Interpreting Ceramics | issue 11 | 2009

Articles & Reviews

|

Ceramics in the West Midlands in the Late 18th Century: Production and Consumption through the Eyes of Katherine Plymley

Jo Dahn

| Contents | Home |

|

by Jo Dahn National Identity and the Problem of Style in the Post-War British Ceramic Industry by Graham McLaren Pushing the Boundaries of Ceramic Art Tradition in Nigeria: Notes on the ‘Suyascape’ Project by Ozioma Onuzulike Ceramics Without the Ceramics: Material Exploration in New Territories by Jane Webb Studio Pottery in Britain 1900-2000, book review by Graham McLaren Zelli Porcelain Award 2009, Competition review by Peter Holmes |

| NB. A Word document is available to download at the end of each article. |

Abstract

In this article I investigate how a particular group of consumers in the West Midlands area – the Plymley family and their circle – related to ceramics and ceramics production during the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century. My principle sources are the unpublished writings of Katherine Plymley and her brother Joseph Plymley’s A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire with Observations (McMillan, London 1803). I review and discuss the evidence supplied by these sources and argue that both Abolitionism and Quakerism influenced the Plymleys in their consumption of ceramics, especially Coalport China.

Key words: Plymley; Coalbrookdale; Coalport; Wedgwood; Abolition; Quakerism; design history; consumption; gender; emulation; tea table; objectscape

In his examination of the relationships between manufacturing, consumption and design, John Styles remarks on the lack of evidence. He considers that a thorough history of design in eighteenth century Britain ‘has yet to be written’. It will require ‘investigation of all aspects of what might loosely be termed their [the ‘manufacturing trades’] and their customers’ visual culture’.1 This essay offers a contribution towards that investigation. It concerns the production and consumption of ceramics, as perceived amongst a particular group of people at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth. My principle evidence is the archive pertaining to the diarist Katherine Plymley (1758-1829), which includes travel journals, study notes and memoirs as well as 138 diaries.

|

Fig 1. ? Katherine Plymley; notebook closed. (Shropshire Research and Records Office). Katherine Plymley used unformatted notebooks and her text sometimes runs on from one to the next. There is no regular pattern to the amount of time covered by each diary. One notebook might deal with the events of just a few weeks, while another might cover several months. |

Fig 2. Katherine Plymley; notebook open. (Shropshire Research and Records Office). |

Katherine Plymley lived at Longnor, near Shrewsbury in the West Midlands, an area that saw some of the earliest manifestations of the industrial revolution and was home to what has been called ‘the Shropshire enlightenment’.2 She lived with her sister Ann, an invalid who was rarely well enough to venture from Longnor; they had one brother, Joseph, who became Archdeacon for Shropshire in 1792.3 After his wife died (c1786), Katherine and Ann – neither of whom married – took responsibility for educating his children; ‘… it has been a motive to endeavour to increase our own knowledge,’ Katherine Plymley wrote, ‘that we may be more capable of informing them’.4 Both sisters studied Natural Sciences; Katherine specialised in entomology, Ann in botany. They were conversant with the latest scientific developments and their scholarship was respected further afield as well as in their local community.5

In what follows I also draw on Joseph Plymley’s A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire with Observations.6 Here ‘Agriculture’ translates very broadly; ‘Natural Resources’ (including human resources) better conveys its content today. The book amounts to a stock-taking report on the state of the county, balancing ‘Obstacles to Improvement’ against ‘Means of Improvement’.7 There is a strong moral subtext. ‘Obstacles’ are very often construed as poor social practices of the past; ‘Improvements’ as the projected result of individual attention to duty and moderation in lifestyle, as well as the judicious organisation of natural resources and the application of scientific method. The General View was commissioned in 1795 by the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement. From its inception two years earlier under the aegis of Sir John Sinclair, the Board had instituted a system of information gathering on a national scale that involved correspondence with eminent figures across the country. Several members of the Lunar Society were involved; Matthew Boulton, for example, ‘... wrote ... of his plans for irrigation and land improvement’.8 Erasmus Darwin was another of Sinclair’s correspondents.

Joseph Plymley discussed the progress of his Shropshire report with his sisters. It was several years in the making and statistics were provided by a succession of experts. When people like this visited him, as Katherine Plymley remarked, ‘... my Brother has the goodness to ask me … knowing I enjoy listening to such society’.9 Some of her diaries contain verbatim copies of letters between her brother and the Board of Agriculture, others include notions of best practice from the report woven into descriptions of landscape and architecture.

British society changed considerably during Katherine Plymley’s lifetime, with the emergence and consolidation of a self confident middle class. The development of a capitalist economy based on the manufacturing industries – in which ceramics production played a leading role – has been centralised in studies of middle class socio-cultural structures, particularly consumerism.10 In associated matters of taste, Veblen’s theory of social emulation has been readily cited by design historians as a primary motivation.11 But while aspects of middle class taste could be, and often were, constructed in direct response to notions of social change, the new middle class did not necessarily emulate the condition of the aristocracy. In some important quarters middle class values and their expression resided in a critique of upper class behaviour and this was true of the Plymleys.

Abolitionism, Quakerism, Consumerism

Katherine Plymley’s accentuated sense of social conscience makes hers a fascinating example of principled, ‘rational’ taste. It would be a mistake though, to think of her as a strait-laced reformer given to polemic. She was a thoughtful woman who respected the opinions of others. A practising Anglican herself, she was very interested in the religious debates of her day and her writing attests to her sympathy for dissenting Christian views. ‘... I have always respected the right of private opinion upon the most important of subjects,’ she stated in 1812, ‘this is a subject between God & our conscience ...’12 The Plymleys were abolitionists and the Quakers excited Katherine’s special attention for their role in the anti-slavery movement. She was struck by ‘the plainness of their dress and appearance, & the simplicity and yet independence of their manners’.13 Discussion of the influence of dissenting Christianity in visual culture has been dominated by the Quaker code of ‘plainness’; Marcia Pointon refers to the ‘invisibility’ of Quaker artefacts, and cites Quaker directives on the nature of designed objects.14 Representations, even of religious subjects, were disallowed. Furniture was to be functional: ‘… painted hangings, shining tables and looking glasses should … be eschewed’.15 Even household ceramics could be dangerous, if they formed part of an ostentatious display:

refrain from having fine tea-tables set with fine china, being it is more for sight than service ... It’s advised that Friends should not have so much china or earthenware on their mantelpieces or on their chests of drawers, but rather set them in closets until they have occasion to use them.16

The stereotypical Quaker of popular imagination was a dour individual, dressed in unremitting black with a hat that he refused to doff under any circumstances. However, the abolition movement prompted a reappraisal of Quakerism and amongst Katherine Plymley’s circle Quakers were thought to have

high cultivated minds, general knowledge, and even a strong taste, as well as a considerable acquaintance with the polite arts; but with a still stronger restraint, circumscribing them within the limits of chaste simplicity.17

Like her brother, Katherine Plymley was driven by a highly developed notion of progress; she was attracted to those who achieved success in their chosen fields through effort. Self-education, will power and a desire to act for the betterment of society were qualities she looked for. Here is her assessment of Josiah Wedgwood:

early in life Mr Wedgewood [sic] was a working potter from which situation he has raised himself by his own abilities & industry to his present opulence & he has now long enjoy’d the fortune he so honourably gain’d.18

