For this reason and because she is genuinely responsible in the denotative meaning of the word – taking action when her principles are under threat – Halsted has insured that Ardmore promotes projects which reflect the ubuntu spirit that all life is interlinked. Ardmore demonstrates a collective spirit and responsibility for the environment and community which is inspiring in an age where the sheer volume of tragedies reported daily in the media can be overwhelming. Since the Ardmore gallery is included in the provincial syllabus for local Kwazulu-Natal schools, the younger generation are informed of these concerns.46 Critical to the success of Ardmore’s campaigns is its prestigious reputation as this ensures that it reaches a clientele empowered to make changes. Similarly, Josiah Wedgwood’s medallions issued in the late 18th century (1787) to campaign for the abolition of slave trade, targeted a clientele which included the elite, ruling party.47 A recent exhibition in February 2014, The Great Herds of Africa held in Constantia, South Africa, highlighted the problems of illegal and indiscriminate hunting practices. The art was a tribute to three hundred elephants poisoned for their tusks which, to quote Halsted, ‘invokes memories of ancient ivory carvings that now shame us into action.’48 Far from allowing viewers to passively enjoy the beautiful ceramics, this exhibition was intended to be reactionary and a clear case for future intervention was highlighted: excessive eland hunting in the Drakensberg is threatening the species’ survival.49 Ubuntu: The Philosophy Behind Ardmore The Story Behind Production Despite the team effort which goes into the ceramics, individual recognition is given to each artist, who signs the piece she or he made and is remunerated accordingly. Furthermore, the artists occasionally travel with their work to international exhibitions and enjoy recognition as the makers. During the Industrial Revolution, division of labour in ceramic factories meant only notable modellers and painters received recognition both in monetary terms and reputation – they signed their ceramics.53 Today, despite the efforts of high profile celebrity artists, such as Ai Weiwei and Grayson Perry, and the growth of television programmes, namely BBC2’s show, Paul Martin’s Handmade Revolution (October 2012), to promote ceramics, the art/craft hierarchy seems firmly entrenched as many contemporary artists will outsource a craftsperson, yet seldom cite their contribution: for example, Fred Wilson, Barbara Bloom and Jan Fabre.54 Since the material is invariably mentioned on the work’s title, the actual makers are accorded a position of lesser importance than the processes and inert matter that constitute the artwork.55 However, given the revival of interest in the hand-made and its association with authenticity within the context of a fully mechanised, industrialised, Western society – what Brian Spooner terms ‘the resingularization of commodities in Western society’ – Ardmore’s success is actually rooted in the ongoing production of traditionally hand-crafted, unique pieces.56 Painting patterns Besides in subject matter and production, Ardmore ceramics stand out as distinctly African by virtue of some of the artists’ painting styles. Glory be to God for dappled things – Gerard Manley Hopkins’ hymn to many-patterned things of English soil (Pied Beauty, 1877), could just as easily apply to South Africa if some Ardmore artists’ styles of decorating every surface with networks of repeated patterns is anything to go by. African rhythm (complex and insistent), and the wide variety of flora and fauna is the basis of Ardmore’s subject matter – hence this obsessive filling in.58 Furthermore the patterns on these ceramics, as Halsted explained to me, are distinctly African, drawn from Zulu mythology. One recurring pattern is the Amasompa. A node with a raised surface, it represents the egg as the origin of life. A feature of traditional Zulu pottery and beadwork in the form of circles and dots, the Amasompa is often paired with the Chevron, a zigzag pattern, its masculine counterpart. The work of the painter, Jabu Nene, beautifully balanced and decorative, exemplifies these Zulu features. This Chameleon urn, sculpted by Somandia Ntshalintshali and painted by Jabu Nene in 2007, illustrates her style.

