Interpreting Ceramics | issue 11 | 2009

Articles & Reviews

|

National Identity and the Problem of Style in the Post-War British Ceramic Industry

Graham McLaren

| Contents | Home |

|

by Jo Dahn National Identity and the Problem of Style in the Post-War British Ceramic Industry by Graham McLaren Pushing the Boundaries of Ceramic Art Tradition in Nigeria: Notes on the ‘Suyascape’ Project by Ozioma Onuzulike Ceramics Without the Ceramics: Material Exploration in New Territories by Jane Webb Studio Pottery in Britain 1900-2000, book review by Graham McLaren Zelli Porcelain Award 2009, Competition review by Peter Holmes |

| NB. A Word document is available to download at the end of each article. |

Abstract

This paper argues that the search for an identifiably and quantifiably British style in British ceramics formed a key aspect of the post-war reconstruction of its pottery industry. It seeks to demonstrate that this process was as much about sweeping away internal structures and the boundaries that acted as barriers to change as it was about a reaction to the economic necessities of the 1950s and early 1960s. The paper will show that in order to understand this process we must understand the mechanisms by which the pottery industry evaluated the role of design within manufacturing and marketing processes. It argues that changing systems of communication, both within the industry and between industry and those planning its future, were key facilitators of this process.

Key words: industry, war, utility, New Look, tableware, Scandinavia, Staffordshire

‘... if we can openly say: This idea is English, then we shall keep and win many markets by the one quality which precludes competition ... our way, our national way.’ (original emphasis) 1

The language used to articulate hopes and fears for the future by the British pottery industry from the mid 1940s onwards has to be understood as part of a debate that had already raged for many years. The ten years before the war had been something of a rollercoaster ride for the British pottery industry, not least in economic terms. The ‘answers’ to the Depression years had brought new pressures to bear on an industry well known for its insularity, its paternalistic management structures and its conservatism. These forces for change were felt particularly sharply in relation to the design process and to arguments surrounding an appropriate aesthetic for the future of British ceramics. Style and design had always been the most visible aspect of the industry and the one upon which it was most keenly judged.

The lines of communication that alerted manufacturers to issues like these were well established by the years immediately before the war. Industrial and trade organisations, most prominently the British Pottery Manufacturers Federation (BPMF) provided forums where manufacturers could discuss issues of concern face-to-face, whilst trade exhibitions such as the annual British Industries Fair (BIF) offered an opportunity to gauge trends in design terms. In reality there is an argument for saying that both of these acted more as brakes to change than providing catalysts for it. Industrial organisations seem instead to have been spaces where the supremacy of the ‘traditional’ was reaffirmed as at the heart not just of the manufacturing process, but of the very identity of the industry itself, as Sir Henry Cunyngham’s (1918) advice on issues of style and demand suggests:

If the London East Enders want roses on their plates, give them roses - only try and make them lovely roses. If pretty children's faces peep out from among the roses so much the better.2

More fruitful in terms of establishing dialogue was the role of print media, and in particular the trade press. The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review had been the pre-eminent organ of the industry from the early 1870s, but by the 1930s it had competitors such as Pottery and Glass. The approach of the Pottery Gazette, almost from its inception, had been to funnel news and advice on national and (crucially) international trends in economic, cultural and design terms into the industry through its pages, and to communicate and even initiate debate on key issues within its pages.

The outlook of the trade press had gradually changed and evolved during the first thirty years of the twentieth century though. Most significantly there had been a re-focusing of editorial attention away from the relationship of the manufacturer to his market. This had been a vital task for the Pottery Gazette during the early years of its production, with editorial content ‘explaining’ often distant markets to the pottery manufacturers, and retailers in those markets learning more of the ware that the British industry offered via richly illustrated advertisement sections and editorial reviews. By the last years of the 19th century however, improved travel and increasingly sophisticated market structures meant that the mediation provided by the press was being replaced by face-to-face contact, a phenomenon noted (1893) by the short-lived trade journal The Potter:

The manner pottery manufacturers have to pay court to the ‘American’ buyers who come over to North Staffordshire to make their own terms with the makers, is very different to what it was in the old days. The gentleman from the States takes rooms at the North Stafford Hotel, Stoke, and he soon lets it be known that he is willing for anxious sellers to lay their treasures at his feet at his own price.3

By the 1930s the focus of the trade press was far more on providing a context for design and production. With this shift came a tacit understanding that both the manufacturer and the retailer were elements within a larger production/consumption cycle.

