Interpreting Ceramics | issue 11 | 2009

Articles & Reviews

|

Pushing the Boundaries of Ceramic Art Tradition in Nigeria:

Notes on the ‘Suyascape’ Project

Ozioma Onuzulike, Lecturer in ceramics and art history, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

oziomachukwu.blogspot.com | ceramicvoice@yahoo.com

| Contents | Home |

|

by Jo Dahn National Identity and the Problem of Style in the Post-War British Ceramic Industry by Graham McLaren Pushing the Boundaries of Ceramic Art Tradition in Nigeria: Notes on the ‘Suyascape’ Project by Ozioma Onuzulike Ceramics Without the Ceramics: Material Exploration in New Territories by Jane Webb Studio Pottery in Britain 1900-2000, book review by Graham McLaren Zelli Porcelain Award 2009, Competition review by Peter Holmes |

| NB. A Word document is available to download at the end of each article. |

Abstract

This paper uses the example of my mixed media project titled ‘Suyascape’ (which draws inspiration from the West African grilled meat delicacy called ‘Suya’) to provide an insight into the kind of technical and conceptual transformations currently taking place in the contemporary Nigerian ceramic art scene. An excursion into the history of modern Nigerian ceramic art has been used to locate works in the ‘suyascape’ series in the stream of history so as to provide the right context for their appreciation.

Key words: ‘Suya’; Nok Culture; Nsukka; Nigeria

Introduction

Although a few articles have before now hinted on my work as an emerging contemporary Nigerian ceramic artist seeking to broaden his practice to include the use of non-ceramic components, there is still no detailed art historical context provided so as to situate my vision, technical approaches and conceptual strategies in the stream of contemporary Nigerian art. For example, in his article ‘Interrogating the Human Figure in Bridging the Ceramic-Sculpture Divide: Practice in Nigeria’ published in Issue 8 of Interpreting Ceramics1, a number of my works have been used by the Nigerian contemporary sculptor, Tonie Okpe, to illustrate ways by which ‘the broadening scope of hand-built ceramic craft in Nigeria includes figurative work to a greater extent now than at any time in the past’2. According to Okpe:The early Nok terracotta, for instance, demonstrates that the figure in art in Nigeria is not the exclusive preserve of sculpture or painting but is also part of the ceramic craft, despite the rich legacies and continuity and constant change occurring in traditional pottery, which in the 1950s was boosted by the immense contribution of the potter Michael Cardew at his Suleja base. The strict tradition of practice, of sculpture for sculptors and pottery for ceramicists, began to decline considerably in the late 1970s as sculptors began experimenting with ceramic methods of hand-built forms while their counterparts took an interest in producing figurative work outside of the pure dictates of sculpture. Ozioma’s work in terms of style and diversity of theme is of social relevance to Nigeria and the world.3

Before Tonie Okpe’s article, I had articulated my conceptual concerns in an essay that won a highly commended prize in Interpreting Ceramic’s Speak for Yourself Competition 2006. In her introductory comment on my essay, Jo Dahn writes:

Despite its brevity, we felt this entry conveyed a very real sense of what it might be like to make ceramics in contemporary Nigeria and were impressed by the highly moving section subtitled 'Casualties Idiom' with its lists of horrifying practices. It is a percussive, at moments frantic, piece of writing that gathers in pace, rises to a crescendo and mutates into poetry.4

My entry for that competition is an extension of an earlier article in Ceramics Technical5 that narrated my beginning and growth as an emerging Nigerian artist trained as a ceramicist at the BA and MFA levels at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. These publications so far have offered no deep insight into the context of the emergence of my line of studio inquiry in the contemporary Nigerian art scene. There is also as yet no shared knowledge on my basic technical procedure to mixed media sculptures and installations, especially concerning how I employ ceramic elements as the centre point of my works’ visual and conceptual speeches or concerns.

