Interpreting Ceramics | issue 12 | 2010

Articles & Reviews

|

Boundary-Work

Linda Sormin, Rhode Island School of Design

(transcribed from the presentation given at the College Arts Association conference February 2009, Los Angeles. Some images are omitted from the original presentation.)

| Contents | Home |

|

by Mary Drach McInnes The Convergence of Parallel Tangents by Timothy John Berg by Lawrence A. Bush by Rory MacDonald by Michael Jones McKean Interdisciplinary Mind, Deft Hand by Annabeth Rosen by Linda Sikora by Linda Sormin by Michael Tooby Modern British Potters and their Studios by Douglas Phillips A Guide to Collecting Studio Pottery by Juliet Armstrong by Leah McLaughlin by Alan Wallwork |

| NB. A Word document is available to download at the end of each article. |

My questions and motivations tumble out of the awkward, groping, messy interactions that I am experiencing in ceramics. For the past six years, I have made objects and installations that deal with issues of fragility and aggression, vulnerability and trauma. Using ceramics (including elements that are hand-built, thrown, slip-cast, fired, raw and found), I have collaborated with people from different communities to shape meaning and material presence in the context of their own, particular environments.

Salvage

This past August, I was invited to work in the gallery of Louisiana Artworks, New Orleans. My collaborators were local artists, students and teachers. They chose to bring things from home - monumental and intimate, broken and whole, ceramic figurines and industrial fragments - that had weathered Hurricane Katrina. They offered: industrial ceramic insulators, a plastic blow-up Scooby dog, glazed architectural façade bricks, string, broken pottery, a section of roof. We worked with raw clay and fired ceramics as our connective tissue. Through story-telling and hands-on making, we explored and enacted stories of vulnerability and aggression, trauma and survival.

|

Fig 1.‘Salvage‘, 2008. Ceramics and mixed media installation, Louisiana Artworks, New Orleans. |

Fig 2. ‘Salvage‘, 2008. Glazed ceramics and found wooden floorboards, New Orleans. |

Friend and collaborator Holis Hannan invited me to choose from objects stored under her house. Here I found an enormous hotel chandelier, an ornate metal park bench with four mermaids as legs, and a red elephant. Fig.3 and Fig.4 Moving upstairs, Holis showed me a high wall and near the top of the wall - several feet above eye level - were hundreds of deeply scored lines. Her roommate’s cat had survived the post-Katrina flood by frenetically clawing its way up this wall to the attic. Each day, the cat would leave the house to forage for food, then return to scale this seemingly impossible vertical plane. The claw marks were shockingly beautiful. Fig.5 They were marks of urgency, of survival. A sense of urgency is something that I observe more and more in the work of my students and colleagues, as well in as my own work. This pressing inquiry and vital process moves through what we make - and how and why we make.

|

Fig 3. ‘Linda in My House‘, 2008. Ceramic collaboration with Stephen Collier. Photograph by Stephen Collier. |

Fig 4. Holis Hannan and Caroline Smith were key collaborators in ‘Salvage’. |

|

Fig 5. Marks of survival made by a cat leaping to and from an attic during the weeks following Hurricane Katrina. Photographed by Linda Sormin. |

When Salvage closed, I dispersed all of the exhibition pieces to my collaborators‘ homes. Currently, sixteen people are reinventing the work. Every now and then they send me images of our fragments and forms that are resituated in their studios, houses, and backyards. For some these ceramic parts have become material to re-use in their own artwork.

As an artist and educator, I strongly support the development of depth and fluency in art practice, as well as engagement in interdisciplinary approaches. In the classroom and gallery, through inviting other people to build and un-build structures with me, I’ve been asking myself, ‘Why collaborate?’

To somehow test the work? To test ourselves?

To achieve feats one could never approach alone?

To encounter other makers?

To start new conversations?

And why move across disciplinary lines?

Clay in Context

In the ceramics department at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), I work with students from across the college - from ceramics to printmaking, film/animation/video, painting, furniture, teaching & learning, jewelry & metals, architecture, glass, landscape architecture and industrial design. In my ‘Clay in Context’ class during the spring semester in 2008, a cross-disciplinary group of students worked with clients/collaborators on and off campus to make ceramic and non-ceramic work. Projects ranged from the design and production of functional pottery for RISD’s professional catering and dining services, to outdoor guerilla art installations with students from a local high school, to video and performance work at a Columbian restaurant in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, to the invention of a mini-kiln that converts plastic milk bottles into spring planters for the local community.

