Interpreting Ceramics | issue 15 | 2013 Conference Papers & Article |

|

||||||||

Subversive Ceramics: On Satire and SubversionClaudia Clare |

|

||||||||

|

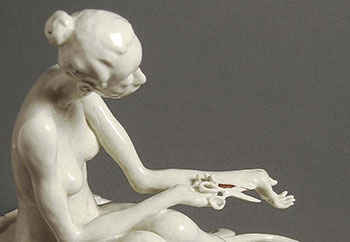

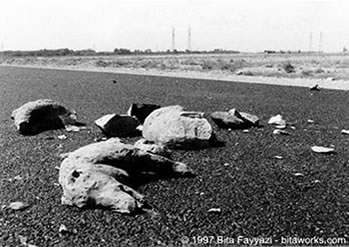

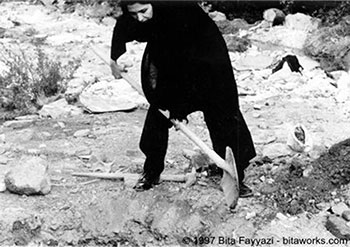

This text was originally presented as a paper at the Subversive Ceramics: Exploring Ideas in Contemporary Ceramic Practice symposium at the Holburne Museum, Bath, 9 November 2012. Key words: Bita Fayyazi, Justin Novak, satire, grotesque, allegory, subversion, irony, burlesque, theocracy, feminism, figurine. Introduction When writing The Pot Book in 2011, I was struck by the sheer volume of current ceramic work which deployed the tried and tested method of using a familiar or traditional ceramic form and modifying it, slightly, to change its meaning and generate a new narrative.1 As often as not, the new narrative would be a social or socio-political comment. This process was almost invariably referred to as a ‘subversion.’ The Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘subvert’ or ‘subversive’ insists on its political character and intention. To subvert is a strong word, or should be. It means ‘to overthrow’ or ‘overturn,’ usually with reference to a regime or government. A ‘subversive’ is defined as a revolutionary. To subvert something means to do a good deal more than just give it a tickle. The term ‘subversion,’ in the context of ceramics, appears to be far broader, however, encompassing modifications in design to make an object look more contemporary as well as those that allow the artist to develop a political narrative or critique. If the ‘subversion’ in a ceramic work is intended to be entertaining to some degree, satire, which is very good at upending meanings, will often deliver. Modifying the form to tweak its accepted meaning might produce a satire which is specifically ceramic. If, however, the artist is concerned with serious political subversion – something which constitutes and can be understood as a threat or challenge to a ruling social or political order or that confronts a dominant social order – both the artist and the art work must shift into a different sphere. This kind of work becomes part of the territory where art meets political activism and therefore requires a sophisticated knowledge and understanding of the political context. Satire, in this situation, may prove self-defeating, since the mechanics – the tropes – of satire can undermine the very political narrative they seek to produce. Defining Satire On the definition of satire, there is little disagreement. It aims to attack or, at the very least, expose and ridicule the ‘vice and folly’ of others, in particular those others in position of power or authority. 2 Caricature, cartoon, the grotesque, obscenity, invective, morbid sarcasm, irony, pathos, pastiche, parody and, in certain situations, allegory, are all devices in the armoury of satire.3 As Linda Hutcheon, in her study of irony, observes, whether or not the satire hits the target, whether or not the audience ‘gets’ the satiric comment, is somewhat dependent on the audience being a member of the correct ‘discursive community.’4 Ceramic satire is an excellent example of this since, almost invariably, it depends on the audience being ceramic or craft aficionados. A slight modification, then, is required to establish what satire might be in a cotemporary context. It attacks social norms but they are the norms of ‘others,’ whoever that social ‘other’ may be and they may not always be socially powerful. A good example of this would be the ceramic work of Grayson Perry whose main target is the social and sexual mores of the lower middle class, a demographic which is not marked by its social or political power or influence and is, relatively speaking, an easy target. It was powerful for him, personally, however, when he was growing up. His other target is the art world and the art market, which would be much more recognisable as a site of considerable power and cultural influence. The purpose of satire and its relationship to subversion In principle, if satire really did attack the seat or source of power, it would, by definition, be subversive but it does not always succeed and, in any case, that may not be its purpose. There is some dispute among scholars as to the purpose of satire. Gilbert Highet asserts that satire has a moral principle, that it aims ‘to stigmatise crime or ridicule folly and thus to aid in diminishing or removing it.’5 Dustin Griffin, however, rejects this higher moral principle. He refers to satire as the ‘lawless and wild,’6 in particular he takes issue with theorists who propose an organised, directive reformist presence in satire. ‘Satire,’ he writes, ‘is problematic, open-ended, essayistic, ambiguous in its relationship to history, uncertain in its political effect, resistant to formal closure, more inclined to ask questions than to provide answers, and ambivalent about the pleasures it offers.’7 These suggest two distinct, if related, positions. What is clear is that both satire and subversion are unstable in both their meaning and purpose and are dependent on both cultural and political context and time. Thus, over time, satire might lose its bite or gain more, depending upon its context, but the point remains the same: its meaning can change. To examine further both the strengths and the problems of satire in ceramics and its relationship to political subversion, I have selected two works. The first is from the Disfigurine series, (1998), by the American ceramicist, Justin Novak. Novak uses a mix of parody and the grotesque as well as ‘upending’ or overturning the sentimental social meaning of the ceramic figurine, an approach which might be regarded as a specifically ceramic trope of satire. The other work is called, Road Kill, (1998), an allegorical work by Bita Fayyazi, an Iranian artist, who lives and works in Tehran. Fayyazi’s is also a romantic approach which mobilises pathos and drama to produce the narrative. Allegory is a trope of satire to which the romantic element could be considered a counterpoint. Either way, the work is subversive politically even if not in ceramic terms. Justin Novak Novak uses a combination of parody and the grotesque to create a series of