I have had the view that although clay as an earth material has been acclaimed the oldest media used by man to make useful vessels, it has suffered a curious kind of marginalisation in the choice of materials used by mixed-media artists over several centuries.6 In spite of clay’s possession of a very high horsepower for conveying loads of art ideas, its widespread use in the production of utilitarian vessels for domestic use appears to have drawn attention away from its expressive potentials and conceptual qualities. This is as true in Nigeria as it may be elsewhere. And this is perhaps why many art historians and writers, until recently, have not paid adequate attention to works in clay7. Just like Moira Vincentelli, I have always wondered what the ‘substantive’ difference is ‘between indigenous ceramics, folk art and fine craft’.8 Indeed in my country, Nigeria, any sincere gaze at such spectacular works as the pots excavated by Thurstan Shaw in the historic town of Igbo-Ukwu9, as well as the pots collected by Sylvia Leith-Ross for the Jos Museum,10 show a marked technical virtuosity comparable to the famous Nok terracotta sculptures, which inspired ceramic experiments by elder contemporary artists in Nigeria, especially Demas Nwoko and El Anatsui. It appears to me also that apart from modernist art writers’ apathy to works in clay, it would seem that, until recently, the use of clay for mixed-media sculptures have remained largely left out of the purview of many artists. This was the state of clay work in Nigeria in 1999 when I began to do more serious work as part of my MFA programme in ceramics at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.11 It was a certain kind of curiosity over the closed nature of clay work in Nigeria that sparked off my interest in the exploration of clay (especially earthenware clay) for mixed-media sculptures and installations in a series of projects that I call ‘Ceramics without Borders’.12

It is the aim of this paper to briefly describe and analyse one of my key projects so far, in terms of materials, technical procedure and iconography. But first, an understanding of the history of ceramic art in Nigeria is important for an appreciation of how I have sought to depart from tradition. In other words, it is useful to begin by locating my work within the historical stream of contemporary art in Nigeria. The next section of this essay does so, after which I will proceed to discuss the ‘Suyascape’ project.

Contemporary Nigerian Ceramic Art before 1999

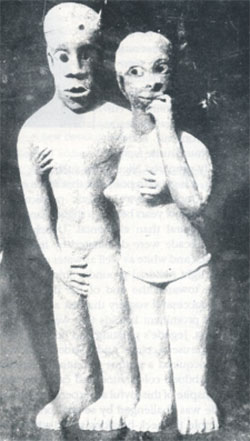

Nigerian traditional art is rich, diverse and has a long history. Some important works in clay have been associated with the Iron Age in Africa and historians have traced a major evidence of the early use of iron in Africa to the West African country of Nigeria.13 In central Nigeria, between the Niger and Benue Rivers, remains of iron-working were found and named Nok Culture after the village in the same area called Nok. The early Iron Age site dated about 300 BC. Of particular interest are series of terracotta sculptures left behind by the Nok people. (Fig.1) These baked clay figures are characterised by barrel shaped volume, perforated eyes and thick-set lips, and were later to inspire a number of modern Nigerian artists beginning in the 1960s. Other important artefacts of clay origin include the Igbo Ukwu earthen pots and the Ife terracotta heads.

|

Fig 1. Terracotta head from Nok, Nigeria, ca. 300BC. |

While the traditional art of Nigeria has a fairly long history, its modern art has a short one and began with the work of the pioneer painter Aina Onabolu in 1903.14 Onabolu (1882-1963) has been described as ‘the first contemporary artist in Nigeria, possibly in Africa south of the Sahara’.15Essentially a portrait artist, Onabolu was the pioneer art teacher in Nigeria who taught in some schools in Lagos. Through his persistent advocacy for art educational programme in Nigeria’s educational system, the British colonial administration hired Kenneth C. Murray from England to teach art in a number of secondary schools in different regions of Nigeria, especially in Lagos, Ibadan and Umuahia. Murray has been credited for infusing local content into his training strategy by encouraging his students to paint genre subjects such as palm wine tapping and village market scenes. His first five notable students, trained between 1933 and 1936, were C. C. Ibeto, Uthman M. Ibrahim, D. L. K. Nnachy, A. P. Umana and Ben Enwonwu. Although none of these pioneer contemporary Nigerian artists developed as a ceramist, there is evidence that Murray taught his students how to construct simple kilns, fire and glaze works in clay. This indicates the earliest attempt to inculcate ceramic art into the Nigerian educational programme. Murray did much more. He was reported to have worked with some local potters to teach them how to modernise their production by using kilns and glazes, although the initiative could not be sustained.16

