Interpreting Ceramics | issue 12 | 2010

Articles & Reviews

|

Disciplined

Michael Jones McKean, Virginia Commonwealth University

(transcribed from the presentation given at the National Conference for Education in the Ceramic Arts, April 2009, Phoenix, Arizona)

| Contents | Home |

|

by Mary Drach McInnes The Convergence of Parallel Tangents by Timothy John Berg by Lawrence A. Bush by Rory MacDonald by Michael Jones McKean Interdisciplinary Mind, Deft Hand by Annabeth Rosen by Linda Sikora by Linda Sormin by Michael Tooby Modern British Potters and their Studios by Douglas Phillips A Guide to Collecting Studio Pottery by Juliet Armstrong by Leah McLaughlin by Alan Wallwork |

| NB. A Word document is available to download at the end of each article. |

Indisciplinarity and the spirit of collaboration are budding and alive within most of our universities. In our own classrooms many of us, in addition to the requisite Yanagi, Rawson and Greenhalgh feed our students a purposefully eclectic diet of String Theory, Flow Theory and Information Theory. We show them documentaries on free-diving and the Large Hadron Collider and YouTube videos on how to make a proper protest sign and PowerPoint presentations on the New Guinea Tree People followed with a clip of Werner Herzog lost in the jungle somewhere. We assign chapters from Marcuse, Sontag, and Calvino. And poems by Whitman and have them attend round table discussions on Armenian Diaspora. We listen to Albert Ayler and Lil Wayne, Bad Company and Beat Happening. And sustainability and memes, flower arrangement, kinesthesia, the short reemergence of Hammer pants, crowd sourcing, quietism and ontological space.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. What’s important in this list is not its weird specificity, but its breadth. In theory, by exposing our students to a wider array of information and sensibilities we’re granting them access to a larger, more peculiar world. One that is not so off-the-shelf. A world that is imperfect, but whole and wonderful. Through interdisciplinary studies and collaborative techniques we’re encouraging an ethos of tolerance and intellectual generosity. We’re fostering an ability to parse ‘meaning’ amidst an ever-increasing avalanche of ‘content’. Perhaps most importantly, this approach could help our students look at stuff without the crutch of a hegemonic eye; finding pleasure and meaning as easily in the quotidian as the preordained.

|

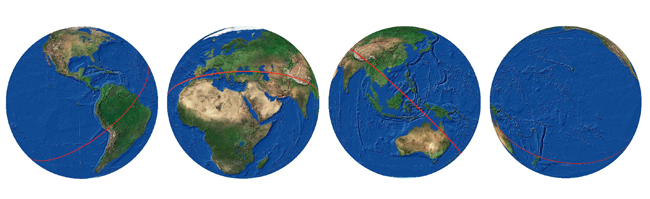

Fig 1. Michael Jones McKean, The Great Circuit, 2004-2006. The Great Circuit is the longest straight-line route around the earth as someone can take. The route takes into consideration the literally millions of minute shifts in elevation (elements encountered while actually traveling) to ultimately arrive at the longest path around the earth. The project began in 2004 as a conceptual query into changing and static limitations of physical and technical possibility. After two years of research I commissioned the University of Kansas Department of Geography and Cartography to build a computer program to sift and arrange billions of geographic data points. In late spring of 2006 the route was discovered. The project continues today in various forms. |

As with any worthwhile project, the benefits of this sort of training are as great as the potential pitfalls. While we continually re-tool our classrooms to echo a multi-disciplined universe we also risk producing thinkers content with simply honing their own brand of ‘intellectual whimsy’, a kind of self-aggrandizing intellectualism that roams and skips within the marginalia of culture. A breed of smarts that’s less critical than congratulatory outré, one that breeds excitement, but excitement purchased at the price of focused rigor and hard work. And as we rub our eyes from the drunken, hedonistic sleep of Pop and consumption, we blush in the awareness that the deft ‘naming’ of obscure pop-culture references has lost a bit of its witty tang. Sadly in this realization we find our students struggling to construct new content of their own. What remains are entrancements with style divorced from gestalt; a kind of affected nouveau-mannerism.

But through all this our desire for an art that is meaningful is not in doubt. Dan Graham once said: ‘all artists are alike. They dream of doing something that’s more social, more collaborative, and more real than art’. This is perhaps an earnest call for something more attached, more special and more profoundly connected to our lives as artists, and more generally, as people. There’s naturalness in longing for a practice that might engineer more meaningful social bonds, more intense and deeper feeling. But in Graham’s double edged statement lives an intentional irony; for as we almost unanimously desire interconnectedness in our lives, our quest to use our work to generate these real social relations inevitably runs us aground, beaching us against the limitations of our respective disciplines.

