Interpreting Ceramics | issue 15 | 2013 Conference Papers & Article |

|

||||||||||||

The Romance of Old Blue: collecting and displaying Old Blue Staffordshire China in the American Home c.1870-1938Anne Anderson |

|

||||||||||||

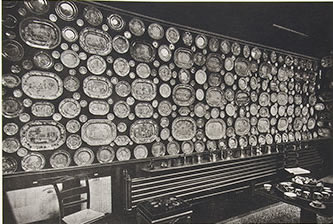

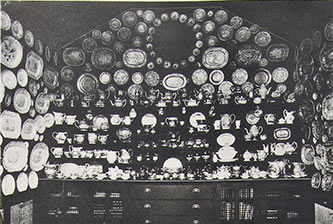

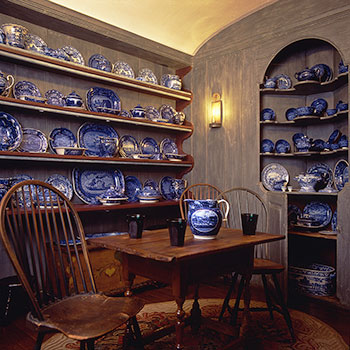

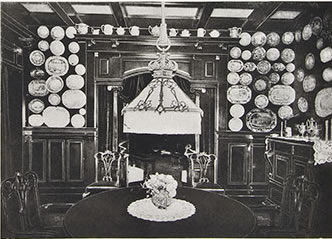

America was gripped by chinamania2 in the wake of the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. As historian William Cowper Prime acknowledged, collectors were keen to acquire both new products and antique specimens.3 A new pastime emerged, dubbed ‘china hunting’, with the attics of New England ransacked in search of Grandmother’s China. Although Old Blue Staffordshire was barely fifty years old it was repositioned as a desirable antique or collectable. Predating the Civil War, it evoked a romanticised Anti-Bellum, capturing the spirit of pioneer America. Originally a modest domestic commodity, Old Blue was now seen to enshrine the ‘everyday lives of our forefathers’. It also evoked childhood memories; for one American collector Old Staffordshire recalled ‘pie and cups of baked custard’.4 Such sentimental associations enraptured collectors; one besotted lady, her interest sparked by her grandmother’s china, cherished a plate featuring the Pittsfield elm as it recalled her birthplace. As the blue was very beautiful, she ‘wanted’ more specimens but confessed, ‘I suppose it’s because I’m a Daughter of the Revolution that I really care for most of them. They all belonged to somebody’s grandmother…in the brave days of the buff and blue’.5 Dubbed Anglo-American, being made in England but used in America, Old Blue Staffordshire was recast Americana, with both Richard Townley Haines Halsey (1865-1942) and Edwin AtLee Barber (1851-1916) recognising ‘this dark blue pottery’ would offer a valuable contribution to the history of the nation.6 But Americans were also captivated by its beautiful rich blue colour; Oscar Wilde’s (1854-1900) famous dictum ‘Oh, would that I could live up to my blue china!’ guaranteed its artistic credentials assigning Old Blue its place in the House Beautiful.7 Aesthetes lionised its decorative qualities; a teapot was now valued as a work of art rather than a utilitarian household object, as seen in George Du Maurier’s famous Punch cartoon ‘The Six-Mark Teapot’ (1880).8 Endorsed by pioneer collectors, who numbered James McNeil Whistler (1834-1903) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), Old Blue porcelain and pottery was now deemed not only beautiful but also culturally superior, signalling refined taste and gentility. By 1900 no self-respecting American millionaire would be without his so-called Hawthorn Ginger Jar; Henry Clay Frick possessed four. As Stacey Pierson observes, Oriental blue-and-white was no longer the preserve of ‘delicate, refined aristocratic women but rather prominent, wealthy men, usually, but not always businessmen’.9 Linked to the masculine sublime, Old Blue connoted distinction and, it is argued here, manliness, despite china’s longstanding feminine associations.10 Conversely, women were able to participate as serious collectors, acquiring rare views and makers, as the wares ornamented their homes. Mrs Marshall L. Hinman of Dunkirk, NY, created a china closet systematically hung with historical china; the serried ranks of plates and platters are arranged so densely they replicate wallpaper (Fig 1 and Fig 2). Pieces of ‘rich blue Anglo-American Staffordshire’ were ideal for a Colonial style dining room, enhancing a wall, mantel or plate rail, opined Walter Alden Dyer (1878-1943), who penned many books on the art of collecting.11 For Mrs Alice Morse Earle (1851-1911), one of the earliest authorities, dark blue Staffordshire provided a ‘rich a point of color’ that shamed its weaker rivals; she understood Oscar Wilde’s longing.12 Failing this, a corner cupboard with Colonial glass doors would keep one’s china ‘as your grandmother did in the old poke-bonnet days’.13 Blue Staffordshire was recast as America’s ‘Colonial blue’, the decorator’s choice for ornamenting the House Beautiful and House in Good Taste.14 Old Blue was prized, as in England, as ‘a fascinating style of decorating’.15