Although some writers have referenced the existence of a modern pottery studio in Ibadan in 1904, run by an expatriate potter, D. Roberts, with male-only recruits for nine years before his departure,17 there have been no further textual or visual evidence to give further insight into the nature of their products. The first well documented modern pottery in Nigeria is the Abuja Pottery Training Centre established in 1951 by the northern Nigerian government through the instrumentality of the British potter, Michael Cardew, and later Michael O’Brien. The Abuja Pottery Centre encouraged local potters being trained there to blend traditional pottery forms and techniques with foreign ones. It produced the famous Ladi Kwali who took advantage of the high-fired kilns and glazes to modernise her innovative traditional designs, a successful venture that has been appreciably studied by a number of writers, including the Nigerian ceramist and art historian John Agberia.18 This synthesis of local forms and techniques with those from outside for the enactment of modern ceramic works in the early 1950s marked an important precursor to events that took place later that decade at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST), Zaria (now Ahmadu Bello University). There at Zaria in 1958, a group of students, led by Uche Okeke, popularly referred to as ‘Zaria Rebels’, formed the Art Society and rejected the academic programme that had little or no African content.19 They issued a manifesto called ‘Natural Synthesis’ by which they sought to borrow the best from their Nigerian traditional past and blend them with the best from outside for the sake of a distinct identity. According to Simon Ottenberg:

this involved the acceptance of much of European media and technique (although not barring experimentation with these) and the development of styles and content close to the students’ Nigerian experience, whether it be their own cultural tradition, that of other Nigerian cultures, or current Nigerian life.20

After their graduation from Zaria in 1960 and 1961, one of the members of the Art Society, Demas Nwoko, began to explore terracotta sculptures in the Nok style in a creative project that has been described by the Nigerian art historian Chike Aniakor as a ‘revival of Nok terracotta’.21 He organised workshops in Ibadan in 1966 to teach a modified system of the traditional open-firing techniques and to inspire more interest in the clay medium.22 According to Aniakor:

Fascinated by the rich textures of terra-cotta works such as those of Nok and even traditional pottery and impelled by a desire to achieve similar results in his works, Nwoko sought after a new firing device. The traditional mode of firing does not generate enough heat which is limiting in terms of the artist’s needs. The modern method of kiln firing is also limited because it imposes a uniform colour to a pottery piece. As a compromise solution, the artist devised a firing method ‘in which the fuel used, in this case teak, would burn in direct contact with the objects in the kiln’. The fusion of tradition and change, of creativity and innovation are implied in this technical solution.23

Nwoko became the first contemporary Nigerian artist to produce very expressive works in baked clay. (Fig.2) He drew inspiration not only from Nok terracotta heads but also from other sources, including Yoruba wood sculptures in which the head is usually one-third of the entire body size.

|

Fig 2. Adam and Eve by Demas Nwoko. |

From the early 1970s, a significant development, championed by the American-trained Igbo ceramic artist, Benjo Igwilo, took place at Nsukka. In 1973, Igwilo had joined the teaching staff of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, with an MFA in ceramics from Alfred University, New York, USA. He began to extend the work of Michael Cardew and Ladi Kwali of the Abuja Pottery fame by blending engobe decorations and glazes with the pottery forms and techniques of the Igbos of south-eastern Nigeria. Interestingly, he did this using the formal and aesthetic resources of the Igbo traditional body and wall painting practice (called uli), a peculiar creative exploration that characterized the Nsukka School for over three decades. Igwilo and his students of the 1970s (especially) and of the 1980s became well known for high-fired ceremonial and ornamental pots that forged a synthesis of the traditional and the modern. (I benefitted from Igwilo’s pedagogy during my undergraduate studies at Nsukka, and was privileged to work very closely with him in his private studio, in the 1990s).

