|

CLAY: Keramickmuseum, Danmark, (Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark) re-opened after extensive renovations in May 2015. They opened with Brandes and Bindesbøll, an exhibition featuring the works of two giants of Modernist Danish ceramics Peter Brandes and Thorvald Bindesbøll. Almost one hundred years separate the two artists. Peter Brandes was born in 1944. Thorvald Bindesbøll was born in 1846. The pairing is fascinating because as similar as the two artists are stylistically, their work is substantively distinct to the point of being contradictory.

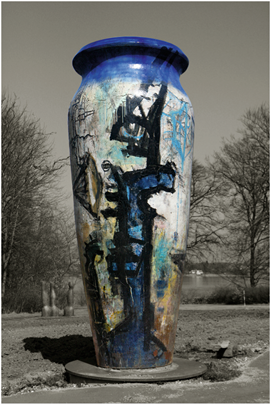

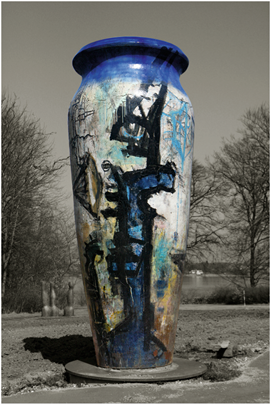

The two artists share a style. They both create visceral indulgences of the massiveness of clay. Almost every element of their work celebrates the heavy, base physicality of clay. Their forms are oversized with a massively heavy appearance. They both mute their geometry. Their forms bend gradually eschewing sharp changes. Visually this creates an effect where it feels as though their shapes are defined to some extent by their weight. However, Brandes’s forms are slightly more elongated than Bindesbøll’s. Both artists use relatively squatty proportions.

Fig 1. Peter Brandes Sevilla Krukke |

Finally, each artist decorates his work with a kind of automatic drawing style. Their work resonates with a certain 'too testosterone poisoned to draw a straight line,' aesthetic. Their marks are violent, energetic and immediate. The apparent likeness contradicts a fundamental difference in how Brandes and Bindesbøll engage their world. Understanding this fundamental difference helps to unlock one of the most important texts of the twentieth century.

Fig 2. Thorvald Bindesbøll |

Foucault’s book Archaeology of Knowledge offers an examination of discourse—Foucault’s term for the construction of thought. It proposes an alternate methodology he refers to as Archaeology. Foucault’s argument is that discourse creates an illusion of objectivity. There are many methods it achieves to this end, one of which is highly relevant to Bindesbøll’s work. Foucault states that discourse operates on a continuum that spans totality and plethora. This is the difference between shared characteristics that place an object within a totality and, as he stated in Archaeology of Knowledge: 'establish a law of rarity.' Talking about this interaction he goes on to explain:

We must look therefore for the principle of rarefication or at least of non-filling of the field of possible formulations as it is opened up by the language (langue). Discursive formation appears both as a principle in the entangled mass of discourses and as a principle of vacuity in the field of language (langue).

While he is talking about language—the same dynamic can and does apply to the image or the text. Like language, a picture refers to something else. Culturally, both words and objects can be defined by two things: totalities and rarities. Totalities are like a pyramid. They begin with broad categories, reducing all the way to very narrow categories. My dog is organic. My dog is an animal. My dog is a dog. My dog is a Labrador retriever. At the top of pyramid are qualities unique to that entity. It is here that rarity is established.

This distinction resonates in Bindesbøll’s work. His signature style of quick slashes that congeal into minimally cohesive holes deals directly with the rarity of the object he is depicting. It is like a visual shorthand where Bindesbøll’s only concern is capturing that signature characteristic that is exclusive to its subject—like the particular color or petal configuration of a specific flower. Looking at his paintings on his untitled earthenware, all he gives are those details he views as important to identifying the subject. This dynamic serves to reinforce the totality and plethora polemic Foucault describes. Ironically, by stripping his subjects of all of their shared qualities, Bindesbøll asserts the authority of these shared qualities.

Concern with rarity transcends the artist’s works and affects his entire life. In the exhibition catalog: Brandes and Bindesbøll: Binding and Breaking, Henrik Wivel observes:

By gradually eschewing the illustrative elements in his ceramics, Thorvald Bindesbøll was able to retain certain perennial features from the history of ornamentation in his work, by means of contrast improvisations and formal experiments, moving it into the modern arena.

This statement seemingly casts Bindesbøll as fractured. Fracture is perhaps one of Foucault’s most difficult concepts to believe. It is a radical construction of history that rejects both chronology and effect. To understand the difference traditional history is like dominos, all clicking along, cause becomes effect becomes cause. Foucault’s archaeology history is much more like popcorn: the pop into history. While there is a cause, unlike dominos, it is not a cause that can be charted.

Bindesbøll work is not a fracture because it subverts its own conventions and disciplines. It breaks down the rules of decorative ceramics but stays within its space. In detailing the methodology of archaeology, Foucault states that discursive formulations “are very different from epistemological or ‘architectonic’ descriptions, which analyse the internal structure of a theory; archaeological study is always in the plural.” No matter how subversive Bindesbøll’s work is, it only subverts its own formations.

Fig 3. Exhibition view |

The question is, does Brandes work a true interruption? Brandes’s work does fracture away from Bindesbøll, or at least how he describes him. As much as one way pulls away from tradition, the other moves toward traditional craft.

In an interview about the connection between his work and Bindesbøll’s, Peter Brandes observed, 'In contrast with Bindesbøll, who works on the surface and only scratches into it, I work with a three-dimensional surface treatment of the clay.' This observation is immediately evident in Brandes’s work. He chops into, and adds onto his clay. He also works his surfaces in layers. Brandes builds his images in layers of slashes and brushes of paint. He constructs these images in a much more painterly way. His images seem derived far more from artists like Edvard Munch, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Francis Bacon. Merging expressionistic painting with pottery can be a discursive act.

Most of Brandes’s subjects, figurative works referring to mythical and biblical themes, are highly traditional. Additionally, the forms he works on are far more traditional than those of Bindesbøll. His vases have lips, necks and shoulders. Although amazingly prolific, Brandes only uses a small number of forms. While he does work on many different subjects; i.e. the virgin, a man sowing seeds and John the Baptist, he will work and rework these subjects many times. While radically distinct in style and scale, Brandes’s forms and subjects are essential to decorative ceramics.

There is a deep irony between the work of Brandes and Bindesbøll, and Michel Foucault. Arguably, the difference in how they construct their images would be completely transparent without Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge. Suggesting that the distinction was less observed than prescribed. On the other hand, once applied to the two artist’s works—it makes Foucault’s ethereal argument rather corporeal. Is the thesis a valid sophism or an enlightening fiction? Either way, it is unarguably Foucauldian.

Images provided by the Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark

Mr. Merino is a US based artist, critic and curator. An exhibition he curated Domestic Mysteries, will be opening at the New Taipei City Yingge Museum of Ceramic Arts in 2018. He has several papers and talks listed on his webpage: https://independent.academia.edu/TonyMerino

Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

|