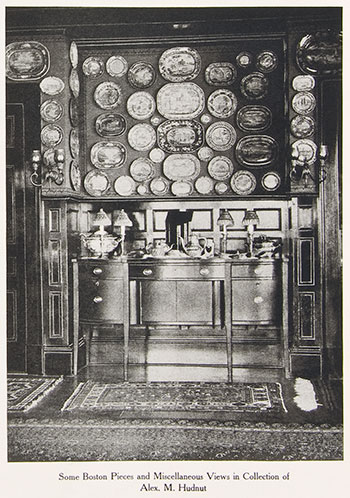

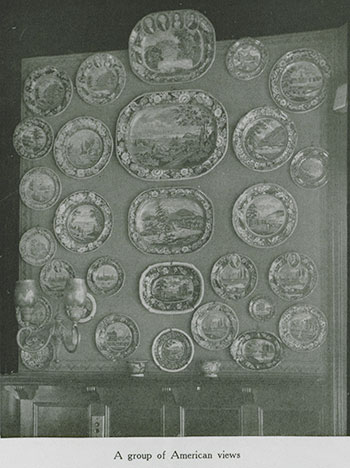

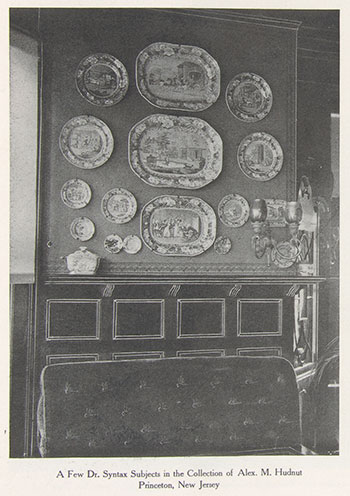

Americans are still fascinated by the ‘pictorial table wares of their forefathers’, with innumerable books and articles on makers and views, but hitherto no one has attempted a historiography of its rise to eminence or considered the pioneer collectors, their collections or how the wares were displayed in American homes.16 The mania for Old Blue Staffordshire peaked in the 1920s, stimulated by two remarkable auctions. Following his death, George Kellogg’s collection came under the hammer in 1925. Alexander Hudnut consigned his FN28 collection in 1926, perhaps prompted by the high prices achieved the previous year. Hudnut established his credentials in a series of articles for American Homes and Gardens, which reveal the leading players, their preferences and how their specimens were displayed. 17 The collections illustrated by Hudnut have for the most part been dispersed; they offer valuable insight into collecting practices and modes of display. Apparently the attraction of Old Blue Staffordshire was two-fold; its historical value and decorative effect. Both male and female collectors were keen to complete series, such as Mayer’s Arms of the States, Ridgway’s Beauties of America or a full set of New York views, while realising the potential of Old Blue for decorating their homes.18 Collecting Old Blue Staffordshire is framed here within discourses on nationalism, sentimentalism and aestheticism; it was sought for its pictorial representations, its associations and its beautiful colour. Positioned as an ‘object of desire’, collection forming was legitimised by academic study, with acquisitions based on completing series and displayed according to museum practises (by factory, view or subject) despite being located in a domestic environment. Here it was used to create a spectacular visual effect, conspicuously within the ‘masculine’ dining room. Such displays stimulated Old Blue mania and provoked intense rivalry amongst male collectors; sale catalogues are used to reconstruct the Kellogg and Hudnut collections as these assemblages established a hierarchy of aesthetic and financial values predicated on the rarest views and the best blue. The discussion concludes with an appraisal of William Randolph Hearst’s Anglo-American views, perhaps the finest assemblage of its kind ever formed.19 It is argued that while ‘historical character’ added patriotic, sentimental and financial value to ‘good pieces of blue’, its decorative impact lay in its hue.20 China Hunting Blue Staffordshire rose to prominence in the ancestor-conscious 1890s; Mrs Earle belonged to the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Society of Colonial Dames. Such patriotic societies had aroused pride in ‘ancestral possessions’. Jane W. Guthrie claimed to be a true son or daughter of America required worshipping at the shrine of old blue and white; ‘ownership of an ancestral possession of this kind is equal to a patent of nobility nowadays’.21 As ‘permanent pictures’ of a vanished America, Old Blue Staffordshire was destined to attract the local historian; Prime foresaw this new interest, first drawing attention to Old Blue in his preface to The China Hunter’s Club (1878) by his sister-in-law Annie Trumbull Slosson. Despite its lowly status, compared to Dresden and Sevres, the wares of Clews and Ridgway preserved America’s first steamboats and railways, as well as the portraits of distinguished statesmen, soldiers and sailors. In memorialising both the triumphs of war and peace, such ceramic specimens would ‘rank in historical collections with the vases of Greece…men will say ‘These show the tastes, these illustrate the home life, of the men and women who were the founders and rulers of the American Republic’.22 Moreover, acquiring these historical documents was not yet a ‘costly pleasure’, according to Mrs N. Hudson Moore (1857-1927), author of The Old China