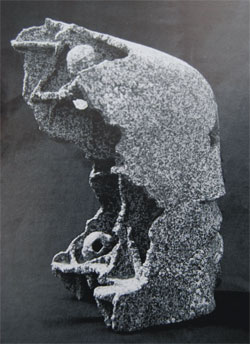

Later in the late 1970s, El Anatsui (currently regarded highly as the leading contemporary African artist) explored stoneware clay (manganese body) for his ‘Broken Pots’ series before his more well known mural wood sculptures and aluminium foil tapestries. His sources included Nok terracotta (Fig.3) and Igbo Ukwu earthen pots (Fig.4). El Anatsui is a Ghanain-born experimental sculptor who taught in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, since 1975. One of Anatsui’s students Chris Echeta (who majored in ceramics at Nsukka) has worked in the clay medium, producing political works, from 1979 till date. Echeta’s choice of materials has revolved around clay, engobe and glaze.

|

Fig 3.Chambers of Memory by El Anatsui. |

Fig 4. We de Patch am by El Anatsui. |

Also from the 1970s, Ige Ibigbami explored staked terracotta pots at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Ife, Ile-Ife, south-western Nigeria. He drew inspiration from traditional Yoruba pottery for the creation of works that have been described as ‘pillar pots’. The works are so labelled because of their installation format which takes the form of a series of pots set one on top of the other until they tower into a pillar form. ‘Pillar pots’ became a style in ceramic art associated with the Ife artists, such as Tunde Nasiru, and was carried on there until recently.

In the 1980s, Abbas Ahuwan of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria (who in the 1960s was trained at the Abuja Pottery Centre), championed experiments in burnished and smoked pot sculptures that made references to northern Nigerian architecture, musical instruments and traditional Hunkuyi decorative forms.24 Also beginning in the late 1980s, Ruben Igbine of the Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi, produced series of stoneware figurative sculptures that addressed genre themes and subjects.

The above narrative represents the major streams of ceramic art development in Nigeria up to the end of the 1990s. It shows that there had been no radical departure from the use of clay and glaze for utilitarian, decorative or political expressions. My emergence in the scene, especially after my MFA studies in ceramics in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka (1998-2001), brought a departure to the hitherto closed boundaries of clay working in Nigeria. My artistic agenda was to explore the possibilities for installations using ceramic elements along with other media such as wood, paper and metal.

By February 2003, works in my mixed media project titled ‘Casualties’ was shown in Lagos at a solo exhibition organised and sponsored by the French cultural centre. One of the works in the series that drew greater attention was Suyascape IV. Perhaps it did so not only because of its formal strategies but also for its political message, for the USA was at the time of the exhibition preparing to go to an avoidable war in Iraq. Since 2003, works in the ‘Suyascape’ series have been shown at a number of slide presentations in the USA. Suyascape IV was one of ten works that gave me a place at the 2008 summer residency of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, USA. This paper therefore aims to provide a closer insight into the ‘Suyascape’ series, which is an important representative work in my transgression of the conventional ceramic sculptures in the Nigerian context.

The Suyascape Series

‘Suya’ is a country-wide name in Nigeria, and in the West African sub-region as well, for a popular delicacy produced by grilling slices of fresh meat. Their most fashionable forms are those created by driving carefully prepared sticks through multiple slices of the fresh meat before they are grilled in make-shift or permanent barbecues. These are usually garnished with spices, most especially ground pepper and sliced onions.

In terms of their formal features, a collection or arrangement of ‘suya’ at a barbecue exudes very striking aesthetic patterns. In most cases the ‘suya artists’ exhibit such an exciting technical virtuosity in the handling of their own kind of ‘mixed media’ work (comprising animal flesh, sticks, pepper and onions) such that they arrive at compositions or installations that are visually compelling and which communicate directly with viewers and attract their patronage.

I was drawn to the ‘suya’ makers as ‘mixed media artists’ who employ natural resources and processes to concretise their art ideas. I was impressed not only by the visual impact of the ‘Suyascape’ but was also inspired by its conceptual possibilities. The typical Nigerian ‘suya artist’ has therefore fired my imagination to explore earthenware clay, metal rods and blocks of wood for a number of installations. (See Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8)