In 1791 Katherine spent two days at Etruria, Wedgwood’s mansion in Staffordshire, ‘in the society of an enlighten’d & good family’. She thought the mansion

a very handsome one, furnished with all the appendages necessary not only for convenience but elegance, hot-house, ice-house & the very large potteries by which Mr Wedgewood has realized the large fortune & the property are at a small distance from the house & present a scene of busy life rarely found so near an elegant seat.19

Inside she was struck by the ‘very elegant’ drawing room with a ‘beautiful chimney piece of Mr Wedgewood’s own composition the ornaments very chaste white on a blue or rather french grey ground’.20

|

Fig 3. Wedgwood ‘Ceres’ jasperware and marble fireplace c1786. (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool Museums Service). http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ |

Katherine Plymley’s use of the term ‘chaste’ to describe Wedgwood’s neo-classical designs recalls the ‘chaste simplicity’ associated with enlightened Quakerism and it is worth noting that despite his famous exploitation of the emulative urge in marketing his wares, Wedgwood’s products also appealed to people whose taste was formed along quite different lines. He trialled new styles on Quaker women, was keen to sell to Quaker households and was prepared to modify his designs accordingly.21 In 1769 he wrote to his partner Bentley:

It will be of great importance to have the service for my friend Barclay as neat and fine as possible. The Quakers have for some time past been trying my ware, & verily they find it to answer their wishes in every respect, they have now order’d this full set. As my future recommendation to the brethren must depend on their usage in this sample, a word to the wise is enough.22

There were many connections between the Plymleys and the Wedgwoods. They had friends, like Dr Erasmus Darwin, in common and both families energetically espoused the abolitionist cause. In fact it was abolitionism that caused Katherine to begin keeping diaries in 1791. In October of that year Thomas Clarkson, who collected evidence to support Wilberforce’s parliamentary campaign, made the first of several extended visits to Longnor. Katherine Plymley realised that she was living in ‘interesting times’ and decided to record them.

Deeply interested in the abolition of the slave trade & impressed with the most exalted idea of the character of Mr Clarkson in consequence of the part he took in it, his first visit to Longnor was a sufficient incitement to me ... to assist my memory by written memorandums of some particulars that appeared interesting to me. This has insensibly brought on a habit of preserving ... the recollection of incidents of various kinds that I did not at first intend, for the part taken by my Brother in the subject of the slave trade & the incidents connected with it was what I first proposed ...23

Abolitionism politicised its adherents. They found themselves considering, not just the slave trade, but the social and cultural structures that supported and were supported by it; they became aware of the origins of consumer goods and promoted public awareness of consumer behaviour. The movement coloured Katherine Plymley’s view of whomever she encountered; she tended to mistrust the aristocracy, because she saw them as supporters of the slave trade.24

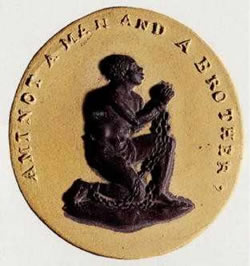

Via Wedgwood, ceramics played a prominent part in the abolition movement. In 1790 he issued an anti-slavery cameo plaque entitled Am I Not a Man and a Brother.

|

Fig 4. Wedgwood jasperware plaque ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’1790. |

Large numbers of the plaques were distributed for sale in support of the cause. Clarkson received five hundred and is likely to have dispersed them all over England; Katherine Plymley, whether or not she owned one, must have known of them. The plaque was also produced in smaller versions, mounted as buttons, broaches etc. Such objects politicised personal display; in some sense they imbued vanity with moral content. Wedgwood sat on the committee of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery, made cash donations to the cause, and wrote letters to a range of individuals. Joseph Plymley was amongst his correspondents, and Anna Seward was one of those converted through his efforts.25 In 1792 he paid for Am I Not a Man and a Brother to be used as the frontispiece for a pamphlet by Clarkson.

The Plymleys were active in the campaign to refrain from using sugar that had been produced by slave labour. Katherine Plymley noted Clarkson’s commendation of ‘... that little pamphlet, intitled [sic] an address to the people of Great Britain on the consumption of West-India produce’.26 This pamphlet, and a similar publication of the following year, played on the sensibilities of the feminine consumer. Both involved repulsive descriptions of sugar production ‘by an eye witness to the facts related’.27

Shropshire retailers, notably Eddowes of Shrewsbury and Wright of Haverhill, supported the campaign. Eddowes distributed pamphlets and Wright placed a notice in the local newspaper ‘stating his reasons for declining selling Sugar – he mentions the iniquities of the slave trade & says he cannot with a safe conscience trade in that article till he can procure it through a purer channel’.28 The abolitionists could be regarded as the equivalent of today’s ‘ethical’ consumers. Rather than endure complete abstention, influential families at the centre of the movement were turning to other sources:

Mr Wedgewood’s family would not have any West India Sugar, from a principle of not giving encouragement to the Slave Trade … when I was at Etruria in May last they none of them eat sugar as the quantity they had sent for from the East India’s was not then arriv’d. 29

The Plymleys also imported sugar from the East. Joseph Plymley ‘order’d various sorts as samples, the Loaf Sugars are very good & some of the browns the cleanest & finest I ever saw, the maple sugar has a peculiar taste not quite unlike very sweet damson’.30 When Clarkson visited Longnor in 1791 he brought news of the Sierra Leone Company which was set up to supply other goods that abolitionism proscribed. He spoke ‘of the wonderful fertility of the soil, & the great number of articles it would produce for commerce’. He had samples, including pepper, ‘... which I tasted & found very warm & agreeable & he had two or three beans, which he told us had much the taste of coffee. ... Mr H. put the two or three that were here in the fire shovel & held them over the fire, they smelt very well’.31 It has long been established that people express their sense of identity in the process of consumption. Clearly the very act of enjoying a flavour could be experienced politically. Amongst Katherine Plymley’s acquaintance the handling of the china service would have had political resonance. The woman who handed round tea or coffee without offering sugar, in that action affirmed a political stance. A woman like Katherine Plymley may have been reminded of it every time she took out the cups and saucers.