Disfigurines which critique the idealism inherent in the perfectly formed ceramic figurine, and articulates the damage done by trying to live up to such ideals, in particular with regard to body image. His is a confrontational vision, sometimes intensely painful, even cruel. One Disfigurine a very thin young woman, who might be beautiful but for her excruciating vulnerability, takes a vast ugly brutish looking pair of scissors, and extending one arm in front of her, carefully, and with a look of intense concentration, cuts, snips into the skin on the wrist of the extended arm. It is a devastatingly painful work to see. The more so because of the care she is taking to commit this act of extraordinary violence, which is carried out with such precision. It is an image of horror, but it’s still a small, beautifully made, ceramic figurine. It is the disjuncture between the violence of one and the innocence of the other that generates the shock which emanates from this work. Images: Justin Novak, Disfigurine from the series Disfigurines 1997-2006 ‘Ornamentation,’ says Novak, ‘is the meeting of beauty and order, but often it is an employment of beauty in the service of order, and specifically, of social order.’8 Novak provides his disfigures with ornamental plinths, which sharpen the contrast between the violence and what he calls the ‘dream-world’ of the figurine. In the same series, the young woman is sewing herself up with a needle and thread. Here there is an intimation of healing, but still peculiarly grotesque, and slightly brutal. Both works linger on feeling, the sensation of wounding, but there is a kind of masochism even about the second work, more than there is a healing quality. As a political indictment of a social culture, they are unforgiving, and they are also unforgiving in their exposure of what Novak calls the ‘sentimental affectations’ of the ceramic figurine. Geoffry Galt Harpham, in his Introduction to the Grotesque (1982) states that ‘the grotesque places an enormous strain on the marriage of form and content by foregrounding them both, so they appear not as a partnership, but as a warfare, a struggle.’9 This ‘enormous strain’ perfectly characterises Novak’s work. The cuteness of the figurine combined with its polar opposite in the case of the self-harming Disfigurines, is precisely what creates the tension which is so compelling in these works. Figurines indulging in violent, potentially suicidal or, in some of his other works, criminal practices, is a truly bizarre concept, and handled differently has comic potential. However laughter is not what we get from Novak’s extreme expressions of incongruity. It is the visceral nature of the work combined with the fineness of the making, which together amount to what Harpham calls ‘the sense that things which should be kept apart are fused together’ generating ‘a distinct feeling of repulsion.’10 The problem with this work, politically, is the deeply masochistic strand, to the extent that the social critique is potentially hijacked entirely, particularly because of the pale fragile prettiness of the work which paradoxically, is also part of its power to shock, but also because the pretty fetishising in Novak’s work could be said to perpetuate the very condition it seeks to critique – there is a hint of pop star romanticism in it. This is where I am suggesting that a satiric approach can undo the very critique it sets out to make. Dustin Griffin argues that this openness is inherently part of the satiric discourse, part of its resistance to closing down an argument11. This work certainly conforms to every definition of satire, but I am more doubtful about subversion. The ceramic prototype is subverted, certainly, but politically it has a baleful quality consistent with the masochistic values of the beauty industry it attacks. As a feminist critique which, in principle at least, it should be, it is uncertain. Bita Fayyazi Road Kill (1997), is a collection of dead, road-killed dogs made from terracotta clay and fired. I interviewed the artist about this work last time I was in Iran, in 2008.12 The numbers of dead dogs equate to the numbers of cars and carelessness of the drivers. She equates this with a general disregard and lack of care, in the society she inhabits, for both life and nature. Dogs in Shia Islam are also nejes, which is translated as unclean, defiled, or untouchable. They are widely regarded with fear and disgust. Fayyazi collected the dead dogs, kept their corpses at home and made clay sculptures of them. She showed the ceramic corpses in numerous locations around Tehran and photographed them all. She eventually buried both the real corpses and the sculptures, in a ceremony which she filmed. She now shows the film and the photographs, most recently in 2005.13 The entire process challenges Iran’s social mores and norms, very profoundly. It is also an act of opposition to religious doctrine. In a theocratic dictatorship, this can have serious consequences. At the time she made the work, 1997, the very conservative, orthodox nature of the Iranian regime was beginning open up, so it is no coincidence that Fayyazi began to do public and performance work then. Since 2009 the regime has become much harsher and this kind of act now would certainly mark her out as mohareb, or enemy of god. Mohareb is an accusation which now attracts the death penalty, in some cases, and always results in imprisonment. By anybody’s definition then, this is a highly subversive work. It is also an extraordinarily moving piece of work. It does constitute a challenge to what counts as important and moral, and what is considered unimportant, and defiled. While Western European sensibilities might identify the use of pathos and the allegorical mode of story telling in this work as mildly eccentric, in Iran, now, the work would be seen in numerous different ways. Owning a pet dog has, in the last four years, become very fashionable among the dissident upper classes and cool among the dissidents of all classes, so it might now generate sympathy and interest. That said, there is still a substantial group of people who would find the notion of giving a dead dog a ceremonial burial, disgusting, offensive, grotesque and, of course, blasphemous. The basiji routinely arrest people with dogs.14