Ardmore’s Reception within the South African Market: As ‘one of South Africa’s greatest design success stories,’ Ardmore may be synonymous with high-end collectibles owned by celebrities and heads of states, yet whilst non-Africans showed an early interest, South Africans were more wary.59 Halsted attributes their caution to poor art education coupled with a lack of confidence in art not yet appraised by the international market.60 The way I see it, Ardmore is both simpler – it does delight unapologetically in what distinguishes South African culture and wildlife from the rest of the world – yet also more complex. The work makes a valuable contribution to post-colonial debate by portraying local stories as well as re-telling historical incidents from the ‘Other’s’ perspective.61 It also consistently highlights current issues involving collective responsibility towards the environment and community and historically, in terms of its employment history, represents an exceptionally progressive approach during apartheid South Africa. In this sense, the work coincides with what Garth Clark (and Philip Rawson) identify as the function of a ceramic form: to produce meaning not just in an ‘internal, physical way,’ but, more importantly, to ‘extend out into the everyday, the social, the ethical … the broader sphere of human needs,’ and thereby, as Philip Rawson claims, to bridge the gap between art and life.62 Several factors have increased buyers’ confidence in Ardmore over the years. Initially, the large number of artists producing at the collective studio understandably made for client uncertainty. To reassure the market of each piece’s pedigree, Halsted devised a quality-control system: each ceramic which passes examination is stamped with the Ardmore triple A mark. Ardmore’s escalating success in international exhibitions and biennales, such as Korea and Istanbul in 2011, coupled with the fact that institutions such as MAD (New York Museum of Art and Design) and the Museum of Culture in Basel, Switzerland have collected their art, has further reassured the market. Recently, Christies of London gave investors their blessing by describing Ardmore as ‘modern collectibles.’63 Ardmore’s status was further consolidated when a vase by the late Wonderboy Nxumalo fetched over R200 000 at an auction in Johannesburg, the highest price at the time paid for a ceramic.64 Even the New York Times in March 2014, praised Ardmore ceramics as magical, ‘gravity-defying’ works of art: ‘rude, loud’ and ‘impossible to ignore.’65 Another factor which could account for Ardmore’s growing success is the cultural erosion which the EU and the UK are currently experiencing to which they are responding by literally investing and vicariously participating in foreign cultures: collecting cultural artefacts. Brian Spooner makes an interesting observation in his article, ‘Weavers and dealers: authenticity and oriental carpets‘(1986) – that we tend to associate authenticity with economically dependent societies.’66 Authenticity, Spooner explains, ‘is elusive because it is projected not only outside ourselves, but outside our social selves, outside our society…’67 It is therefore ‘a product of interaction between us (dominant) and them (dependent) and becomes more important as the gap grows…’68 When the first notable European artist of the early 20th century drew on African sculpture with an eye to re-vitalising his style, Picasso alerted the West to the regenerative potential of this relatively economically undeveloped continent. But Ardmore is striking for its very clear re-assertion of authorship and national identity: South African artists are shaping stories of how they see Africa from within the country. While the formation of the EU has encouraged collective identity and to this end, has really dissolved physical borders between countries, one fall-out has been a homogenising, flattening effect, which globalisation and neo-liberal agendas have exacerbated. As a result, these self-same countries have recently begun recognising the importance of ‘home-grown’ cultures and are taking steps to restore local identity. The rise of ultra conservative movements, for example, the BNP, reflects the spread of this idea in a less benign form; whilst individuals such as Billy Bragg, highlight more positive aspects. In an essay discussing the issue of identity, Bragg accedes that whilst Britons are ‘internationalist’, the issue of ‘local and national identity’ is equally important and therefore needs discussion.69 In the midst of such identity crises, non-African countries could take heart from indigenous peoples, such as the Australian Aborigines and the Zulus, who preserve their traditions through their art yet remain flexible: incorporating and addressing contemporary issues. To own an Ardmore ceramic therefore, provides a glimpse into a microcosm of a culture whose customs, Halsted assures me, are still practised in rural Zululand. Consequently, tradition emerges as valuable not only in itself, as a living archive of a people, but also, through the medium of art, as a means of actual survival. In conclusion, Bernard Palissy would have been enchanted, Adolf Loos appalled and Christie’s London is delighted at Ardmore’s ceramic range. Natural, realistic, expressionistic, didactic – trying to pin down Ardmore’s style is about as easy as defining existence itself. This is partly a reflection of its large volume of artists; partly because themes are directed by the exhibitions they regularly enter and partly because Ardmore appropriates, chameleon-like, European ceramic traditions and painting styles: the Bonnie Ntshalintshali museum provides abundant evidence of this hybridity and eclecticism.70 Perhaps a more useful exercise would be to describe what Ardmore isn’t: overtly preoccupied with emulating British or