For this last project, I supported the work of Industrial Design senior, Mike Hahn. Through assignments and self-directed research, this highly motivated young designer immersed himself in the haptic approaches and idiosyncratic culture of ceramics in the RISD studio. Mike was particularly interested in how ceramic artists generate ideas and forms, how we organize and communicate within groups, and how we engage the transformative processes of kiln firing.

Calling his project ‘Slugs’, Mike reached out to the local community with striking posters and combined hands-on clay research with his ID knowledge of blow molding. Fig.6 He designed a mini-kiln, constructed a series of prototypes and invited classmates and other local people to participate in designing, recycling and reinventing plastic milk bottles as planters for a neighborhood greening initiative. Mike engaged local passers-by by setting up a participatory booth on Benefit Street (Providence, RI) in the context of a RISD art fair. Fig.7 This work has been published online by the ID journal dvice (see video at http://dvice.com/archives/2008/04/reblowmolding_t.php).

|

Fig 6. Slugs Project. Industrial Design Senior, Mike Hahn, engages the local community with clay, plaster and a blow-molding device or "mini-kiln" that transforms used milk cartons into planters. |

Fig 7. Slugs Project. A neighborhood greening initiative by ID senior Mike Hahn in Linda Sormin's "Clay in Context" class, Spring 2008. |

Mike’s ambitious collaborations also include working with a computer programmer to design a responsive, kinetic web-based organism that connects RISD and Brown University professors, staff and students with each other for the purpose of exchanging ideas on research. Through group discussions, critiques, and hands-on, ‘wet clay’ brain-storming, our ‘Clay in Context’ class was able to support each individual’s work, expanding and deepening their projects - often through a non-verbal exchange of ideas.

Hostility/Un-building

The act of collaboration involves making space for hostility and aggression, vulnerability and fracture. In January 2007 I worked with students from St. Luke’s School in Regina, Saskatchewan who volunteered to create an installation with me at the Mackenzie Art Gallery. This group of sixteen year olds worked with me in the gallery for 3 of the 6 days of installation. Fellow volunteers included art patrons, gallery goers, mothers and grandmothers, children, professors and students, husbands and wives, clowns and breath and body workers. Issues of racial, social and economic privilege quickly surfaced through our interactions. In some ways, our personal connections helped to bridge gaps; in many other major ways they continue to confront me with questions ripe and raw in my practice.

How is it possible for me to navigate through the discomfort and ‘wrongness’ of working in a setting where obvious hierarchy determines nearly every interaction I might have with collaborators? As a teacher and an artist in the classroom and/or gallery, I am clearly in a position of power. What might it mean for me to make myself vulnerable and open throughout this process, or at the very least, how will I collaborate responsibly?

All of the participants, including St. Luke’s students, were invited to self-document their building and un-building processes with a video camera. They threw clay, made drawings and paintings, smashed ceramics and wrote their names and phrases on the gallery walls with slurry and vinyl lettering. One of the 9th graders, Leroy, boldly verbalized challenges to other makers as he was breaking objects. He had an excellent eye, quickly and astutely choosing to work with fragments and pieces made and donated by artists Rory MacDonald and Greg Payce.

Taking his turns as videographer and as subject, Leroy was keenly aware of the camera as his classmate, Jasmine, documented his actions and words (see Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 9, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue009/articles/02.htm ). Leroy’s physical and verbal call for response from Greg Payce has deepened my interest in relational aesthetics and dialogic practice. Playful and aggressive, he crushed pieces with a hammer and then his foot, saying, ‘Take that, Greg Payce, or whatever your name is… come to Regina, buddy!’ That message has since been passed on to Greg Payce, and perhaps he will accept the invitation sometime in the future.

After Leroy enacted his dramatic call for response, his classmate Charlene calmly took center stage on the same wooden platform (from which pieces of pottery were flying moments ago) and began to build quietly with shards and wet clay. She and Jasmine, along with many other collaborators, chose to work with material using rhythmic hand-building and intuitive drawing or painting approaches. Personal narratives were central to most everyone’s efforts, and marks of many people’s hands overlapped my own.