Book (1903); Old Blue Staffordshire was both affordable and plentiful. Ardent collectors numbered a busy doctor, an editor, a butcher, an actor, a schoolteacher and ‘dozens of women of leisure’ some with wealth and some with none. Yet all rejoiced in the cultivation of an interest which provided ‘agreeable food for reflection and which stimulates as well as rests’.23 Professional men, lawyers, doctors and academics, accumulated fine collections but women also entered the fray, notably Mrs Emma De Forest Morse of Worcester, Mass., whose collection was presented to the American Antiquary Society in 1913. Americans were enthralled by the chase and the quest for rarities; Kellogg was fond of motoring and scoured the country searching for pieces to make his collection more complete. The China Hunter’s Club offered the first guide to the emerging sport, being a record of discoveries, chiefly in New England, with ‘veritable histories attached’.24 The China Hunters organised expeditions in ‘search of plunder’; their ‘ceramic adventures’ were recounted at regular meetings. In this way, as Talia Schaffer observes, each discovery was ‘mystified into a moment of sentimental and aesthetic affirmation’.25 As the collector is a temporary guardian, ownership accrues as attested descent or provenance, Grant McCracken’s endless conversion of ‘ancestors into objects’ and ‘objects into descendants’26; Schaffer recognises this as a ‘symbolic genealogy’.27 Cast as mementoes they also enshrined personal reminiscences, allowing the possessor ‘to look back with fond recollection to the day when you scraped together enough money to buy your first piece of Old Blue, and when the handling of it will produce a sensation not unlike the hearing of an old love-song'.28 Mrs Earle’s ‘dear old china loves’ were ‘gathered treasures of her happy china hunts’; china hunting was a ‘midsummer madness’, with every ‘china captive’ a ‘glorious idealized token of long warm halcyon days too quickly passed, of “yesterdays that look backward with a smile”’.29 Earle claimed that her ‘china quests’ had taught her insight into human nature, love of her native country, knowledge of its natural beauties and landmarks, familiarity with history, particularly noble military and naval heroes, and fostered the study of the customs and traditions of early Americans. The China Hunter’s Club highlighted the historical value of Blue Staffordshire; a club member Mr Whitney, who had scorned old china as ‘monstrosities, grotesques and horrid objects with glittering surfaces’, had been converted to the cause by a Washington pitcher with an old map of America.30 Compiling the first list of views on Anglo-American pottery, Whitney commended this ‘once cheap crockery... whose worth consists of their great beauty of color as well as their historical associations’.31 Earle’s China Collecting in America (1892) provided a list of the views she had so far discovered; she also explained their significance. Where possible she identified the English manufacturer responsible for a view or series of views. She had the advantage of being able to study the Morse Collection of American Historical Pottery, formed by her half-brother Edwin A. Morse and his wife Emma De Forest Morse. Her sister Frances Clary Morse, noted for Furniture of the Olden Time (1910) also collected Old Blue Staffordshire.32 Barber’s Anglo-American Pottery (1899) was the first monograph to offer a ‘scientific’ classification according to maker, based on both trademarks and border designs that signified authorship.33 Further encouragement came from Halsey’s Pictures of Early New York on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery published almost simultaneously. This was illustrated with specimens from his own collection plus examples supplied by Eugene Tompkins, Rev E.L. McClure, Miss Florence Chauncey, Mrs E DeF. Morse and Miss Frances Morse. Halsey’s account was a scholarly attempt to ‘recall certain memories of the past’ when the nation initiated ‘its career of social progress’; views commemorated great feats of engineering, including the opening of the Erie Canal.34 Although beautiful produced, photogravures bringing out the superb blue colouring, this limited edition of 268 copies was for the rarefied connoisseur. In The Antiquers, Elizabeth Stillinger lauds Halsey as a champion of American antiques, especially their artistic value; apparently he made the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art a reality.35 Under his tutelage collecting American antiques went from an amateur pursuit to a fundamental concern of major institutions. As Americana Blue Staffordshire was now the object of learned enquiry; Old China, a monthly periodical, primarily devoted to historical Staffordshire, claimed to have over 3000 subscribers. Edited by Samuel Robineau, the husband of artist potter Adelaide Alsop-Robineau, the magazine ran from October 1901 to Sept 1904; contributors included Barber, Dr Christopher J. Colles, who collected British views and Mrs C.C. Varney.36 Founded in 1922, the magazine Antiques offered collectors both historical information and values for Blue Staffordshire; during the period 1922-37, editor Homer Eaton Keyes noted the magazine had published some thirty-five articles and innumerable notes on historical wares.37 The Antiquarian, edited by furniture expert Esther Singleton, also carried numerous articles on Blue Staffordshire.38 But it was Ada Walker Camehl’s The Blue China Book Early American Scenes and History Pictured in the Pottery of the Time (1916) that captivated the collector’s imagination. Focusing on specimens illustrating the history of the nation, Camehl took the reader on a ‘Tour of the Land’, the cities and buildings of Old New York and the Philadelphia of Penn. With America at war, Blue Staffordshire simultaneously fuelled patriotic feeling and nostalgia for the ‘good old days’. Beautiful Old Blue dishes, the ‘pictured memorials of early America’ were to be placed among the ‘authentic documents of history’.39 Old Blue Staffordshire Blue Staffordshire, a class of printed earthenware produced exclusively for the trans-Atlantic market c.1815-40, was originally destined for daily use in the American home. The bright azure blue colouring was chosen as it was already well established with American housewives familiar with Chinese Nankin wares and was ‘the richest form of cheap decoration’ that covered imperfections.40 By c.1818 a richer darker blue had been introduced; although this never ousted the ‘royal’ hue, it was produced by a number of manufacturers for about 10 to15 years. This richer hue was achieved by printing a negative pattern; the subject was left white while the background was filled with blue. After 1830 this dark blue was superseded by lithographic reproductions in lighter colours, considered, by later collectors, artistically inferior to those printed from a deeply cut copper plate.41 Retailer’s order books and archaeological excavations show that the darker blue wares enjoyed a great vogue from c.1820 to 1830.42 In 1818 a Boston wholesaler and retailer specified his blue wares were to be as dark as possible.43 Ninety years later Alexander M. Hudnut, a connoisseur of Old Blue, commended those shades that were both beautiful and extremely rare; the collector’s goal was to possess a few specimens ‘perfect in color’.44 Dyer recognised Old Blue’s ‘chief claim to beauty’ was its ‘truly remarkable colour’.45 For Halsey the most valued shade was a deep rich blue that rivalled ‘the priceless productions of the Orient’.46 Prime concurred, declaring ‘old Staffordshire crockery’ was a superb blue, equalling or surpassing the Chinese tints.47 Mrs Earle enthused this arresting tint, called by the Chinese ‘the light of heaven’, was unexcelled and inimitable; Blue Staffordshire was ‘a never-ceasing delight to the eye’.48 During the ‘Era of Good Feelings’ (c. 1816-1824) patriotism favoured war heroes and founding fathers as subjects.49 In 1824 the historic