European styles (though it does borrow from them), also, little of the irony which characterises some contemporary art, is evident. Instead, Ardmore proudly finds its subject matter right under its nose – in stories of South Africa, which, although drawn from local narratives, nevertheless reflect on constants of the human condition. Being rooted in a local context, yet boldly drawing on other, non-African influences, gives Ardmore both the integrity and broad appeal to many tastes which is pivotal to its success. My lasting impression on visiting the studio was that Ardmore’s appeal and longevity lies in the whole story: its history and the artists’ collective effort. People do not buy Ardmore for its explicit or implied narratives, its gorgeous colours or exotic appeal only. Instead, they buy into the Ardmore ethic because they can relate to the bigger picture and want to become part of that narrative. Unbeknownst to them perhaps, they want to experience what it is like to be part of a wider community, to embrace ubuntu.71 Acknowledgements: With special thanks to Jeffrey Jones, Jo Dahn and Moira Vincentelli for their generous support and guidance. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 1 To date, Ardmore’s success and that of many of its individual artists, both at home and abroad, seems undeniable – if one takes into account the numerous media articles, record-breaking sales figures and exhibition attendance figures. Sotheby’s and Christies regularly auction the work, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York (MAD) owns pieces. Ardmore also holds the record for the highest price ever paid for South African ceramics. Information regarding the highest price sourced from Ingrid Stevens, ‘Art and Nature: Ardmore Ceramics South Africa’, Ceramics: Art and Perception, No 88, 2012, pp.78-81, footnote 2. 2 Whilst I am aware that several critics refer to Fée Halsted by her married name – Fée Halsted-Berning – I use the name which she chose in 2012 to cite authorship of her book, Ardmore: We are Because of Others, Cape Town,.Random House Struik. 3 Roland Barthes, The Pleasures of the Text (1990), 1973, p.47. 4 Hilary Prendini Toffoli, ‘Wonderboy Works Wonders’, South Africa’s Mail and Guardian, 16 May, 2014. 5 Halsted’s book traces the journey of Ardmore’s struggle, resilience and success in the face of great odds. 6 Halsted, Ardmore, p.33. This pathological rejection of their own country represents the triumph of colonialism which had supplanted the physical country with an imaginary Empire. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid, p.197. 9 Recognition of the innovative and creative nature of their collaboration came in 1989, when Bonnie and Fee were jointly awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist Award, never before awarded to a ceramist or a collaborative effort. Halsted, Ardmore, p.33. 10 In addition to this, she has focussed on empowering Zulu women (makers) who often struggle more than the men to secure a reliable income, as Jo Dahn reports. For example, she encourages them to open their own bank accounts in this way attaining ‘a modicum of independence in what is still a repressively traditional hierarchy’. Jo Dahn, ‘International Ceramics Festival, Aberystwyth, 2001’ Ceramics Monthly, vol.49, no.9, 2001, p.4. 11 Halsted has maintained this tradition of empowering women since the current ratio of woman to men artists is nearly double, and the women are equally successful. Information obtained from email correspondence with Jonathan Berning. 12 In South Africa’s Sunday Times, March 2012, Ardmore is defined as ‘nothing less than a national treasure.’ 13 Ardmore receives numerous requests from aspiring artists to join the studios monthly. 14 Walter Benjamin, as cited in Brian Spooner, ‘Weavers and Dealers: Authenticity and Oriental Carpets’ in Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2013 (1986), p.222. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 18 Chris Thurman as cited in South Africa’s Business Day, October 2012. The issue of Halsted’s race is also cited here: Thurman indicts her for replicating the traditional racial hierarchy in South Africa. To play the race card too, I would like to point out that a comparable ceramic studio run by a black South African does not yet exist in South Africa. Perhaps then, Halsted’s whiteness and patronage can be accepted as necessary evils without which such a studio would never have existed in the first place. 19 Many rural Africans equally have an elementary level of English, a situation which makes clear communication very difficult. 20 Halsted, Ardmore, p.8. 21 Halsted as quoted in South Africa’s Country Life magazine, 2011. 22 Halsted, Ardmore, p.8. 23 Ibid. 24 Stevens, ‘Art and Nature’, p.78. A case in point is Ardmore, which employs approximately one hundred staff and each employee supports ten family members. Annie Halsted, ‘Ardmore Ceramics ‘Out of Africa,’ Craft Arts International No 86, 2012, p101. 25 Ibid. 26 Moira Vincentelli, Women Potters: Transforming Traditions. Rutgers University Press, 2004, p.62. 27 Most of the Ardmore artists live locally and walk in to work every day as there are no bus services in this remote part of rural Natal. 28 This monument is an optical illusion created by Marco Cianfanell in 2012. It consists of 50 steel rods of varying lengths, which, when looked at from a certain angle, show the face of Nelson Mandela. 29 Initially, in the early 19th century, the Zulu chief Shaka, renowned for his ruthless treatment of intruders, kept all European settlers out of the interior (now Howick). However, in 1838 the Afrikaner Voortrekkers defeated the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River and established the Republic of Natal. A short-lived Boer republic from 1839 to 1843, the territory was then annexed by Britain. Information accessed on 30/11/2014 from website http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KwaZulu-Natal 30 Jan Nederveen Pieterse, White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture, Yale, 1992 (1990), p.35. 