The space created by these changes was one that demanded a greater contextualisation of the pottery industry and its relationship with larger industrial, social and cultural issues. The battle for this space raged before, during and after the Second World War. It not only set the tone and context for the future development of the industry in terms of the style and design of its products, but brought to the fore a new class of critics and commentators whose role extended beyond rhetoric, becoming substantial and significant forces for change.

Significant amongst these were the writers who had their roots in connoisseurship. They comforted manufacturers, and the retailers who depended upon them by illuminating a readily delineable and separate tradition for British ceramics extending back to medieval times. This approach provided manufacturers with a key underpinning to their belief in the ‘traditional’ as being central to the industry, and also a demonstrable scale of technical and stylistic evolution against which to judge the success or otherwise of their efforts.

By the early 1940s this approach was receiving official sponsorship via war-time publications. These were designed to give the public a clear understanding of the role of manufacturing (in this case of pottery) in British life. Medieval products were highlighted in this context, being shown to possess ‘... the everyday characteristics of the people themselves, commonsense and humour ...4 fourteenth and fifteenth century pots ‘...are robust, generous and hearty and seem to be typical of Chaucer's England’5 and English slipware and saltglaze types of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have ‘... a peculiar wholesomeness, comparable to that of cottage bread ...’6 (Fig.1)

|

Fig 1. An example of the ware that British modernists approved of, a bag-shaped earthenware jug dating from the 14th century. |

This view of the past was by no means uncontested. An example of attitudes that used the same historical data to arrive at very different conclusions can be seen in the work of Bernard Rackham and Herbert Read. Their English Pottery of 1924 extolled the hitherto unrealised virtues of British medieval pottery which ‘...are almost invariably well balanced and effective’7 but, crucially, they emphasise that these wares ‘... show indeed a dignity which is wanting in most of the later wares.’8

How do we explain Rackham and Read’s view of the ceramic products of the past as a rebuke to the contemporary industry rather than an affirmation of it? Bernard Rackham was a London-based museum keeper and connoisseur whilst Herbert Read was a left-leaning critic who was to become a key interpreter of continental modernist tendencies in art and design for the British public. Their approach can be allied to the writings of the delineators of tradition in the larger design sense. Rackham and Read's assertion for instance that the quality of 14th century slipware, excelling, they believe, even those of the 17th and 18th centuries is due to ‘... the use of a narrow range of clay pigments, a simple design serving only to emphasise form, and the avoidance of any confusion between the simple and the crude ... 9 correlates with John Gloag's later (1947) vision of the medieval craftsman who had ‘... that deep affectionate sympathy for materials, that sense of apt selection and gay orderliness in the forms of embellishment, which are inseparable ingredients of the English tradition of design.’10

Rackham and Read are examples of writers who rose above the narrow confines of discourse within the industry, recognising and analysing larger contexts for its production. Key features of this group of critics included their largely London base and the fact that they questioned the whole basis of a coherent stylistic tradition for the pottery industry, seeing instead the rampant eclecticism and historicism of contemporary production as a problem for it rather than a selling point. Their writing on this issue was largely published outside the trade press but was very fully reported within it.