landing of the Revolutionary War hero Marie-Joseph Lafayette in New York was recorded as a print, transferred to earthenware and shipped to America in less than six months; apparently British potters never allowed national pride or patriotism to stand in the way of their commercial interests.50They commemorated the revolutionary war (Battle of Bunker Hill) and the War of 1812 (The Constitution’s escape from the British squadrons after a chase of sixty hours) as well as heroes of the nation-George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, De Witt Clinton, and Benjamin Franklin- on plates and pitchers. Given lingering anti-British feeling Jamestown, York Town and Williamsburg, Virginia are notably absent.51 Rather the views underpinned an emerging mythology of American nationhood. Wood’s Landing of the Pilgrims, not only commemorated the first imprint of ‘the footsteps of those who gave the empire birth’, but also marked the 1820 bicentennial banquet at which Daniel Webster (1782-1852) delivered his celebrated Plymouth Oration.52 Historic scenes and heroes fired antiquarian interest; Romanticism ushered in natural beauties, notably Niagara Falls, the Hudson and Schuylkill rivers, and the developing cities of New York, Boston, Baltimore and Philadelphia. The ‘Beauties of America’ by J. & W. Ridgway of Hanley memorialised public buildings from Massachusetts to Georgia: the Boston State House, New York City Hall, Savannah Bank and many churches, including the Octagon Church Boston (New South Church), an American Beauty swept away in 1868 in the name of progress. In search of new subjects, artists headed for the Mid-West, sketching Detroit, Louisville, Sandusky and Columbus. 53 The potters being unfamiliar with the actual views frequently marked pieces with the wrong titles; The Old Capitol Building at Washington inadvertently became Mount Vernon seat of the Government of the United States. Apparently, for many collectors, this only added to the piece’s charm. Old Staffordshire often provided the only surviving pictorial record of a vanished view or building; three designs commemorated the Nahant, near Boston, one of America’s most fashionable hotels that was destroyed by fire in 1861. Mrs Hudson Moore noted Wood’s Castle Garden, Battery platter had ‘many curious little details’ capturing a lost era.54 The ‘Four Hundred’, the cream of New York society, had come here for an afternoon walk to enjoy the sea breeze; the Battery, so-named as the English stationed guns there, retained nothing of its original character. Views were taken from prints, after drawings by American and European artists, in publications dealing with the history and topography of the United States. American historical china not only captured a local scene but also preserved the art of foreign and native delineators.55 The views of Dublin born William Guy Wall were rapidly transferred to earthenware, firstly under the auspices of Andrew Stevenson, who is credited with sixteen American views and then Clews: New York from Brooklyn Heights appeared in Walls’s Hudson River Portfolio.56 Wall’s New York from Weehawken was prized by collectors as a rarity, selling for $1225 at the Robert L. Forrest, Philadelphia sale in 1912.57 This unheard of price, provoked by its clear impression and beautiful shade of blue, did more ‘to spread the fame of Staffordshire Blues ...than any other incident in its history’.58 Hudnut deprecated such absurdly high prices but clearly there was no limit to the enthusiasm and vagaries of the collector.59 In this instance, George Kellogg of Amsterdam, New York (1851-1925) took the prize; ‘there never lived a more enthusiastic love of the old Blue’.60 The financial value of historical Staffordshire escalated rapidly in the opening years of the twentieth century; Mabel Woods Smith attempted to aid the novice in the field by compiling a price guide, based on saleroom results for Anglo-American historical china over a four-year period from 1920 to 1923.61 The first