Coalbrookdale, Coalport China

With its numerous industrial developments, especially – for the purposes of this essay – ceramics production at Coalport, the Coalbrookdale valley afforded Katherine Plymley many examples of the right way to instigate social change.32 The area was dominated by influential Quaker families, principally the Darbys and the Reynolds, who had put into practice some of their ideas about the organisation of society.33 They considered it their duty to trade fairly and there is plenty of evidence that points to their exertions on behalf of the workforce. They provided decent accommodation and built schools; factories were shut down on Sundays so as to maintain the day ‘free for worship or recreation’, despite the technological problems this caused.34 Joseph Plymley praised Quaker ironmaster Richard Reynolds’ efforts and noted that between 1782 and 1793 the population of Madeley Parish, which encompassed Coalport and Iron Bridge, increased from 2690 to 3677. (Reynolds had bought Madeley Manor in 1781.) Plymley believed that people could be ‘improved’ if their material circumstances were enhanced and his examination of wage rates showed that industrial workers at Coalbrookdale generally earned more than their agricultural counterparts.35 The section on minerals in his report was contributed by William Reynolds, son of Richard Reynolds. It includes references to fossils as well as six pages entitled ‘lists of strata in five different collieries,’ significant information for the ceramics manufacturer.36

A vivid diary entry describes Katherine Plymley’s 1794 outing to Coalbrookdale in the company of friends and family:

June 4th ... The weather was very favourable ... got to the Ironbridge Inn late in the evening, walked through part of the walks planted by Mr Reynolds, & which he permits the public to enjoy, till we reach’d the Rotunda placed on Lincoln Hill, the pillars of it are cast Iron – from whence we had a fine view of the Dale by night. – the numerous fires have a fine effect, not only there in the Dale but several other works towards Broseley, Madeley &c. The next morning after a delightful walk through other plantations of Mr Reynolds we reach’d the Dale & look’d at the works [...] it is wonderful to see the vivid green of the plantations so near the smoke of the works, in the close walks it may be supposed that we are in a rural & retired spot, at convenient distances are placed seats which command views of a romantic country & discover how near we are to busy life; there is something in this contrast very pleasing ...37

|

Coalbrookdale stimulated the imaginations of many people. At the end of the eighteenth century, the Iron Bridge was regarded as a modern wonder of the world. It was featured on a range of objects, ceramic and otherwise. Some were typical souvenirs, such as an enamelled snuff-box, made in Birmingham c1790, and entitled ‘A Present from the Ironbridge’. Ceramics included a Caughley ‘mask-head’ jug with a transfer print design and a hand-painted, gilded jug from the early days of the Coalport factory.

|

Fig 6. Caughley mask head jug showing the Ironbridge and probably made to commemorate the completion of the bridge in 1779.

(Courtesy of Coalport China Museum.

For more images of ceramics in their collection, go to: http://www.ironbridge.org.uk/collections/our_collections/ |

Fig 7. Coalport hand-painted jug showing the Ironbridge; after 1779. |

The difference in quality (and price) between these two jugs suggests that demand came from a range of socio-economic backgrounds. As components of domestic displays both surely signalled pride in or at least admiration for, the achievements of British industry. In the ceramics museum at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence there is a salver showing a popular print depicting the Iron Bridge. Originally part of Napoleon’s collection, its presence there gives some indication of the extent of the bridge’s celebrity.

The Plymley party made a point of arriving at Ironbridge late in order to appreciate the dramatic night view of the industrial scene from a specially constructed vantage point: the ‘Rotunda … on Lincoln Hill’.38 The ‘... several other works towards Broseley, Madeley &c’ that they saw would have included the Caughley China Works and the Jackfield porcelain manufactory (the precursor of the Coalport China Manufactory) owned by Edward Blakeway and John Rose; the latter was the brother in law of Quaker William Reynolds.

Katherine Plymley admired the juxtaposition of industry and landscape at Coalbrookdale: ‘the vivid green of the plantations so near the smoke of the works [...] there is something in this contrast very pleasing’. Following his purchase of the Manor of Madeley, Richard Reynolds had planted shrubbery and made a series of walks in the countryside surrounding the industrial sites. Aristocrats in the West Midlands typically incorporated classical style gazebos and suchlike architecture in their estate gardens, and carefully designed walks linked the separate features.39 But the walks at Madeley were known as ‘The Workmen’s Walks’. They were an example of the Quaker industrialists’ efforts to improve the lifestyles of their workers. Reynolds’ granddaughter gave an account of them in 1852:

he had great enjoyment in planting and improving these estates, and laying out walks through the woods. Those upon Lincoln Hill ... were made expressly for the workmen, and seats were put up at different points, where they commanded beautiful views; they ... were a source of much innocent enjoyment, especially on a Sunday, when the men, accompanied by their wives and children, were induced to spend the afternoon or evening there, instead of at the public house.40

In April 1814 Katherine Plymley and her niece Mildred accompanied her nephew Panton Corbett and his bride on another trip to Coalbrookdale; this time in order to visit the Coalport China Manufactory. Her diary entry records the purchase of a dessert service. It would probably have been more customary to make such a purchase before the wedding, but this may have been an advantageous moment to buy Coalport. The management history of the company is complicated. January 1814 saw the end-game to almost twenty years of manoeuvres that resulted in the establishment of the Coalport China Manufactory, led by John Rose, brother-in-law to Quaker William Reynolds. The previous owners had been declared bankrupt; they had intended to auction their stock in London, but bad weather, ‘... prevents the removal with safety from the manufacturer’s warehouse and the manufactory, of the most valuable articles of this splendid stock’.41

Geoffrey Godden has written the definitive history of Coalport. He was unable to trace the bankrupt stock, and suggests that ‘the partners may well have found other means of disposing of it – perhaps at reduced prices to their former customers, or in sales nearer to Coalport’.42 The stock may have been sold off cheaply by the new management. Timed as it was, the Plymleys’ visit may have included an economising element. Or they may simply have anticipated viewing a more extensive range than had previously been available, in a factory that was now established as the leading china producer in the area.43

Katherine Plymley’s view of Coalport was positive:

The display of China both useful & ornamental was beautiful, they have arrived at great excellence, the price of the richest Dessert set was thirty guineas, another very handsome twenty five, Mrs Corbett bought an elegant Dessert set of white & gold for nine – We saw the whole of the manufactory which is very curious.44

However, Randall’s History of Madeley contains a very different account of the same china works, albeit sixty six years later:

The works themselves are ill designed and badly constructed, the greater portion of them having been put up at the latter end of the past and beginning of the present centuries, whilst other portions were added from time to time, with no regard to ventilation or other requirements of health ... In entering some of these unhealthy ateliers and passages strangers have to look well to their craniums. Some work-rooms have very stifling atmospheres, charged with clay or flint; the biscuit room notably so.45

Even allowing for the deleterious effects of time on the condition of the buildings, this is a far cry from Katherine Plymley’s attitude. It would not have been in character for her to gloss over unpleasant or unhealthy working conditions, or ugly premises, so presumably she saw nothing objectionable about the works. Randall seems to have taken for granted that industrial buildings of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries would be ‘ill designed’ because of their period, whereas I suspect Katherine Plymley would have thought the opposite for precisely the same reason. She must have ignored a number of factors in her response to Coalport and Coalbrookdale. The smell, for instance, and the lead works which was ‘vastly poisonous, and destructive to everything near it’.46 Such factors were diminished because for her industry evoked notions of individual opportunity and national prosperity. She thought ceramics production at Coalport had ‘arrived at great excellence’ (my emphasis) implying a process of improvement, a quest for excellence.