|

Fig 5.Suyascape I, 2001, terracotta, metal and wood. |

Fig 6. Suyascape II, 2001, terracotta, metal and wood. |

|

Fig 7.Suyascape III, 2003, terracotta, metal, wood and acrylics. |

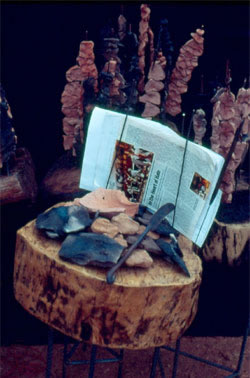

Fig 8. Suyascape IV, 2003, terracotta, metal and wood, 143x127x89cm. |

Materials

As already hinted above, basic materials used are earthenware clay (mixed with laterite earth), metal rods and blocks of wood. My choice of earthenware clay is based on its visual vocabulary that tends to reflect both the coffee brown colour and the tactile qualities of ‘suya’. Metal rods were used for their ability to withstand kiln temperatures to a workable extent. Wooden blocks were useful for simulating barbecues upon which the sticks of terracotta ‘suya’ were installed for unique visual impact. Selected back issues of local and international magazines (relating to events of war and violence) were also appropriated for the sake of extending their iconographic contents.

Technical Procedure

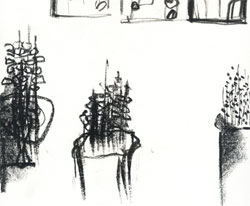

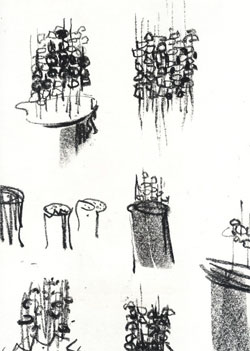

Thumbnail sketches were used for exploring basic ideas and installation possibilities (Figs. 9, 10 and 11). Earthenware clays were either formed into little slabs before leather hard stage or were cut directly, with the aid a sharp pen-knife, into slices from a lump of relatively hard clay. The thickness of the slices of clay was such that the metal rods could pass through them from edge to edge. The metal rods used were cut into lengths of between 45cm and 200cm.

|

Fig 9. Working drawings I. |

Fig 10. Working drawings II. |

|

Fig 11. Working drawings III. |

The rods, driven through the clay slabs, were allowed to dry together (after ground laterite stone were sprinkled on them to simulate local spices) and then carefully fired to about 700-8000C. At this temperature range, the metal rods were found to have remained somewhat stable.

Blocks of wood were prepared and multiple holes drilled into them (from the top) using power tools. The drilling bids were such that could produce holes capable of tightly holding the sticks of ‘suya’. The blocks of wood were burned in open fire to darken them and simulate the antique nature of barbecues. They were then sandpapered and fixed with wood lacquer.

A select number of the bisque-fired sticks of ‘suya’ were carbonised in bonfires, resulting in visual contrasts in the colour of the entire collection.fThe sticks of ‘suya’ were than installed into the holes in the wooden blocks. As in Suyascape IV (Figs. 12 and 13) the installations were finally further activated using extracts from magazines in ways that do not only add extra colour to the entire collection but also extend the frontiers of the conceptual ideas.

Conceptual Notes

Beyond the aesthetics of the formal qualities of a ‘suyascape’, it holds a strong metaphor for human dignity. When people gather at barbecues to buy and eat grilled meat, it is a metaphorical gathering for the celebration of human dignity – a silent recognition that animals should rather be killed, hacked, sliced and roasted in fire and not human beings. This is a direct reaction to the fact that we have witnessed gory sights in many parts of Africa, the Middle East and other parts of the world when people committed genocide or pogrom against others or engaged in wars and violent conflicts. Cuttings from old magazines have contributed texts and images (on the subject of war and human cruelty) to the installation in Suyascape IV (Figs. 12 and 13). The idea has been drawn directly fromlocal practices common with the ‘suya’ sellers who often use pages of old newspapers and magazines to package or wrap the delicacies for their customers. Often times, at close examination of these packages or wrappers, one finds stories, pictures or editorials on past events that are relevant to current issues or events. By my use of back issues of an international magazine such as the New York Times (in which ‘India’s killing frenzy between Muslims and Hindus’ was both reported and illustrated (as in Figs. 14 and 15), I have sought to draw attention to man’s failure to learn from past history, leading to a mindless repetition of very horrific history in different parts of the world.

|

Fig 12. Suyascape IV (detail I), 2003, terracotta, metal, wood and text 143x127x89cm. |

Fig 13. Suyascape IV (detail II), 2003, terracotta, metal, wood,and text 143x127x89cm |

|

Fig 14. Sample Magazine Text I. |

Fig 15. Sample Magazine Text II. |

‘Suyascape’ raises questions relating to man’s inhumanity to man. It seeks to question today’s bombing, maiming and butchering of men by fellow men in different parts of the world, as well as their roasting in fire, as have been demonstrated, for example, during terrorist attacks. ‘Suyascape’ also makes subtle references to accident scenes along the bad roads in many African countries. Most roads in Africa are currently punctuated by the charred remains of crashed vehicles that must have sliced human flesh into bits of ‘suya’ and also roasted them in fire.

