Interpreting Ceramics | issue 17 | 2016 Articles, Reviews |

|

||||||||||||||

Extermination Tents: The maker’s perspective on displaying new ceramicsby Kim Bagley an artist from Durban, South Africa. She recently completed a practice-led PhD in ceramics at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham and is a studio resident at 318 Ceramics, Farnham Pottery. She writes here as an artist. |

|

||||||||||||||

|

The installation discussed in this article formed part of a practice-led PhD at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, awarded by the University of Brighton in January 2015. A section of Chapter 4 of the written thesis that accompanied the viva exhibition explores this work in detail and so covers some of the material in this article. This article is not a re-worked version of the thesis but there are references and ideas that appear in both. Abstract

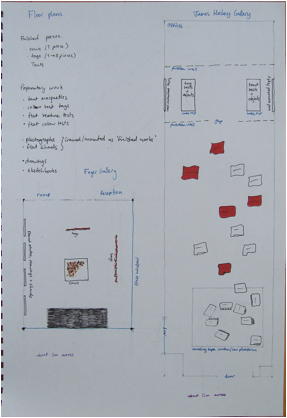

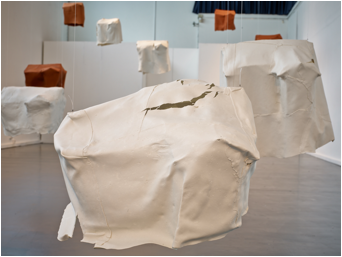

This article is an artist’s perspective on the public display of African ceramics. It is written in the first person, and reveals how I conceived of a ceramics installation, Extermination Tents, from conception, through to design and installation in the gallery context. This approach to displaying ceramics also has the potential to translate into a museum context. Aspects of museum displays of African ceramics have, in turn, influenced my own installations. Extermination Tents was first shown in its entirety at the James Hockey Gallery, University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, 24th June – 18th July 2014. The Extermination Tents installation consists of a group of pieces that sit on the ground, as well as work designed for suspending from above. The final installation consisted of 10 suspended tents and 9 placed on the gallery floor (Fig.1). It formed a major part of the output of my practice-led PhD thesis, which explored notions of ‘African-ness’ in contemporary ceramics using a skin-clay metaphor.

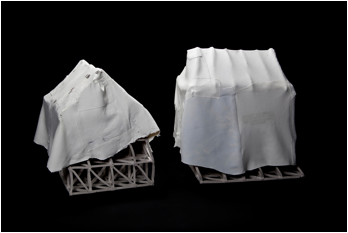

In Durban, particularly in older, historically white suburbs, there is a problem with Wood Borer and white ants (termites). They thrive in the hot and humid Durban weather. These wood eating insects damage furniture, wooden roof-trusses and any other untreated wood they can find. Some of these insects are indigenous but others, such as the Bamboo Borer (Dinoderus minutus), arrived from other parts of the world on ships, reminding us that Durban is an international trade port where both goods and people from all over the world arrive, pass through or leave. If a house is infected with Wood Borer, the usual way to eradicate them is to cover the house, rather conspicuously, in a large tarpaulin tent and then release poison inside (Fig.2).

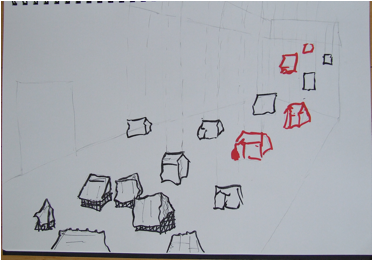

Translating tents into clay: Tents and traces It was not only the tent forms that interested me. There are other, more subtle visible, visual signs of the insects that I used in my ceramics. If your house is infected you are unlikely to see the insects themselves unless you know what you are looking for. Even then, you are more likely to see traces of their invasion than the creatures themselves. This includes small holes in furniture or books and dust on shelves, pelmets and dado rails. The ambiguity of this invisible threat to suburban life (with a very visible means of removing that threat) appealed to me. I used the aesthetics of the traces to decorate the surfaces of some of my tent forms, in a subtle homage to these small traces. Some have little pockmarks and dark dust-like marks. Some of these are purposeful marks I made with metal oxides applied to the surface and others are happy accidents from the firing process. The old gas kilns used to fire the white porcelain tents tend to leave little specks of minerals from previous firings or from the slowly degenerating walls of the kilns. Using visual evidence of borer infestations, fumigation tents and Wood Borer traces as my starting point, I began making a series of tents. After a few early experiments with making tent forms, the initial idea was to create an ethereal floating tent-city. Even at this early stage, the idea of hanging the objects from the ceiling was in my mind, as demonstrated by the very early sketch shown in Figure 3.

While ceramics has historically enjoyed an expanded physical relationship with landscape and architecture, and thus the expanded field, it was not until after ‘installation’ art became popular in international sculpture and painting, that it took hold in the realm of artistic ceramics in more recent times. On the (re)emergence of ‘installation’ in late twentieth century ceramics Edmund de Waal wrote:

Ceramics, when displayed in galleries in the twentieth century, seemed not to participate in equivalent developments in sculpture, explained by Rosalind Krauss in 1979 as ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’.2 There have been many artists working with ceramics who work in a way more closely aligned with modern and contemporary sculpture (and beyond it) who exist in this ‘expanded field’. These artists have influenced the way I approached the design for Extermination Tents and I see my work as a continuation of this tradition. On the international art scene, the participatory installations of British ceramist Clare Twomey and sculptor Antony Gormley’s memorable Fields of ceramic figures are the type of works that have influenced my own practice. Artists like Twomey and Gormley have ‘broken the mould’ within the studio ceramics field through their approach to installing ceramic works in the gallery and museum. These artists and the sympathetic curators they work with have expanded the way artists working in clay today (including myself) dare to show their work. The spatial and experiential elements of work by Twomey, Gormley and their peers, continues to influence how I think about exhibition design. In South Africa, comparable examples include the work of Wilma Cruise and Hennie Meyer. Twomey’s work in particular has a participatory element giving the viewer a real, physical sense of the ceramic object. In Consciousness/Conscience (2001-2004) the audience was expected to walk over Twomey’s tiles, breaking them to get to another part of the exhibition. At the V&A Trophy (2006), blue jasper birds, scattered amongst busts and figures, could be taken away by the museum visitor. The small, smooth objects easily held in the hand, could be quietly slipped into a pocket. Inside a ceramics gallery or museum this is still a very unusual and very direct way to get a sense of the physicality of the ceramic material. At the V&A for example, most objects are hidden behind glass; there are only a few select pieces designated for touching and handling. My work exists between these two modes. While I do not go as far as encouraging the theft or destruction of my pieces, the idea of really getting a physical sense of the material and the scale of my work in relation to the human body is an important and distinctive element of my visual language. Extermination Tents was designed to allow the viewer to walk among the ceramics and right up to their surfaces with no cabinet, cordon or plinth to inhibit access. Displaying ceramics in this way is risky, but can be very satisfying for the viewer because the view is not mediated through a conspicuous frame. In the museum context this experience is not safe or practical for most displays. However, there are some precedents in African ceramics museum displays that came to mind. Although my Extermination Tents installation is intended for the white-cube-type art gallery context more than the museum, there are subtle connections to be made between existing museum displays of ceramics and how I approach my work. Museums and their objects are important points of research and inspiration for my ceramic practice.

In the same gallery as the tree-like form, there are glass cases containing a mix of ceramics from different parts of Africa and made in many different times and contexts. The curators have also used proximity to help the viewer see connections between objects. An example of this associative positioning can be seen when one observes an untitled contemporary vessel by Magdalene Odundo, made in 2000, Farnham, England. It is a coil-built and beautifully burnished pot with a very anthropomorphic form. This piece is close to a trio of equally exquisitely burnished Baganda pots of royal origin. Odundo’s pot also shares a glass shelf with a detailed figurative shrine vessel with three main figures, dated late nineteeth century, from Igbo, Nigeria. The figures on the Nigerian piece and Odundo’s figure-like pot both reference inverted cone-shaped headdress forms. Physically close groupings like these encourage the viewer to make connections across times and places based on visual affinities. Their proximity is part of the way meaning is created in this display. In my own practice I use the power of proximity. The careful positioning and distance between objects can give the viewer a sense that the pieces are ‘talking’ to each other. The anthropomorphic relationship between ceramic objects is one of the ways I construct meanings in my work. This is particularly apparent in the front group of tents in the James Hockey Gallery installation, where nine pieces in Extermination Tents sit on the ground (Fig.7).

Installations comprised of many objects have a different impact to that of objects shown singly. Like the British Museum objects bring together related practices across time and place, inferring connections rather than differences; I tend to show my work as crowds or groups showing the similarities and differences between the pieces which are all both alike yet very individual. This is my way of meditating on human relationships and communities.

Before attempting this major installation, I used 5 of the earlier hanging pieces to create an installation in the Foyer Gallery, at UCA Farnham as part of a group exhibition in 2013 (Fig.8). This made me aware of how the objects worked together in space, and what the experience would be like for the viewer. I used this exhibition to test mundane but important aspects including how much they moved, how close together they should be hung and it gave me an idea of how close viewers tended to get. Like many of the vessels on the tree at the British Museum, these pieces could not be displayed on a flat surface. I prefer this because it removes the distraction or association of gallery furniture or tableware conventions, focussing the viewer on the sculptural and material qualities of objects themselves. In positioning them for hanging I wanted to use both geometric and organic lines to echo this contrast. A simple solution was to hang them at different points on a grid, but at different heights. I think this adds to the sense of lightness as well as my concerns about contrast and ambiguity, both of which are important formal and conceptual elements of this work. Viewers could get right up close to see the details of tears, folds and kinks in the clay surfaces. I avoided crowding the space with too many pieces. They moved very slightly because they were suspended. The combination of their fragile appearance and the slight movement meant that viewers tended to approach them slowly and cautiously even though they were installed in a busy reception area.

As Odundo has in these coiled pieces, in Extermination Tents I tried to achieve a sense of movement. The twisting and leaning of inner support structures gives the tents their movement. Weaknesses built into the design deliberately cause the stoneware to twist or lean under the weight of the porcelain (Fig.10).

Moving back from the front group I planned to suspend the remaining tents, arranged according to a loose grid pattern, suggesting some of the order of urban planning, yet appearing to float up and away in an organic manner, loosely from front to back. The pieces, made from thin porcelain and terracotta paper-clay are light and organic. Some form a casual group in the front of the exhibition, as you move towards the back of the space the format becomes more geometric, but at the same time variation in height counteracts this formality. Despite the geometric house-like structure the forms themselves appear quite soft, like textile or paper, and yet are hard fired ceramic (Fig.13). This contrast and ambiguity between softness and hardness, sharp edges and rounder ones, grids and curves are elements that describe to me the ambiguous relationship many South Africans have with their country.

Notes 1 Edmund De Waal, 20th Century Ceramics, London, Thames and Hudson, 2003, pp184. 2 Rosalind Krauss, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, October, Vol. 8, Spring, 1979, pp. 30-44. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

|||||||||||||||

Extermination Tents: The maker’s perspective on displaying new ceramics • Issue 17 |