Yet, in our studios and classrooms stand fledgling attempts at reconciling with this inherently evolving vernacular language we collectively call art; a discipline that weare inheritors of and one that remains perpetually unfinished for us to continue re-imagining, demolishing or customizing as we please. In this spirit each of us, in some small way, are individual collaborators within this project. Through what we say and make, remember and consume, we’re agents responsible for its evolution and definition.

Subscription to this attitude about collaboration also brings with it a sensitive understanding of scale. As an example, we’re witnesses, and perhaps participants in the largest collaborative project in history: the sourcing and perpetual upkeep of enormous content management systems … think Wikipedia and YouTube. But unlike idealized representations of collaborative exchange this is happening quietly, remotely, and individually. Like many of our experiences a few months ago in a voting booth, we’re beginning to remember that our isolated behaviors and choices are never disconnected from consequences larger than ourselves. And with this, we’re witnessing a slow rewiring of our brains; a rewiring that embraces solidarity.

As the next generation of artists begins to make their way, they will be the first to consider the dualities between real and virtual, which by most measures is something quaint and left over from the 90s. The stage is set for interdisciplinary and collaborative exchange that no longer functions as a proxy for progressive pedagogy, but a basic requisite for citizenry. What’s more, collaborative exchange has the possibility to report back to us, telling us something particular and vital about ourselves in relation to our time. In this sense interdisciplinary collaboration has the ability to refocus our individual, sometimes anachronistic ambitions and optimize them into some kind of jangly unison.

|

Fig 2. Michael Jones McKean, Proposal for Certain Principles of Light and Shapes Between Forms, 2009 A small rainbow, about 80 feet wide and 30 feet tall arching over my studio building in Richmond, Virginia made using sunlight and water supplied by a series of pumps, hoses and nozzles. |

Nevertheless, as we continue to toll the virtuous bell of collaboration and spread interdisciplinarity like a salve across academe we should be careful, however noble our intentions, not to doom ourselves with nearsighted enthusiasm. We have, perhaps already, unwittingly established a hierarchical model that over-values the novelty of collaboration, participation and plurality, often purchased at the price of individual disciplines’ old school, hardscrabble specificity. As we check our zealousness at the door, many of us who strived to integrate plural approaches inside our curriculums are left wondering if we might have lost something important along the way. While striving to be liberated from the limitations of ‘medium’ we find ourselves inevitably conscripted to just another form of art’s unique dogma; still caged to invented realties of our own design. Interestingly, old-fashioned specificity is looking a bit roguish, relevant. As the scholarly material devoted to considering collaborative, relational and social practice compounds and universities rush to mint visual studies programs, the siren song of interdisciplinarity and collaboration is difficult to escape. More specifically, we are witness to the marketing of artwork that aggressively waves a collaborative banner, as if the mere assertion of collaboration automatically grants conceptual currency. In this way, we run the risk of performing our collaborations, carelessly thinking of our exchanges as the artifact or ‘end’ itself,rather than as a powerful ‘means’.

Inside our homes, inside our classrooms and inside our studios we are presented daily with the effects of transdisciplinarity, but we are also affected by it, profoundly. In his novel Molloy, Samuel Beckett wrote pointedly: ‘to restore silence is the role of objects’. There is a poetic opportunity in the sweet specificity and ancient denominators, the slowness that comprises our discipline of art. As Globalism 1.0 plays out its economic endgame, this sentiment resonates as we again look to our ancient ritual of art for meaning.

In ceramics’ steadfastness it finds itself in a position to take advantage of a new longing for cohesion inside a world that’s looking not so much plural, as disjointed and confused. What ceramics and the discipline of art offers is an option, by no means conciliatory, that momentarily dislodges us, fiercely, oddly and with perspicuity from a pervasive style of thought. In this way ceramics is looking relevant not just to itself, but to a larger conversation about art and ideas, connected progressively to resistance.

|

Fig 3. Michael Jones McKean, The Teignmouth Electron, 1968 to present. The Teignmouth Electron is 40’ trimaran sailboat beached on the shore of Cayman Brac in the Caribbean for the nearly 25 years. In 1968, the boat was involved in a global race to circumnavigate the earth, solo, without stopping. In June of 1969 the boat was found ghosting in the Mid-Atlantic, some 283 days after the start of the race. The Teignmouth Electron’s pilot, Donald Crowhurst, was not on board. In 2007, I purchased the boat. The Electron remains on the shore of Cayman Brac. |

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated

Disciplined • Issue 12