Coalport is discussed under the general headings of both ‘manufactures’ and ‘commerce’ in Joseph Plymley’s 1803 report to the Board of Agriculture. It was greatly advantaged by the development of the local canal system. Thomas Telford supplied information on this subject:

the works at Coal-port . have succeeded to a very considerable degree, and are striking proof of the good effects of an improved inland navigation ... houses to the number of thirty have been built there, and more are still wanted to accommodate the people employed at a large china manufactory ... in which perhaps the last, and including its dependencies, the most china is manufactured of any work of that sort in Great Britain.47

Plymley’s report was, as previously noted, an assessment of the natural resources of Shropshire. He set out to investigate both ‘the riches to be obtained from the surface of the national territory’ and ‘the mineral or subterraneous treasures of which the country is possessed’. These included clays suitable for ceramics manufacture. ‘In the lordship of Cardington, in this county,’ he enthused, ‘a quartz and clay may be gotten for compounding this ware, the former superior, as I am well informed, to that imported out of Carnarvonshire [sic] to the Staffordshire potteries’.48 Plymley’s ultimate goal was to identify ‘the means of promoting the improvement of the people’ and he saw the manufacture of china at Coalport as instrumental in achieving that end.49 By the application of modern scientific knowledge, such as the information contained in his report, ceramics production exploited naturally occurring materials in a suitably progressive way. There was even a sense in which ceramics could be conceived as a fruit of the earth. Moreover, the Quaker influence at Coalport seemed to ensure a moral responsibility towards the workforce. Worker housing was provided by Quaker William Reynolds and leased to tenants under favourable terms. When one adds abolitionist sympathies to the mix it is not surprising that the Plymleys would have bought Coalport china.

From the Factory to the Parlour

After an object or a set of objects has been acquired, it is incorporated within the household and is subject to a process of appropriation whereby individuals invest it with personal resonance, so that it accrues meaning(s) in addition to (sometimes in denial of) its significance at the point of purchase. Ceramics generally occupy a central position in domestic display and in Shropshire interiors the Coalport china service would have been a potent sign of social change. Joseph Plymley compared the ceramics produced in the West Midlands to the imported oriental porcelain favoured by the aristocracy; he applauded the similarity between them.

At Caughley … is a china manufacture of great excellence. The blue and white, and the blue white and gold china there, is in many instances, more like that from the East than any other I have seen ... At Coal-port coloured china of all sorts, and of exquisite taste and beauty, is made.50

|

Fig 8. Caughley teapot, late C18, (Coalport China Museum). |

The ‘rational’ society that the Plymleys favoured constituted a departure from established upper class manners. Joseph Plymley recommended an informal, mixed gender assembly at home. He despaired of those who, seduced by fashionable society, entertained competitively to ruinous effect. Instead they should ‘...cherish real hospitality, in a degree suited to their fortunes, but let them discountenance all exhibitions of show, all competitions in luxury, all frivolous entertainments; let them guard against excess in any species of entertainments’.51 There are echoes of Quakerism in his recommendations; progress required restraint. ‘The increase of domestic visits,’ he wrote, ‘bespeaks the improved taste of the age. In private visits there would certainly be more comfort and more enjoyment ... more decency of behaviour, and more room for rational and improving conversation’.52 Many comments in Katherine’s diaries show that she was of the same opinion. The ‘home grown’ china service fitted and facilitated the kind of social intercourse that they envisaged. Families of moderate means need not aspire to a show of inherited silver plate, or to serve meals off expensive imported porcelain. By displaying and using British table-wares they could support and celebrate national enterprise; feel themselves part of a progressive society. As Sarah Richards has remarked,

In the middle-class home such products brought comfort acquired through a measure of refinement, taking into account one’s station in life and not always wanting to rise above it.53

There is one account in Katherine Plymley’s diaries that points to the significance of owning a set of ‘best’ china that was reserved for special occasions and presented in ritual – perhaps emulative – fashion, certainly with pride. Following her brother’s success in a long drawn-out court case, his tenants organised a celebration with dancing and refreshments. The Plymleys were expected to stay for tea, but there was a misunderstanding ...

Tea was getting ready in the house, & a very nice set of tea china was set out in the smaller room, the larger was full of men; there was likewise a nice Simnel put ready for us; we hesitated whether we ought to stay [for] tea, & at last determined to return home; knowing there were such numbers to whom the tea would be an object, we thought it may at least be as well not to take up the room & attention to our accommodation that our stay would occasion ...54

The Plymleys thought the meal would be more of a treat to their tenants than to themselves. What they failed to recognise was that as the local gentry, their presence at the tea table was part of the treat:

We heard afterwards that we had made a mistake in coming home to tea; Mrs Shukar’s best china was laid out on purpose, & hot cakes &c was all ready; Mrs Watson quite stampt her foot when she heard we were gone; I was sorry & thought how I could remedy it.55

There were plenty of others willing to consume the tea and cake, but Mrs Shukar and Mrs Watson had been counting on Katherine Plymley and her family. They had made a special effort and it had gone unrecognised; their purpose in laying out their best china was thwarted. Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace has discussed the performance of the tea ceremony; as she explains, every action could be imbued with meaning:

Gestures, often organized to show off an expensive tea equipage to its full advantage, were to be predictable and organized. The correct placement of a spoon carried significance, while other facets of the tea ceremony – the placement of the guests themselves, the handing round of cups, and so forth – also conveyed meaning.56

With its different parts requiring specialised handling, the tea service functioned not just as containers for food and drink, but as a set of objects that demanded a certain form of behaviour. Presiding over the tea table was an important feminine role. No wonder ‘Mrs Watson quite stampt her foot’ in frustration. She had been denied the opportunity to perform before the audience she most wanted to impress.

Katherine Plymley sometimes remarked on the skill with which her nieces served tea and coffee. In 1811 she recorded a conversation that suggests this was a role to which they actively aspired. Harriet, one of her nieces, had made a rapid recovery from illness:

Mrs Corbett observed how soon these little creatures recovered, 'they, said she, have nothing upon their minds to trouble them & keep them back like older people.” – “No, said little Harriet, “I have nothing but what is to cheer me, the thought of getting well enough to pour out Coffee for the Judges.” And she did get well enough to do so … she looked pale & delicate, but very nice, & was very attentive at her table with the Coffee, & of course much noticed by the gentlemen; Matilda was at the tea table ...57

The coffee and tea tables framed Harriet and Matilda, presenting them to the assembled company; the correct handling of the tea and coffee services provided them with meaningful activity. Harriet’s ‘pale and delicate’ appearance suggests a correlation between her (feminine) person and the china objects she manipulated, to which the same epithets might well have been applied.

|

Fig 9. Coalport teapot, late C18, (Coalport China Museum). Despite its delicate design, this pot requires skilful handling. It is surprisingly heavy and difficult to control, with a rough, unturned base. |

In an earlier essay I discussed ceramics in the ‘objectscape’ of the aristocrat Mary Delany (1700-1788).58 There are no equivalents to Mrs Delany’s accounts of elegant dining in Katherine Plymley’s writing, and no exuberant descriptions of decorative feminine objectscapes amongst her immediate circle. However, the Plymley sisters probably inherited ceramics from their mother’s ‘cottage,’ a small gothic style building in the grounds of the family home, where she entertained her female friends and where she may well have constructed a species of objectscape.

my Mother happened to express a wish for a house in a wood, this suggested to my Father the idea of building a cottage in his infant plantations & in 1762 he built one; it consisted of a kitchen & a room over it, in the true cottage stile, & a beautiful little gothic parlour ...59