The views of this group had been receiving semi-official sanction through the work of organisations such as the Design in Industries Association (DIA) from the mid 1930s. This organisation highlighted the reliance of the pottery industry on largely nineteenth century decorative traditions through its journal Art and Industry. Overt criticism concealed dangers though, not least the creation of a 'very real hostility'11 felt by the pottery industry towards this largely London based 'design establishment'. Indeed, a key critic within the modernising tendency, Nikolaus Pevsner, had warned in his seminal 1937 Enquiry into Industrial Art in England against a ridiculing of nostalgia and decoration, because this '... can only deter people from studying the modern style, and from trying to appreciate it ...'12

The industry would have probably been totally hostile to such pressures for change had it not been for the writing of certain individuals who acted as bridges between industry and government. Of these, the roles of Gordon Forsyth and Harry Trethowan stand out as key to understanding communication systems within the pottery industry during the years spanning the Second World War. Forsyth, Superintendent of Art Instruction in Stoke-on-Trent from 1919 to 1945 was a highly respected figure in the industry and well known nationally as someone who wished to raise the standard of ceramic design. Harry Trethowan, managing director of Heal's Wholesale and Export Limited and a former President of the China and Glass Retailers' Association was a very real influence on the industry from that side of the trade. As a Buyer of ceramics of long standing he was regarded as a man well able to gauge the taste of the buying public, and was therefore held in high regard by the industry. Both were known nationally as well as in the pottery industry, frequently writing articles for the trade press and appearing on various design related committees. They also shared some (but by no means all) of the interests of the modernisers. In particular their view that the quality of basic shape and form was the overwhelming ceramic design issue acted as a valuable point of linkage between their beliefs and those of the ‘design establishment’.

During the war years their interest and their work was concentrated largely on the effect of the Utility scheme upon the Staffordshire pottery industry. The Utility scheme was a nationwide plan to provide the country with basic, well designed household furnishings during the war years, concentrating on the needs of newly wed couple and those who had been bombed out of their homes. I have shown elsewhere13 that the writings of Trethowan and Forsyth played a key role in supporting government policy during the early years of the scheme, emphasising the policy back to the industry through the trade press as a 'new start' that would have the effect of 'cleansing' it of its historicist tendencies. Early articles by both men used terms like 'chastity', 'virginity', 'cleanliness', 'morality', and 'new growth' to describe the potential of the scheme:

This day of austerity, in every phase of its rationed life, proves to us that hitherto we were wasteful and improvident-wasteful in every section of our life-and the things of which we have been deprived create no real hardship, and life is not really inwardly or outwardly defrauded or constrained. We have in all spheres time to estimate life's true values ... how are we going to assess the values, and are we going to be the better for having passed through a fire that refines.14

This approach was significant because the government had to overcome industrial opposition to Utility ceramics that began as soon as the scheme was mooted. The manufacturers, hoping to preserve as much of their industry as possible, proposed an approach that would have kept planned factory amalgamations and closures (a process known as 'concentration') to a minimum, but which was rejected out of hand by the Board of Trade in favour of a drastic reduction of the industry. Trethowan and Forsyth also had to explain the logic behind Utility as the scheme quickly opened divisions between concentrated manufacturers and the 'nucleus' firms that had been allowed to continue production. These were predominantly the fine china firms with established records of export achievement - and exporting to win hard currency (particularly American Dollars) was a central plank of government economic policy during the early years of the war. Some believed that they saw duplicity between government and the nucleus firms; and although the argument in favour of export earnings eventually proved unassailable it did pose an early and severe problem for those advocating modern design. The output of nucleus firms was overwhelmingly traditional in both form and decoration, with a heavy emphasis on crafts skills that had historically found a ready market in North America. By comparison the competitive earthenware and stoneware sectors of the industry, specialising in low to mid-priced ware bore the brunt of concentration. Ironically, this was also the sector of the industry that had been most amenable to change in design terms, particularly in accepting some of the lessons presented by continental modernism.

By 1945 the leading modernist writers in Britain, critics like Misha Black, Nickolaus Pevsner and Herbert Read could find much to praise in the purifying role of the Utility scheme within British manufacturing industry generally, but were particularly positive about its effect upon ceramic design:

the utility designs for tableware has probably reached the highest standard of any utility products; and these have been produced naturally within the industries themselves without any of the ‘sweat and toil’ which unavailingly has been expended in many other fields.15