31 Franz Fanon as cited in, Robert C. Young, Post Colonialism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP: Oxford University Press, 2003, p.17. 32 In game lodges, such as The Addo Elephant Park in the Eastern Cape, and the Kruger National Park in the Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, most of the wild animals which the early explorers documented are still alive. In addition, initiation rites such as the Xhosa practice in the Eastern Cape, and the Zulu in Kwazulu-Natal, still continue today. 33 As Coetzee notes, ‘My passionate denunciation of South African tyranny stems from the fact that I am implicated (historically and emotionally), in the tyranny of South Africa and cannot disown that implication.’ Coetzee as cited in Alan Lawson, and Chris Tiffin, (eds), De-Scribing Empire- Post-colonialism and Textuality, London, Routledge,1994, p.90. 34 Heidegger as cited in Ken Arnold and Peto Jame, (eds), Identity and Identification, London, Black Dog Publishing, 2009, p.9. 35 Andrew Jones (ed), Dictionary of Globalisation, London, Polity, 2006, pp.65-66. 36 These stories helped colonial emigrants and British citizens in England to decode a foreign land. Yet no comparable bank of African stories exists in my childhood memory. This absence could be due to the oral tradition of storytelling in South Africa and the hegemony of English culture. 37 Lawson and Tiffin (eds), De-Scribing Empire- Post-colonialism and Textuality. Pp.2-4. 38 While South Africa has commonality with other Anglophone countries, it retains elements which are unique to it and perhaps reflect its turbulent history. The tendency to retain a sense of humour in desperate situations, to express a strong communal spirit and to be tolerant of difference (given the large number of ethnic groups), broadly defines a typical South African mentality. 39 Pieterse, White on Black, p.12. 40 Halsted, Ardmore, p.122. 41 Information sourced on 01/12/2014 from website: http://www.avert.org/south-africa-hiv-aids-statistics.htm 42 See Halsted, Ardmore, pp85-9. 43 Gilles Deleuze as cited in Damian Sutton and David Martin Jones, Deleuze Reframed, London, J.B. Tauris, 2008, p.65. 44 Halsted, Ardmore, p.97. 45 South Africa’s Witness magazine, July 2012, p.48. 46 The works also illustrate Biblical tales and post-colonial readings of history – the Zulu version of key events such as the 1878 battle of Isandlawana. Halsted, Ardmore, pp 102-3. 47 The medallion of the kneeling figure of a chained slave was accompanied by the words, ‘Am I not a brother, a man?’ Made in black basalt, it was distributed freely among Wedgwood’s clientele and is recognised for playing an important role in spreading awareness of the need to abolish slavery. 48 Extract from South African magazines, Weekend Witness, February, 2014 and Private Edition April, 2014, p45. 49 Ibid. 50 In terms of production, as an artist herself, familiar with the artistic temperament, this led Halsted to devise Ardmore’s flexi-time model. No regulated work hours, yet clear goals and exhibition deadlines, means the artists establish their own routines, which makes them self-employed and accountable 51 Halsted, Ardmore, p.5. 52 Halsted as cited in Toffoli, ‘Wonderboy Works Wonders’. 53 Johan Joachim Kandler, the chief model maker at Meissen and Ralph Wood, a model maker at Wedgwood, for example, both signed their original moulds and were remunerated for each one. 54 Michael Petry, The Art of Not Making: The new Artist/Artisan Relationship, London, Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp.25-29, and Glenn Adamson, ‘Goodbye to all That’, Crafts, Jan/Feb 2013, pp.38-39. 55 Halsted, Ardmore, p.86. 56 Spooner, ‘Weavers and Dealers’, p.220. 57 Stanza quoted from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem accessed on 13/12/14 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pied_Beauty 58 According to Halsted this rich, complex design has its roots in Zulu beadwork and basketwork. 59 South Africa’s Visi magazine, April 2012, p78, describes Ardmore ceramics, its textiles and soft furnishings range as ‘arguably one of South Africa’s greatest design success stories.’ 60 In 2004, when Christies of London, following a very successful auction of Ardmore ceramics, appraised them as ‘modern collectible’ their estimation publicly vindicated ‘overseas’ support and also reassured a nervous South African market. Halsted, F. 2012:p187. 61 Halsted, Ardmore, p.187. 62 Garth Clark and C. Strauss, (eds), Shifting Paradigms in Contemporary Ceramics: The Garth Clark and Mark del Vecchio Collection, Yale University Press, 2012, p.45. 63 Halsted, Ardmore, p.63. Of course, this estimation is in Christie’s best interest – to reassure the market of a safe investment, and therefore as such, cannot be taken as an objective, unbiased evaluation. 64 Ibid, p.185. 65 Extract from the New York Times, March 2014. 66 Spooner, ‘Weavers and Dealers’, p.228. 67 Ibid. 68 Ibid. 69 Billy Bragg as cited in Arnold and James (eds), Identity and Identification, p.54. 70 As we walked through this museum, Halsted pointed out ceramics reflecting the influence of the Expressionists, Italian Renaissance majolica, Staffordshire flat backs, Bernard Palissy and William Morris. 71 The practice of ubuntu, which underpins this collective spirit of the studio, is explained in a recent brochure available for all visitors to Ardmore Studios in Howick. I picked up a brochure when I went to Ardmore Studios in November 2013. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

||||||||||||||

Upcycling Stereotypes – Telling stories of Africa • Issue 16 |