Wet Space/Digital Space

In Spring 2007, I team-taught a collaborative, community-engaged studio course, ‘Wet Space / Digital Space: Clay in Context’, with RISD Architecture professor, Hansy Better. My Ceramics students collaborated with behaviorally-challenged teens at Harmony Hill School in Chepachet, Rhode Island to make sculptural clay objects, and also with Architecture students to design three-dimensional screens incorporating these objects into the Harmony Hill counseling center. Fig.8 and Fig.9 It was our architectural goal to re-direct flow through this space, and many of our strategies were inspired by Neil Forrest’s piece, Hiving Mesh.

|

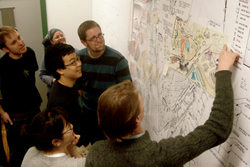

Fig 8. Wetspace / Digital Space. Ceramics students work with architecture students in a day-long charette to plan outdoor installations with students at Harmony Hill School, a residential school for behaviourally-challenged boys. Spring, 2007. |

Fig 9. Wetspace / Digital Space. Collaborations between the ceramicists and architects involve complex encounters and diverse approaches to research, cross-disciplinary communication and hands-on making. |

Professor Better and I created assignments that would integrate our core studios. Here are two examples:

Week 2

Using clay in its diverse states – from wet slip to soft to leather-hard, bisqued and glaze-fired – generate/model forms and ideas for the architectural screen. How might the objects be connected to each other and suspended in the wooden door frames? Discuss the nature of these joints, as well as ways to initiate the hands-on making process with Harmony Hill’s students. Ceramists will purchase the hardware necessary to demonstrate successful suspension strategy at next meeting.

Week 3

Using digital drawing tools and rapid prototyping, generate/model forms and ideas for the architectural screen. Resolve the hardware/connection issue: How will the objects be connected to each other and suspended in the wooden door frames? Discuss the nature of these joints, as well as ways to initiate the hands-on making process with Harmony Hill’s students.

This project demanded rigorous self-critique and intensive communication between collaborators, Harmony Hill staff, teachers and counselors. The act of collaboration can be confusing and anxiety-producing, particularly when people are from very different backgrounds, professionally and otherwise. Throughout the process, my students were asked to keep a journal. Here is an excerpt from the journal of one of my ceramics students:

Last time, Phillip was in a bad mood and resisted everything that I asked, I was worried and even tense. I kept thinking I need to be strong in front of Phillip!

He brought many drawings and most of them were floor plans of his dream house. He even let me read his poems which moved me a lot. Some of them made me very sad because I could see how he felt and his moroseness. It made me want to give him a big hug and console him, but of course I could not. Because they have a strict rule which I need to keep a certain distance with him, which made me more sad. Anyway, Phillip was enjoying showing me all of them.

In addition to being a springboard for class discussions and inviting active support from peers, professors and Harmony Hill staff/counselors, the student journals also created space for critique of our process, the course structure and the nature of our interactions. Here is a terse entry written by one of our ceramic seniors:

On the day of installation the project had changed again, and was drastically different form the original form or last idea … I felt that this solution was not as aesthetically pleasing as the previous solution and deterred from the design.

I felt the craftsmanship was shoddy and parts of the screen looked unintentional.

Overall what I learned was that for a successful collaboration communication is the most necessary element. Our group failed on this attempt and it became visually obvious when our screen was placed with the others. I had often made myself available to help, but my help was never requested. Our group had no leader to guide and direct our meetings or to initiate conversation.

Over the past few months, it has been a privilege for me to participate in a nomadic conversation with Mary Drach McInnes and diverse panelists. Meeting each other, many for the first time, through tele-conferences and then in person at our roaming panel (CAA in Los Angeles and NCECA in Phoenix), the participants are artist-educators from seven institutions across Canada and the United States. Together, we have been sharing our various perspectives – in some aspects resonantly similar, in other aspects starkly different – on collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches in our classrooms and in our own practices. It is our hope that this forum will open up new questions and possibilities for the education and practice of artists in ceramics.

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated

Boundary-Work • Issue 12