Laudatory remarks like these mask the fact that the confidence expressed in the scheme by key interpreters of it like Harry Trethowan and Gordon Forsyth had been lost by this time. The concentration of the industry had quickly imposed a functionalism far more austere than even the modernising tendency could have hoped for, leading many manufacturers to bracket the stylistic elements of modernism with state control during the war and also (their greatest fear) after it. This general antagonism meant that although the Utility scheme continued to have an influence on ceramic design through into the early 1950s, the argument for it as a viable aesthetic for the post-war world was effectively lost by the end of the war. The critical atmosphere in the pottery trade press of the late war years was one that had moved from an emphasis on the necessities of war and of survival to a questioning of what the future would hold for the British industry. Core to the debate was the issue of national identity. The war had shown that the 'traditional' could earn export income, whilst Forsyth's initial enthusiasm for the Utility scheme had by 1944 turned to writing disparagingly of the ‘... Elephantine cups, with clogs on for handles’ that the scheme produced.16 (Fig.2) Initially then, the debate seemed to lean towards the pre-war eclecticism and figurative decoration generally identified by the pottery industry’s friends and foes as traditional to it.

|

Fig 2. Examples of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Utility ware as seen by Gordon Forsyth. Planning Prosperity’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review May 1943. |

The reasons why this approach did not entirely win the day are varied and complex. One of the most powerful was a quick realisation by the industry that things were not going to be the same in the post-war world as they had been in the 1930s. Most noticeable is the changing attitude towards the consumer during the early post-war years. Harry Trethowan's 1951 comments that ‘the consumer is inarticulate’17 and that ‘there is no public taste to cater for ... it buys what it sees ...18 are among the last of their type in the industry's trade journals.

In its place the lack of concrete knowledge of what the post-war market would require, together with the vague fear, increasingly expressed, that ‘... the masses in a generation or so are going to be as discriminating as the connoisseur of today...’19 led designers, manufacturers and government funded organisations like the Council of Industrial Design (COID) into a struggle to develop an aesthetic which could embody essentially 'British' characteristics (seen even then as a key selling point in export markets) alongside a 'modern' feel.

Against this backdrop the focus of critical debate on the nature of ‘Britishness’ in ceramic design soon shifted towards the design community. During the early years of the war writing on the heritage of the industry had located it not so much in the objects themselves as in the men and women who designed and made them. Much was made of the irretrievable loss of skills within the pottery industry due to conscription. This was despite the fact that designers in general (and particularly those who worked 'in house') had never been accorded high status within it.

Matters came to a head immediately after the war through the agency of the Britain Can Make It exhibition of 1946. The reaction to the exhibition by the trade press was highly equivocal. The feeling that the exhibition selection committee had chosen ‘... a limited collection of pottery which will appeal to an even more limited section of the public’20 was shared by many in Stoke-on-Trent who saw the final display as reflecting the broadly pro-modern and anti-tradition views of the London based Establishment.

The early post-war years therefore saw writing emanating from Staffordshire identifying Whitehall in general and the government funded Council of Industrial Design in particular as conduits for dangerous foreign ideas. Writing under the nom de plume of ‘Argus’ the editor of Ceramics, a trade journal with a distinct emphasis on technical issues summed up the views of many in the industry towards the COID:

This Council of Industrial Design has for quite a period been a neat little nest where the architects and their confreres have been able to browse in safety and security. It has not, and never will, give anything like commensurate value for its cost … the Council of Industrial Design does not want pruning: It wants cutting out by its roots!21

The 1952 editorial that contains this attack is helpful in that it serves to demonstrate that the emphasis for the pottery industry of being under attack from ‘the foreign’ in terms of design aesthetics was becoming much more focused. To Argus the attack was coming from the Scandinavian form of modernism, promoted in Britain via the COID and identifiable in the selection policies for first the Britain Can Make It exhibition and then the Festival of Britain (1951). For Argus the link between the design aesthetic, government control and society was clear. He saw the Scandinavian approach to modernity as a system that ‘… has converted Sweden into a nation of flat-dwellers, forever craving after some sort of plant life to cultivate and having to be content with some creeper on the wall or a window box looking out into the street.’22 He links the aesthetic with a sapping of vigour from the population. Through this process Argus sees Swedish women becoming ‘… dowdy and frumpish’ they ‘… neither wash their hands nor powder their noses from the time they enter the office in the morning till they go home in the evening.’23 For Swedish men the penalty for the pursuit of modernity was to be branded as effeminate:

There are no public houses or bars and you cannot even buy a humble glass of beer … One of the most depressing sights is to see a crowd of young men sitting outside a wayside café fresh from a game or a country walk sipping away at small glasses of lemonade or milk.24

In summing up the Scandinavian modern aesthetic for his audience, ‘we would call Swedish furniture – Utility furniture’25 Argus makes a telling link between this brand of modernity, the design intervention of the British government during the war, and the potential danger of future moral and social decay as well as foreign competition.