Women had sites like this, separate from the main household, where they accumulated collections and created personal objectscapes. Moira Vincentelli has observed that ‘china collecting can clearly be recognised as a ‘female space’ where women exercised some power and independence’.60 She also points out that men sometimes supplied an appropriate venue. It seems likely that friends of Katherine Plymley’s mother made contributions to the cottage; in a diary entry of 1810 she reminisces about one such friend, Miss Edwards, whose family residence, nearby Frodesley Hall, fascinated her as a child:

When I was a child I used to accompany my Mother to drink tea there once or twice in the Summer, & looked forward to these visits with high pleasure … the house itself, like a little Castle, its thick stone walls, its castle like windows, its old Porch, its Balcony, its small bason in front with a Duck spouting water, all delighted me; the drawing room was modern, & everything was Chinese within it, I cannot imagine any enjoyment that can arise from place greater than I had in examining all these Chinese ornaments with which it was almost crowded.61

The passage evokes an elite, fashionable and expensive interior; the ‘Chinese ornaments’ were probably imported porcelain. The Edwards family suffered a reversal of fortune and Miss Edwards slid down the social scale, until

One trait of herself remained, she had been accustomed to bring my mother some token of her remembrance, a Fan, or some such toy – She now produced, (when we were in the pretty Cottage built by my Father in this garden, since taken down) an imitation of a bit of old candle with the snuff as if blown out, very well done, this she placed in one of the old fashioned brass candlesticks over the mantle piece saying, “I did not forget the Cottage,” it was prettily done ...62

The ‘imitation of a bit of old candle with the snuff as if blown out’ may well have been a piece of novelty ceramic ware, but one cannot be sure. Descriptions of the appearance of the ceramics Katherine Plymley encountered are conspicuous by their absence. There are exceptions, however. On a visit to London in 1796 she visited ‘Christies Auction room in Pall Mall’, where she viewed an array of French porcelain:

I was gratified by seeing more fine china than I ever had an opportunity to see before, not only useful but ornamental such as flower vases, &c two patterns particularly pleased me, wild Poppies, & a garland of china roses & laylock both beautifully painted – There was besides a number of elegant articles particularly lustres & candle branches of various sorts.63

It was the morning of the 14th April, and the sales catalogue has survived. Several lots correspond broadly to the patterns she mentioned. Perhaps the most likely candidate for her ‘garland of china roses & laylock’ is ‘A desert service painted in blue roses and purple sprigs, 52 pieces including 36 plates.’ Another possibility might be ‘A centre for a lady’s work table, painted in garlands of roses, of the Seve [sic] manufactory.’ Her ‘wild Poppies’ may have adorned ‘A very capital square flower case richly painted with groups of poppies.’ There are several other items listed with ‘boquets [sic] of poppies’, however. 64

|

Fig 10. Sevres bulb pot vase 1759-60; (The Wallace Collection). This vase may be similar to those that Katherine Plymley enjoyed at Christies. To view other Sevres ceramics in the Wallace collection, go to: http://www.wallacecollection.org/the collection/collections/ceramics |

The inclusion of prices in Katherine Plymley’s diary entry on Coalport makes it possible to identify shapes and patterns that may correspond to her account. She divided the dessert services on show into three categories: ‘the richest’, ‘very handsome’ and ‘elegant’... the price of the richest Dessert set was thirty guineas, another very handsome twenty five, Mrs Corbett bought an elegant Dessert set of white & gold for nine.

‘The richest’ is likely to have been non-standard shapes heavily decorated with much handwork, of which small numbers were made. They featured oriental-style patterns inspired by imported porcelain, in deep colours with a profusion of gilding.

|

Fig 11. The ‘richest’ Coalport china? |

Fig 12. The richest Coalport china? |

‘Very handsome’ was quite similar in depth of surface to ‘the richest’, but made in standardised shapes. The Coalport ‘London shape’ would fit into this category.

|

Fig 13. The richest Coalport china? Coalport covered serving dish c1805-1810. (Coalport China Museum). |

Fig 14. ‘Very handsome’ Coalport china? Coalport plate c1805-1820. (Coalport China Museum). |

|

Fig 15. Elegant Coalport china? Tea ware in the ‘London’ shape c1803-1807. (Coalport China Museum). |

Fig 16. Elegant Coalport china? Coalport teapot; John Rose tea ware class C, c1803-1807. (Coalport China Museum). |

A great part of the Coalport produce would have fallen into the ‘elegant’ category, much of it in white and gold.65As the illustrations show, the appearance of the ‘elegant’ Coalport china has little in common with imported oriental ceramics. It is more closely aligned with Wedgwood’s neo-classical styles, described by Katherine Plymley as ‘chaste’, and looks relatively restrained beside ‘the richest’ and ‘very handsome’ varieties. The simpler surface enhances one’s awareness of the form.

|

Fig 17. 'Elegant' Coalport china? Decorative serving dish c 1805-1810. |

Fig 18. 'Elegant' Coalport china? Sucrier in gilt 'vermicelli' c 1805-1810. |

Marcia Pointon has asserted that: ‘A human subject clothed and shod is an art-work as is a table laid with crockery and food,’66 and it seems likely that there was an element of self-portraiture in Mrs Panton Corbett’s choice. She opted for the ‘elegant Dessert set’ in white and gold, actively encouraging a perceived correlation between herself and her china. I think Mrs Panton Corbett selected the dessert service that complemented her style of dress:

… she was dressed in white satten trimmed with three rows of broad lace full round the bottom of the dress, the sleeves & neck likewise trimmed with lace, a white satten sash, a handsome pearl broach, a lace scarf, white shoes & gloves, her hair dressed simply & without any ornament, & she wore no ornament round her neck except a gold chain to which her short-sighted glass was attached ...’67

|

Fig 19. Dress 1813-1817; cotton muslin and silk satin. (Museum of Fashion, Bath). This image can be found here: http://www.fashionmuseum.co.uk |

Concluding Remarks

From Abolitionism to Quakerism to Coalbrookdale and Coalport and thence to the tea table and the fashion plate; diaries do not necessarily mirror or even parallel the contents of the history book. Their narratives can be fluid, wandering, nostalgic and frustrating; sometimes dwelling on mundane minutiae, yet perfunctory where one longs for detail. If ownership of objects is specified, too often the account is only of their acquisition and disposal; even then descriptions are rare. How can one be certain as to how those objects signified; why one was chosen over another; what it meant to interact with them? Katherine Plymley’s diaries are littered with examples of visual culture: she visited houses that were being ‘improved’, commented on art collections and exhibitions, gave details of interior decorations and related incidents concerning the disposition of artefacts. It would all mean very little without understanding of the contributory factors that informed her interest and directed her ‘gaze’. The breadth of her archive is significant, in that diary content can be read against opinions expressed in other modes of writing. Her study notebooks, for example, contain searching personal reflections alongside extracts from her reading. Frequently she reveals a philosophical stance whereby day-to-day events are considered in relation to a wider intellectual discourse. Although specific references to ceramics are relatively few in her diaries, when read in tandem with the mindset evinced in the study notebooks, or indeed in her travel journals and memoirs, as well as diary accounts of other subjects, the evidence comes to life.

In private – predictably – ceramics were central to the performance of domestic rituals, especially significant for women. Mrs Shukar and Mrs Watson were obviously proud of their ‘very nice set of tea china’; their efforts to serve tea to the Plymleys and their disappointment when they were thwarted suggest that emulation may also have been a motivating factor. In abolitionist circles, the meanings constructed via the tea ceremony were reconfigured and when women like Katherine Plymley served unsweetened beverages they invested their handling of the cups and saucers with political content.