Conclusion

‘Suyascape’ has demonstrated the visually and conceptually powerful role which clay can play as a medium in mixed-media sculptures and installations. Its roles in the expansion of art ideas are evident in my ‘suyascape’ project. One can therefore safely assert that clay remains a primal medium charged with great potentials for heavy artistic statements and cannot be ignored simply because it has for so long been associated with what modern-art-oriented historians and critics call ‘craft pottery’. Interestingly, following the examples of my work, this realisation has recently fascinated and inspired new directions by a number of other emerging contemporary Nigerian artists such as Cauis Onu, Ngozi Omeje and Alozie Onyirioha. It is likely that many more emerging artists interested in clay work will explore this mixed media approach for the installation art form that is currently taking root in Nigeria.Notes

- For details, see Tonie Okpe, ‘Interrogating the Human Figure in Bridging the Ceramic-Sculpture Divide: Practice in Nigeria’, Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 8, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue008/articles/18.htm. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Ozioma Onuzulike, ‘Ceramics without Borders’, Ceramics Technical , No.18,2004, pp. 72-74. back to text

- See Ozioma Onuzulike, ‘My Hands in Clay and Other Media: The 'CASUALTIES' Project , Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 7, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue007/articles/04.htm back to text

- Onuzulike, ‘Ceramics without Borders’ back to text

- Moses M. Fowowe, ‘Socio-Cultural and Religious Uses of Traditional Pottery Among the Yoruba, Bini and Igbo People of Southern Nigeria’, USO: NigerianJournal of Art, vol.3, nos.1&2, 2001, pp. 9-12. back to text

- Moira Vincentelli, ‘Gender and Ceramics: Old Forms and New Markets’, Interpreting Ceramics, Issue10, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue010/articles/introduction.htm back to text

- T. Shaw, Igbo-Ukwu: An Account of Archaeological Discoveries in Eastern Nigeria, 2 Vols. Evanston, Ill, Northwestern University Press, 1970. back to text

- Sylvia Leith-Ross, Nigerian Pottery, Ibadan, University Press, 1970. back to text

- My MFA project report is titled ‘Transgressing the Boundaries: Ceramic Elements in Mixed Media Sculpture’, Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 2001. back to text

- Onuzulike, ‘Ceramics without Borders’. back to text

- Basil Davidson, A History of West Africa 1000-1800, Longman Group Limited, London, 1965, p.13. back to text

- Considerable work has been done on the life and work of Onabolu, especially by the Nigerian art historian, Ola Oloidi. See, for example, Ola Oloidi, ‘Onabolu, Pioneer of Modern Art in Nigeria: An Introduction’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, pp.1-9. back to text

- Simon Ottenberg, New Traditions from Nigeria: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group. Seattle and Washington, D.C., University of Washington Press and National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1997, p.17. back to text

- Moses Oladipo Fowewe, ‘Changing Phases of Tradition: The Origin and Growth of Contemporary Pottery in Nigeria’, CPAN Journal of Ceramics, no.1, November 2004, p.12. back to text

- See Fowewe, ‘Changing Phases’; A. M. Ahuwan, ‘Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria: 1952-2002: Achievements and Pitfalls’, Ashakwu: Journal of Ceramics. vol.1, no.1, June 2003, pp.18-22; A.M. Ahuwan, ‘Trends in Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria’, ENVIRON: Journal of Environmental Studies, vol.1, nos.2&3, 1999, pp.32-39; John-Tokpabere Agberia, ‘The Ceramics Industry in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, pp.64-72 back to text

- John T. Agberia, Ladi Kwali: A Study of Indigenous and Modern Techniques of Abuja Pottery, Ibadan, Kraft Books Ltd, 2007. See also Stephen A. Telkins, ‘Abuja: Continuing a Nigerian Tradition’, Interlinks: The Nigeria American Quarterly Magazine, vol.7, no.1, January – March 1971, pp. 3-6. back to text