Whilst Scandinavian modernism was seen by trade press articles such as this to hold out the threat of a homogenised, socialist future, challenges to the Englishness of the English aesthetic were perceived as coming from individuals too. Prime amongst these during the early post-war years was the work and influence of Pablo Picasso. (Fig. 3)

|

Fig 3. An image circulated to schools and colleges by the Council of Industrial Design in 1948, with the caption: ‘Now fortunately outmoded but still to be seen, and avoided. The unfunctional handle and the decoration provide a useful cautionary study.’ |

Exhibited in Stoke-on-Trent in 1950 as a government sponsored touring exhibition, Picasso's work in pottery caused a local furore. The industrial potters saw it as the antithesis of their heritage of careful workmanship and slow design development. Their attitude towards the ‘... chaotic mysticism of the Picasso School’26 meant that the artist’s name joined terms like 'Jazz', 'Cinema', and 'Futurist' as terms of abuse to describe modernist thinking generally. J W Wadsworth, Art Director of Minton's was asked for example by the Pottery Gazette (1951) to suggest what type of design was likely to be required in the next decade. He was firm in the belief that ‘... the futurist variety - the product of lazy people trying to set lazy fashions ... the Picasso type ... will never have a future in pottery…27

This attitude was not limited to the industrial producer. It is one of the ironies of post-war reconstruction in Britain that these ‘threats’ are mirrored in writing produced by both industrial and studio potters. Industry and the studio pottery movement had for much of the twentieth century seen themselves as at opposite ends of the craft. To the craft potters, the ideals of the Modern Movement saw a future of large, collective organisations in which the machine dominated and there was no room for the individual craftsman, whilst the rampant, fine art basis for the individualism of Picasso’s work shocked and unsettled studio potters like Bernard Leach, who saw Picasso’s influence as ‘… too much from above to below, from the easel to the clay. Picasso is a great and inventive artist, but he is not a potter and his effect on potters has been disastrous.’28

Against this background writers sought parallels in the history of the industry. Comparisons were made for example between the disruption of the world of the early potter by industrialisation, and Britain’s situation. The language used in writing on the subject is that of the good, the pure, and the 'British' being challenged and threatened by outsiders. A war-time example is provided by Gordon Forsyth's daughter Moira, who produced an influential government sponsored report (1943) on reconstruction in the pottery industry that gives a particularly vivid example of this process. Considering the future of the industry in the context of its past, she puts the break leading to the eventual loss of the medieval tradition as the arrival of the Dutch Elers brothers in the Staffordshire area during the 1670s. They were ‘foreigners’ to the district who ‘... conducted their work in great secrecy, apart from the general community’ and ‘thought in terms of metal rather than clay ...’29

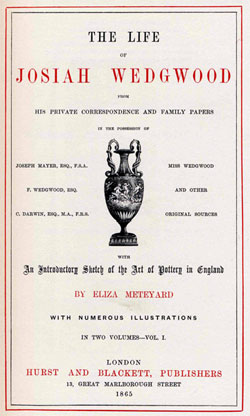

Out of this she developed a framework for understanding the decline of natural 'good taste' in pottery design over the previous two centuries by ascribing it to the pernicious effect of foreign influence. (Fig.4) Hence Josiah Wedgwood is accused of introducing Neo-classicism into the pottery industry as ‘... a conception foreign to the natural development of the craft’30 and an outside artist, Flaxman, who ‘... understood nothing of the processes or of the materials in which his work was reproduced ...’31 thinking ‘... not in terms of pottery, but of sculpture ...’32. Similarly, the excessively florid style of the nineteenth century was blamed by Forsyth on the influx of decorators and modellers ‘... from Sevres and elsewhere who sought refuge here in the Franco-Prussian war ... their idea of a design was to apply a spray of highly realistic flowers indiscriminately to any available surface ...33

|

Fig 4. Frontispiece to Eliza Meteyard’s Life of Josiah Wedgwood, London 1865. Meteyard’s Life was to have a key role in reinvigorating Wedgwood’s reputation, placing him as a key interpreter of Neoclassicism in Britain. |