Amongst the Plymleys’ abolitionist milieu, direct Quaker involvement in the production of Coalport china is likely to have enhanced its desirability. Importantly, Coalport was also regarded as an embodiment of the latest scientific approach, exemplified in Joseph Plymley’s report on Shropshire. Its ‘great excellence’ was the result of a process of enquiry to discover and transform natural resources into beautiful objects. Consumers like Katherine Plymley idealised the manufacture of ceramics in the West Midlands as a function of a forward looking society, informed by a respect for Quaker mores. A middle class utopia where enterprise was rewarded with prosperity: a benevolent capitalist meritocracy.

Notes

- John Styles, ‘Manufacturing, Consumption and Design in Eighteenth-Century England’ in Brewer, John and Porter, Roy (editors) Consumption and the World of Goods, London, Routledge, 1994, p.548. back to text

- Hugh Torrens, ‘Mineral Exploitation and “Revolution” in the Shropshire Region 1650-1850’ unpublished conference paper, Science for Life, Keele University 29/8/93 – 3/9/93. One might think of the rural West Midlands as the intellectual hinterland of the urban Lunar Society. See: http://www.lunarsociety.org.uk/3 back to text

- Joseph Plymley changed his surname to Corbett in 1806 after he succeeded to the Corbett estate. back to text

- SRRO 1066/141 Memoirs of my Father 3rd. back to text

- The Plymleys belonged to an influential group of families in the Shrewsbury area that included the Darwins and the Gilpins. Amongst their other contacts were naturalists Dr William Withering (1741-1799), Robert Townson (1762-1827) and Thomas Pennant (1726-1798). Katherine Plymley was an accomplished painter of entomological subjects and over 500 of her paintings have survived. She derived great pleasure from the study of natural history; she and her sister had built up a collection that was well known amongst their circle. back to text

- Joseph Plymley MA, A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire with Observations McMillan, London 1803. back to text

- Plymley 1803, p.xiii. back to text

- Robert E. Schofield, The Lunar Society of Birmingham, a Social History of Provincial Science and Industry in Eighteenth Century England, Oxford, 1963, p.397. back to text

- SRRO 1066/78 (19/6/1809 – 17/7/1809). back to text

- See for example Neil McKendrick, ‘Josiah Wedgwood and the Commercialization of the Potteries’ in Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb, The Birth of a Consumer Society, London, Europa, 1982. back to text

- Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, Penguin, UK, 1994 (1899). Online at: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/VEBLEN/veb_toc.html back to text

- SRRO 1066/95 (11/11/1812 – 22/12/1812). back to text

- SRRO 1066/65 (23/7/1805 – 9/11/1805). back to text

- Marcia Pointon, ‘Quakerism and Visual Culture 1650-1800’ in Art History, vol.20, No.3 Sept.1997, p.423. back to text

- Pointon ‘Quakerism and Visual Culture’, p.418. back to text

- 1714 tract in Braithwaite The Second Period of Quakerism 1919, cited in James Walvin, The Quakers, Money & Morals, London, 1997, p.35. back to text

- Postscript to Clarkson, Containing Some Observations on the Strongly Marked Distinctness of the Principles and Testimonies of the People called Quakers, anon, London 1807. It is possible that Thomas Clarkson was the author. back to text

- SRRO 1066/14 (5/12/1792 – 17/3/1793). back to text

- SRRO 1066/14 (5/12/1792 – 17/3/1793). back to text

- SRRO 1066/14 (5/12/1792 – 17/3/1793). back to text

- ‘I wish you would show the pyramid flower pots to Dr Fothergill’s sister, and consult her upon them, & if she approves of them, suppose you present her with one; it might not be lost.’ Wedgwood to Bentley June 2, 1770. In Meteyard, Eliza The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Hurst and Blackett, London, 1865, Vols. 1 & II, Vol. II, p.155. Dr Fothergill was a Quaker scientist who corresponded with Wedgwood and provided him with a useful recipe for a copper/gold glaze. Meteyard, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol. II, p.408. back to text

- Wedgwood to Bentley February 23, 1769. Meteyard, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol. II, p. 133. Emphasis in the original. Wedgwood’s close circle included many significant individuals who were not interested in emulating the aristocracy, such as Joseph Priestly – a Unitarian – to whom he paid a retainer in the hope that he would discover a method of ‘gilding by Electricity.’ Letter to Bentley, March 2, 1767. In Meteyard, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol. I, p.465. Wedgwood himself was a Socinian, a variation of Unitarianism. back to text

- SRRO 1066/25 (28/1/1794 – 21/3/1794). Although Katherine Plymley did not begin keeping diaries until 1791, her habit of writing study notebooks began at least ten years earlier. back to text

- On meeting Sir John Sinclair, who established the National Board of Agriculture, she wrote: ‘… his countenance interesting & handsome, his complexion fair & remarkably mild blue eyes, yet full of intelligence – I am almost indignant that an enemy to the abolition shou’d have such a countenance.’ SRRO 567/5/5/1/9 Journey to London 2nd. It is perhaps ironic that Sinclair was instrumental in the publication of Joseph Plymley’s 1803 Report on the Agriculture of Shropshire. back to text

- See Meteyard The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol II, p. 565; also Ann Finer, and George Savage, (editors) The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood London 1965, p.309-311. A letter from Wedgwood to Joseph Plymley dated July 2nd 1791 suggests that they discussed the distribution of pamphlets and the efficacy of petitioning parliament. Wedgwood felt that slavery ‘stigmatised’ the ‘national character’ by ‘injustice and murder.’ Wedgwood Museum paper archive, Keele University, document 18998-26. back to text

- SRRO 1066/1 (20/10/1791 – 21/10/1791). back to text

- In the preface the author recounted his efforts to persuade an audience to give up sugar, recalling the effect when ‘… one or two of the female part of the company’ requested ‘a short account of the process of making it ... and as he drew near the close of his narrative … he could easily perceive an alteration in the complexion of one of his fair hearers; and as he proceeded, knit Brows, distorted Features, and disgusted Emotions, were visible in all their countenances; till one unable to stand it any longer, exclaimed with the most determined resolution, “Well! I'll never eat another bit of Sugar so long as I live.”’ A Second Address to the People of Great Britain containing a New, and most powerful Argument to Abstain from the use of West India Sugar anon, W. Gillman Rochester. Preface. A diary entry of 5/3/1792 – 20/3/1792 clearly indicates that Katherine Plymley was familiar with this pamphlet. back to text

- 'My brother desir'd Mr Eddowes to order 500 – his family have left off the use of Sugar &Co. – The little people were the first to wish it. – ' SRRO 1066/4 (30/10/1791 – 9/2/1792). The term 'little people' refers to children. Katherine Plymley was optimistic about the campaign: ‘We have lately heard of many families in this neighbourhood who have left off the use of Sugar’ SRRO 1066/7 (5/3/1792 – 20/3/1792). See http://abolition.e2bn.org/abolition_view.php?id=33&expand=1 for a full transcript of Wright’s notice. back to text