Images: Bita Fayyazi, still from the film of Road Kill, 1998 Fayyazi is compelled to exercise caution in the way she phrases any critique of the Iranian political or social establishment. Hasan Javadi, in Satire in Persian Literature, 1998, notes that satire emerges in Iran during ‘brief moments of democracy,’15 and press freedom.16 Referring to the period of the Islamic Republic, since 1982, he states that Iranian satiric critique tends to be ‘either shrouded in obscure symbolism, or told in the form of a timeless parable.’17 Certainly direct expressions of dissent are not tolerated, and any critique Fayyazi wishes to mount must be articulated through a system of metaphor, symbols and allegory. The subversive nature of this work, has, in the last three or four years, become much more pronounced, as has the sympathy it might also arouse. Conclusion I selected only two examples, the Disfigurines, (1998), and Road Kill, (1998), to allow a detailed examination in the context of a short paper. They are two of the outstanding examples I have encountered in ten years of studying satire in contemporary and historical ceramic work. In both works the meanings are in an almost constant state of flux even as their social and political contexts change. What this study has revealed is that subverting a ceramic form or type does not necessarily produce a political subversion and, similarly, that political subversion does not necessarily require any deconstruction of ceramic processes or form. Satire in ceramics as in any other art form may or may not be politically subversive and a deeper understanding of satire and its tropes might help to preserve the specifically political nature of subversion. Some examination of the literature of carnival, masquerade, the burlesque and of ‘turn-about’culture 18, might provide a more useful framework to understand the plethora of ceramic production that has emerged over the last decade, much of which involves the deconstruction of ready-made industrial forms, but particularly that of the figurine. The figurine, usually a human figure and most often female, presents its own political complications, not the least of which is when the ‘subversion’ could be considered anti-feminist or consistent with a misogynist dominant culture and therefore politically reactionary – which is the opposite of subversion. What is clear is that the simplistic discourse of ‘subversive ceramics’ needs to be expanded upon so we can at least be spared the absurd pomposity of every slight modification to a ceramic type being named as ‘subversion.’ Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 1 Edmund de Waal with Claudia Clare, The Pot Book, London, Phaidon, 2011. 2 Dustin Griffin, A Critical Reintroduction to Satire, University of Kentucky Press, 1994, p.1. 3 Gilbert Highet, Anatomy of Satire, Princeton University Press, 1962. 4 Linda Hutcheon, Irony’s Edge. The Theory and Politics of Irony, London, Routledge, 1994, p.2. 5 Highet, Anatomy of Satire, p.241. 6 Griffin, A Critical Reintroduction to Satire, p.6. 7 Ibid, p.4. 8 Justin Novak, 1998-2001, artist’s statement in support of Disfigurines, 2007. 9 Geoffrey Galt Harpham, Introduction to the Grotesque, Princeton University Press, 1982, p.7. 10 Ibid, p.11. 11 Griffin, A Critical Reintroduction to Satire, p.4. 12 Much of this section has been possible because of a number of wide ranging conversations I have had with the artist in Tehran from 2004-8 and email exchanges since. My sources since 2009 have all been Iranian refugees based in London with whom I maintain regular contact. 13 Rebell Minds Gallery, Berlin, Germany, 2005. 14 The basiji were originally a religious youth movement and volunteer militia. They now have legal powers of arrest. They are often referred to as the ‘religious police’ although they are not, strictly speaking, a police force. 15 Hasan Javadi, Satire in Persian Literature, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, USA, 1988, London, Associated University Presses, 1998, p.198. 16 Since the uprising in 2009, production of satire in both visual and literary forms has become far more common inside Iran as well as in the diaspora. The use of internet platforms, notably You Tube, and weblogs have facilitated this. It sill carries a huge risk for practitioners inside Iran, however. 17 Javadi, Satire in Persian Literature, p.198. 18 Andrew Wilson, ‘Grayson Perry: General Artist,’ in Guerrilla Tactics, Rotterdam, NAi uitgevers, 2002. |

|||||||||

Subversive Ceramics: On Satire and Subversion • Issue 15 |