The question of what made British ceramic design peculiarly 'British' echoed through the 1950s, in that the preservation of a national design identity in pottery was regarded as the best hope for the future. This attitude is apparent as late as 1957 in an argument put forward by the (unidentified) author of ‘Tradition and the Something Different’ in Pottery and Glass:

the industry will receive a challenge when the European Common Market comes into operation ... Ultimately, this should encourage countries to stick to making what they have become famous for- in other words, to make the best possible use of their traditional crafts, skills and processes - rather than to imitate popular lines from other countries. We can hope that this will lead to a happy state of affairs, of economic advantage to all.34

An emphasis on a national rather than traditional design style had other advantages. With the possible exception of the Midwinter company after 1950, the most progressive companies for design during the 1950s were 'out-potters'- firms located outside the Stoke-on-Trent area. Whilst the popular perception of traditional design in ceramics focused largely on the products of North Staffordshire, with the post-war expansion of firms such as Poole, Denby, Hornsea and in Scotland Govancroft the focus of interest in terms of contemporary design began to shift away from Stoke-on-Trent.

Perhaps the greatest change however was in the relationship of ceramics to other industries. Producers were having to face an industrial system that was no longer based on a series of essentially 'island' industries producing design in their own idiom:

It is, nowadays, becoming increasingly apparent that a link up between pottery, glass and textiles can be a valuable sales aid. Whereas before, or just after the war, the whole idea smacked of being chi-chi, it is clear that the public are growing more and more design conscious. Visible proof can be found in the crowds, purely intent on window shopping and comparing displays, who invade the big towns and cities on Saturdays. As a result, whereas before the war a fashion was prevalent mainly among richer people, today it penetrates to a greater extent down from the West End through every strata and is to be found, though sometimes vulgarised, in every suburban store.35

The new 'national' idiom would therefore have to be adaptable enough to harmonise with other design conscious industries. In this sense it was crucially different from the idea of the 'Traditional' that emphasised the past of the pottery or the furniture industries in isolation. Pottery and Glass ran a series of articles dealing with the possible integration of different materials which pointed out how developments in transfer technology laid open the way for combining and integrating decoration between different media. It also emphasised the extent to which continental firms were already capitalising on these advances, citing examples such as the links between the German firm Rosenthal and the Swedish glass company Orrefors, offering to put companies in touch with suitable 'opposites' in other materials.36

In general though the specialised trade journals struggled with the complexities of explaining this new world to their readership. Instead, a helpful starting point for understanding the form that ceramic design took is provided in the introduction to a survey entitled ‘The Potteries in Transition’ by George Ratcliffe for the government backed Design (1963). Taking as a baseline the survey of pottery design provided by events such as Britain Can Make It, the Festival of Britain, and the souvenirs produced by the industry for the Coronation in 1953, Ratcliffe noted how the ‘Britishness’ of British ceramic design had developed into a series of motifs based on a mixing of foreign influences and what he regarded as traditional design. Among these new motifs were:

- An emphasis on body material, with earthenware losing its connotations of cheapness, and generally whiter wares being produced.

- A contraction in the number of shapes and patterns available, particularly compared to the pre-war period. This lessened the emphasis on the 'give the customer what he wants' attitude which had been dominant in the industry.