- SRRO 1066/1 (20/10/1791 – 21/10/1791). back to text

- SRRO 1066/28 (14/7/1794 – 1/12/1794). back to text

- SRRO 1066/1 (20/10/1791 – 21/10/1791). back to text

- In Katherine Plymley’s opinion, the aristocracy had a duty to ensure the well-being of those who depended upon them. It did not necessarily fulfil this duty however, and she regarded those industrialists who displayed a stronger sense of social responsibility as more suitable leaders. back to text

- According to Thomas Clarkson, Coalbrookdale was ‘peculiarly fitted for the habitation of the Quakers’, being removed from the frivolity of urban life. Thomas Clarkson MA A Portrait of Quakerism etc. London 1807, p.51. See also p.62-67 on various professions and their suitability for the Quaker. Katherine Plymley’s perception of Quakerism was strongly influenced by Clarkson’s account, which she read in manuscript: ‘He greatly admires them without adopting their opinions...’ SRRO 1066/64 (11/4/1805 – 23/7/1805) continued in SRRO 1066/65 (23/7/1805 – 9/11/1805) See Raistrick, Arthur Quakers in Science and Industry Newton Abbot, Devon 1968, p.338-339 on Quaker 'Advices on Trade' and on Quaker attitudes to social responsibilities in general. back to text

- Raistrick Quakers in Science and Industry p.143. back to text

- ‘I think it perfectly possible to improve men in their turn of mind, by giving them proprieties in and about their habitations, they may not have thought of, or desired ...’ (Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.113-116). See also p.315 on wage rates; see also Raistrick Quakers in Science and Industry p.143. back to text

- ‘His name will add an interest and value to the communication, in the opinion of all those who have the pleasure of knowing him.’ (Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.47 & p.53). Richard Reynolds had a famous collection of fossils and minerals; he ‘offered rewards to his miners for bringing him fossils, and was always ready to talk about geology with them.’ Trinder, Barrie The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire, Phillimore, Chichester 1981, p.117. back to text

- SRRO 1066/27 (25/5/1794 – 14/7/ 1794). The Ironbridge Inn is still standing – mere yards from the bridge itself. It is likely that the visit involved information gathering connected with Joseph Plymley’s General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire. Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.138. See also Trinder The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire p.45. back to text

- The ‘Rotunda’ was built in the classical style with seven pillars; it contained a moveable seat, which could be turned to face in any direction and looked something like an iron bandstand. '...being the segment of a circle, fastened in the centre by a pin, and moves upon three wheels, running upon a circular wooden ring and easily moved in any direction forming a screen to the wind.' See Stamper, Paul Historic Parks and Gardens of Shropshire Shropshire County Council 1996, p.71. back to text

- See Stamper Historic Parks and Gardens of Shropshire for many examples. back to text

- Stamper Historic Parks and Gardens of Shropshire p.71. back to text

- See Godden, Geoffrey A., F.R.S.A. Coalport and Coalbrookdale Porcelains Herbert Jenkins, London 1970; esp. p51-5. China would have been transported by river and sea to London. back to text

- Godden, Coalport and Coalbrookdale Porcelains p.51-55. back to text

- Opinions are divided on this point. Gaye Blake-Roberts points out that following the visit of the Prince and Princess of Orange to Coalport in 1796 a visit to the China manufactory had become fashionable. (Personal communication 31/3/98.) On the whole though, my reading of Katherine Plymley dissuades me from ascribing her behaviour, or that of close family members, to a conventional quest for fashionableness. I am grateful to Ms Blake-Roberts, curator of the Coalport archive at the Wedgwood Museum, Barlaston, for information and discussion on this point. back to text

- SRRO 1066/102 (18/3/1814 – 11/5/1814). back to text

- Randall, John History of Madeley Wrekin Echo Office, Madeley 1880, p.199. back to text

- Samuel Simpson The Agreeable Historian or the Compleat English Traveller (1746). In Trinder ‘The Most Extraordinary District in the World’ Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale; An anthology of visitors’ impressions of Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale and the Shropshire Coalfield Phillimore, Chichester 1988 (1977) p.16. back to text

- Telford (report dated 1800) in Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.284-315. Telford estimated that the Coalport china factory employed about 250 people. He was another of those whose success in life was applauded by Katherine Plymley: ‘Mr Telford is a man I highly respect. Born of poor parents in the shire of Dumfries, brought up a common working mason, he has by uncommon genius & by unwearied industry raised himself to be an excellent architect & a most intelligent & enlightened man ... what he procures by his merit & Industry he bestows most benevolently, liberally: frugal in his own expences, he can do more for others & what he does he does chearfully.’ SRRO 1066/20 (16/10/1793 – 9/11/1793). back to text

- Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.341. back to text

- Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.xii. He was writing in the years leading up to 1803, at the time when the relationship between the Caughley and Coalport china works was very complex. He also mentions a traditional rural pottery producing coarse earthenware at nearby Broseley, which probably specialised in roof tiles, and another 'manufacture of earthenware, in imitation of that made at Etruria, and called the Queen's, or Wedgwood's ware.' This may have been a factory run by Bradley. Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.341. back to text

- Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.341. back to text

- Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.101. back to text

- Plymley A General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire p.99. back to text

- Richards, Sarah Eighteenth Century Ceramics; Products for a civilised society Manchester: Manchester University Press 1999, p.127. back to text

- SRRO 1066/98 (22/3/1813-13/4/1813). A ‘Simnel’ is a type of cake. back to text

- SRRO 1066/98 (22/3/1813-13/4/1813). back to text

- Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace, Consuming Subjects, New York, Columbia University, 1997, p.25. The style of the tea ceremony was subject to changes in fashion. There was a competitive element in this. The Ladies Magazine, for example, defended English tea-taking against a perceived slur perpetrated by the editor of the Journal des Modes who had claimed that Parisian tea parties were 'much more elegant'. See The Ladies Magazine, London 1820, p.100. See also Emmerson, Robin British Teapots & Tea Drinking HMSO London 1992 chapter 2: The British Tea Ceremony. back to text

- SRRO 1066/87 (29/6/1811 – 5/12/1811). Many of the Plymley social gatherings involved figures from the legal professions. Joseph Plymley was a magistrate and his two eldest sons took up legal careers. back to text

- See Dahn, Jo ‘Mrs Delany and Ceramics in the Objectscape’ in Interpreting Ceramics, vol.1 (2000). back to text

- SRRO 1066/40 Memoirs of my Father 2nd. Their mother died in 1779, when Katherine was 21. back to text

- Vincentelli, Moira Women and Ceramics, Gendered Vessels, Manchester University Press, 2000, p.113. back to text

- SRRO 1066/83 (24/8/1810 – 19/10/1810). back to text

- SRRO 1066/83 (24/8/1810 – 19/10/1810). back to text

- SRRO 567/5/5/1/12 Jurney to London 5th 1796. Christie’s auctions began at midday; in the mornings the rooms functioned much like a public gallery. There is no suggestion in Katherine Plymley’s account that she intended to buy any of the ceramics she saw. An interest in botany was considered eminently suitable for women and Katherine and Ann Plymley were both expert flower painters, as can be seen in Katherine’s entomological studies, where insects are shown with the plants on which they fed. Her expertise – which she regarded as scientific and was keen to distinguish from notions of upper-class feminine dilettantism – must have informed her appreciation of the ‘fine china’ at Christies. back to text