- See Ottenberg, New Traditions from Nigeria, p.32. back to text

- Ibid. back to text

- Chike C. Aniakor, ‘The Contemporary Nigerian Artist and Tradition’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, p.16 back to text

- For a detailed account of the Demas Nwoko workshops, see Dennis Williams, ‘A Revival of Terra-cotta at Ibadan’, Nigeria Magazine, no.88, 1966, pp.4-13. back to text

- Aniakor, ‘The Contemporary Nigerian Art’, p.16. back to text

-

T. Okpe, ‘The Seemingly Sculptural (Un)Intention of a Potter: The Paradox of Abbas Ahuwan’s Forms’, Ashakwu: Journal of Ceramics, Vol.1 No.1, June 2003, p.42. back to text

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

References

Agberia, J. ‘The Ceramics Industry in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, pp.64-72.

Agberia, J.T., Ladi Kwali: A Study of Indigenous and Modern Techniques of Abuja Pottery, Ibadan, Kraft Books Ltd, 2007.

Ahuwan, A.M., ‘Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria: 1952-2002: Achievements and Pitfalls’, Ashakwu: Journal of Ceramics. vol.1, no.1, June 2003, pp.18-22.Ahuwan, A.M., ‘Trends in Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria’, ENVIRON: Journal of Environmental Studies, vol.1, nos.2&3, 1999, pp.32-39.

Aniakor, C.C., ‘The Contemporary Nigerian Artist and Tradition’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, pp.10-19.

Davidson, B., A History of West Africa 1000-1800, Longman Group Limited, London, 1965.

Fowewe, M.O., ‘Changing Phases of Tradition: The Origin and Growth of Contemporary Pottery in Nigeria’, CPAN Journal of Ceramics, no.1, November 2004, pp. 4-13.

Fowowe, M.M., ‘Socio-Cultural and Religious Uses of Traditional Pottery Among the Yoruba, Bini and Igbo People of Southern Nigeria’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol.3, nos.1&2, 2001, pp. 9-12.

Leith-Ross, S., Nigerian Pottery, Ibadan, University Press, 1970.

Okpe, T., ‘Interrogating the Human Figure in Bridging the Ceramic-Sculpture Divide: Practice in Nigeria’, Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 8, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue008/articles/18.htm

Okpe, T., ‘The Seemingly Sculptural (Un)Intention of a Potter: The Paradox of Abbas Ahuwan’s Forms’, Ashakwu: Journal of Ceramics, Vol.1 No.1, June 2003, pp. 40-44.

Oloidi, O., ‘Onabolu, Pioneer of Modern Art in Nigeria: An Introduction’, USO: Nigerian Journal of Art, vol. 2, nos. 1&2, January 1997 – December 1998, pp.1-9.

Onuzulike, O., ‘Ceramics without Borders’, Ceramics Technical, No.18, 2004, pp. 72-74.

Onuzulike, O., ‘My Hands in Clay and Other Media: The 'CASUALTIES' Project, Interpreting Ceramics, Issue 7, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue007/articles/04.htm

Onuzulike, O., ‘Transgressing the Boundaries: Ceramic Elements in Mixed Media Sculpture’, Unpublished MFA Thesis, Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 2001

Ottenberg, S., New Traditions from Nigeria: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group. Seattle and Washington, D.C., University of Washington Press and National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1997

Shaw, T., Igbo-Ukwu: An Account of Archaeological Discoveries in Eastern Nigeria, 2 Vols. Evanston, Ill, Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Telkins, S.A., ‘Abuja: Continuing a Nigerian Tradition’, Interlinks: The Nigeria American Quarterly Magazine, vol.7, no.1, January – March 1971, pp. 3-6.

Vincentelli, M., ‘Gender and Ceramics: Old Forms and New Markets’, Interpreting

Ceramics, Issue 10, http://www.uwic.ac.uk/ICRC/issue010/articles/introduction.htmWilliams, D., ‘A Revival of Terra-cotta at Ibadan’, Nigeria Magazine, no.88, 1966, pp.4-13.

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated

Pushing the Boundaries of Ceramic Art Tradition in Nigeria • Issue 11