- A new concentration on shape that, although moving away from specific examples, continued to use shapes with historical and national meaning. Ratcliffe cited in particular David Queensberry's shapes derived from the old milk churn form for Midwinter.37 (Fig. 5)

|

Fig 5. Tableware in Sienna pattern by Jessie Tait on Fine Shape, designed by David Queensberry for W. R. Midwinter, 1962. |

Ratcliffe's views would be dangerous evidence to take in isolation, but the early 1960s were a period of general reflection on the post-war years, and by this time there was something of a consensus in the trade as well as among outsiders. ‘Post-war British designs of new non-traditional character are selling steadily, and in most cases better than traditional designs of prewar or postwar origin’38 noted the retailer Angus G. Bell in 1962. He suggested that:

Continental travel and continental salesmanship brought us both the demand for, and the offer of (at first sight), outlandish designs ranging from almost invisible patterns on the severe white shapes of Scandinavia to the carefree riot of coloured vegetables, etc; from Italy. These things gave our minds a much needed jolt- breached, one might say, our smug, safety first, ‘reproduction’ defences, and let in the post-war British designers, backed by the COID.39

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

Notes

- J. Gloag, ‘Planning for the Future’, Art and Industry, 1941, p132. back to text

- Sir H. Cunynghame, 'communication, 31 Jan 1918' Transactions of the Ceramic Society, vol. 17, 1918, p177. back to text

- The Potter: A Journal for the Manufacturer and Retailer, vol. 1, no. 1, Sept 1893 p134.back to text

- M. Forsyth, Design in the Pottery Industry, Nuffield College Social Reconstruction Survey, October 1943 p4 back to text

- C. Sempill, English Pottery and China, London, Collins, 1946, p11. back to text

- C. Marriott, British Handicrafts, London, British Council, 1943, p34. back to text

- B. Rackham, and H. Read, English Pottery, London, EP, 1972, (reprint of 1924 edition), p11. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- J. Gloag, The English Tradition in Design, Middlesex, Penguin Books, 1947, p8. back to text

- ‘Design Week in the Potteries’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, April 1949, pp.375-376. back to text

- N Pevsner, An Enquiry into Industrial Art in England, Cambridge University Press, 1937, p.10. back to text

- G. McLaren, ‘Moving Forwards but Looking Backwards: The Dynamics of Design Change in the Early Post-War Pottery Industry’, in P.J. Maguire and J.M. Woodham, Design and Cultural Politics in Postwar Britain: The Britain Can Make It Exhibition of 1946, Leicester University Press, 1997. back to text

- H. Trethowan, ‘Utility Pottery, The Studio, February 1943, p48. back to text

- ‘Tableware in Wartime’, The Architectural Review, January 1945, pp27-28. back to text

- G. Forsyth, ‘Planning Prosperity’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, May 1944, p.262. back to text

- ‘Design Quiz No 3’, The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, May 1951, pp748-753. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- ‘A Layman Looks at Design’, The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, May 1945, pp259-261. back to text

- ‘Exhibition Forum’, Pottery and Glass, November 1946, p19. back to text

- Argus, ‘Comment’ Ceramics, vol 3, no. 36, February 1952, p454. back to text

- Ibid, p.455. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, April 1950, p521. back to text

- ‘Design Quiz No 2’, The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, April1951, pp571-575. back to text

- Bernard Leach, 'The Contemporary Studio-Potter', Pottery Quarterly, vol.5, no.18, Summer 1958, pp.43-58, p.47. Quoted in Jeffrey Jones, ‘In Search of the Picassoettes’, Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 1, 2000. back to text

- Forsyth, M Design in the Pottery Industry op.cit p.4. back to text

- Forsyth, M p10. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Forsyth, M p.9. back to text

- ‘Tradition and the Something Different’, Pottery and Glass, August 1957, pp253-254. back to text

- ‘The Link Between Pottery and Furnishings’, Pottery and Glass, May 1957, pp155-161. back to text

- ‘Pottery and Glass in Harmony’, Pottery and Glass, October 1956, pp336-340. back to text

- G. Ratcliffe, ‘The Potteries in Transition’, Design, no. 177, 1963, p48. back to text

- A G Bell, ‘Good Design or Good Seller - Can You Have Both?’ The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, September 1962, pp.1089-1093. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated

National Identity and the Problem of Style in the Post-War British Ceramic Industry • Issue 11