- A Catalogue of a Most Valuable and Superb Assemblage of French Porcelane etc. Christie’s 14th April 1796. I am grateful to Estelle Gittins, assistant archivist, Christie’s, London, for discussion on this subject. back to text

- I am grateful to Ruth Denison, curator of the museum at Coalport, for discussion regarding the china designs approximating to this diary entry when I first researched these diary entries. I am also very grateful to the current curator of the Coalport China Museum, Sophie Heath, for further recent discussion and for her generosity in accommodating my urge to handle ceramics approximating to Katherine Plymley’s account. back to text

- Marcia Pointon, Strategies for Showing; Women, Possession, and Representation in English Visual Culture 1665-1800, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.9. back to text

- SRRO 1066/104 (21/7/1814 – 9/11/1814). Mrs Panton Corbett was in her ‘Sunday best’ to take the collection as the congregation filed out of church: 'she gracefully & pleasedly curtsied as each donation was put upon her plate ... back to text

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

Bibliography

Archives

Shropshire Research and Record Office (SRRO).

Corbett of Longnor archive: documents relating to Katherine Plymley.

Wedgwood Museum paper archive, Keele University.

Document 18998-26 letter from Wedgwood to Joseph Plymley.Published sources, pre-twentieth century

Anon, Postscript to Clarkson, containing some observations on the strongly marked distinctness of the principles and testimonies of the people called Quakers, London, 1807.

Bolton, Henry Carrington (1843-1903). The Lunar Society of Birmingham, New York, 1890.

Clarkson, Thomas MA. A Portrait of Quakerism, London, 1807.

Llanover, Lady (editor). The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville Mrs Delany 6 Vols: I-II. Richard Bentley, London, 1861; Vols. IV-VI Richard Bentley, London 1862.

Meteyard, Eliza. The Life of Josiah Wedgwood, Vols. I and II, Hurst and Blackett, London, 1865.

Plymley, Joseph. General View of the Agriculture of Shropshire with Observations, drawn up for the consideration of The Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, B. McMillan, London, 1803.

Priestly, Joseph. An Account of the Rise of Arian and Socinian Doctrines, London, 1794.

Randall, John. History of Madeley including Ironbridge, coalbrookdale, and coalport, from the earliest times to the present with notes of Remarkable Events, inventions, and Phenomena, Manufactures &C Wrekin Echo Office, Madeley, Salop 1880.

Randolph, Francis Scriptural Revision of Socinian Arguments, Bath, 1792.

A Catalogue of a Most Valuable and Superb Assemblage of French Porcelane etc. Christie’s, 14th April 1796.

An Address to the Inhabitants of Europe on the Iniquity of the Slave Trade, London, 1822

A Second Address to the People of Great Britain containing a New, and most powerful Argument to Abstain from the use of West India Sugar, By an eye witness to the facts related, W. Gillman, Rochester, 1792.Latter day published sources: books

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste Routledge, London, 1984. 1st pub. 1979.

Brewer, John. The Pleasures of the Imagination, Fontana, London, 1997.

Brewer, John and Porter, Roy (editors). Consumption and the World of Goods, Routledge, London, 1994.

Campbell, Colin. The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism, Blackwell, Oxford, 1989.

Davidoff, Leonore and Hall, Catherine. Family Fortunes, Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850, Hutchinson, London, 1987.

Dawson, Aileen. French Porcelain A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection, British Museum Press, London, 1994.

Douglas, Mary and Isherwood, Baron. The World of Goods, Towards an Anthropology of Consumption, Penguin, 1978.

Emmerson, Robin. British Teapots & Tea Drinking, HMSO London, 1992.

Finer, Ann and Savage, George (editors). The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood, Cory, Adams and Mackay, London, 1965.

Godden, Geoffrey A., F.R.S.A. Caughley and Worcester Porcelain 1775-1800, New York and Washington, 1969.

Godden, Geoffrey A., F.R.S.A. Coalport and Coalbrookdale Porcelains, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1970

Holt, Anne Durning. A Life of Joseph Priestly, Oxford University Press, London, 1931.

Kowaleski-Wallace, Elizabeth Consuming Subjects, Columbia University, New York, 1997.

Mosco, Marilena. L’Immagine Riflessa, Firenze, Museo degli Argenti, 1997, p.93.

McKendrick, Neil, Brewer, John, Plumb, J.H. The Birth of a Consumer Society, Europa, London, 1982.

Messenger, Michael Caughley and Coalport Porcelain in Clive House Museum Shrewsbury, London, 1976.

Pointon, Marcia Strategies for Showing; Women, Possession and Representation in English Visual Culture 1665-1800, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Raistrick, Arthur. Quakers in Science and Industry, Newton Abbot, Devon, 1968.

Richards, Sarah. Eighteenth Century Ceramics, Manchester University, 1999.

Schofield, Robert E. The Lunar Society of Birmingham, a social history of provincial science and industry in eighteenth century England, Oxford, 1963.

Smith, Stuart. A View from the Ironbridge, Ironbridge Gorge Museums Trust, 1979.

Stamper, Paul. Historic Parks and Gardens of Shropshire, Shropshire County Council, 1996.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade, Macmillan, London, 1998.

Strangman, Paul. The Lunar Society of Birmingham, London, 1966.

Trinder, Barrie. The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire, Phillimore, Chichester, 1981.

Trinder, Barrie, ‘The Most Extraordinary District in the World’ Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale; An anthology of visitors’ impressions of Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale and the Shropshire Coalfield Phillimore, Chichester, 1988, (1977).

Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class, Penguin, London, 1994, (1899).

Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman’s Daughter, Women’s Lives in Georgian England, Yale University, New Haven & London, 1998.

Vincentelli, Moira. Women and Ceramics, Gendered Vessels, Manchester University, 2000.

Weatherill, Lorna. The Pottery Trade and North Staffordshire 1660-1760, Manchester University, 1971.

Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain 1660-1760, Routledge, London, 1988.

Latter day publications: journals

Guyatt, Mary ‘The Wedgwood Slave Medallion: Values in Eighteenth-century Design’ in Journal of Design History vol. 13, no.2, 2000; p.93-105.

Pointon. ‘Quakerism and Visual Culture 1650-1800’ in Art History, vol.20, no.3, Sept. 1997; pp.397-431.

Reily, John. ‘Shenstone’s Walks: The Genesis of the Leasowes’, Apollo, 110, Sept. 1976; pp.202-209.

Styles, John. ‘Design for Large-Scale Production in Eighteenth-Century Britain’ in The Oxford Art Journal, 11/2/1988.

Latter day publications: catalogues

Smith, Stuart B. A View from the Ironbridge, RA, 1979.

Ironbridge: a World Heritage Site, Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, 1996.Conference papers

Torrens, H.S. Mineral Exploitation and ‘Revolution’ in the Shropshire Region 1650-1850 at ‘Science for Life’ at Keele University 29/8/93 – 3/9/93.

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated

Ceramics in the West Midlands in the Late 18th Century • Issue 11