landmark auction occurred in1903; the collection of A. Melrose Burritt of Waterbury, Connecticut, was remarkable for many ‘proof pieces of rare subjects in brilliant blues’.62 Two leading contestants emerge at this auction: Kellogg and William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), the infamous newspaper magnate. Over the next two decades Kellogg and Hearst, for whom money appeared to be no object, built the finest collections; their rivalry undoubtedly stimulated the rising prices. Hearst eventually took the upper hand; at Kellogg’s 1925-deceased estate sale he was the principal purchaser, securing the infamous New York from Weehawken.63 American colonial fervour soon sought out English views; Mrs Hudson Moore lamented, specimens previously ‘picked up for a song’ were now soaring in price. Picturesque castles, cathedrals and country houses, famed for their builders and owners, possessed the ‘glamour of antiquity’.64 Blenheim was almost genuine Americana, as its chatelaine was a Vanderbilt! Wood’s London views, Country Seats, and English Cities and now graced American walls and shelves. French and Italian views could memorialise or fuel aspirations for a Wanderjahr; ‘Wanderlust’, the craving for travel, transforming views into souvenirs, embodying a past experience. However, the American passion for Old Blue went beyond both American, British and European views; for many a collection of historical china was not complete without the Dr Syntax, David Wilkie and Don Quixote series, which were esteemed as beautiful, decorative and rare.65 Clews reproduced seven paintings by Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), a contemporary of J.W.M. Turner, in dark blue china; The Valentine, Christmas Eve, Letter of Introduction, Escape of the Mouse, Rabbit on the Wall, Playing at Draughts and the Errand Boy, deemed the scarcest platter. Although coarse in sentiment Mrs Hudson Moore praised them as ‘ornamental on the wall’ and ‘a beautiful piece of colour’.66 Clews’ Don Quixote series also pandered to ‘popular taste’: this dinner service, composed of many shapes, transposed to pottery engravings by Robert Smirke and Charles Westall.67 Walter Randell Storey, known for his expertise on interior decorating, concluded proof pieces were not necessary to enjoy the ‘double pleasure’ of the Don Quixote series; firstly the ‘beauty of color and charm of design’ and secondly ‘the delicious satire on life and the kindly human touch of Migel de Cervantes’.68 Although failing to rival the value of the Syntax series, in 1928 dealer L.J Buckley recorded a service of twenty-six Don Quixote pieces selling for $1,875, averaging far more than when sold separately.69 Hudnut rated the Syntax Views ‘among the most perfect specimens of dark blue printing’.70 With illustrations by Thomas Rowlandson, Dr Syntax in Search of the Picturesque (1812) tells the story a schoolmaster who escapes his nagging wife by embarking on an adventurous sketching tour. While not a literary masterpiece, the fable was very popular; it ran through five editions in twelve months. The Second Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of Consolation (1820) chronicled further adventures following the death of his wife; Syntax is entertained by gypsies, captured by highwaymen and sold a blind horse that rushes madly into a stage coach, all of which were transferred to Old Blue. After these mortifying experiences Syntax decides to find a bride in Third Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of a Wife (1821). The three volumes contained seventy-nine illustrations; R. and J. Clews reproduced around half on Blue Staffordshire. Scenes were printed on platters, plates in different sizes, gravy boats, ladles and tureens. Collectors welcomed these many variants, as they provided the opportunity to fashion a distinctive arrangement.71 Willow pattern inevitably joined the ranks; the Robineau collection had Willow by Riley, Minton and Stubbs.72 One American gentleman, who resided at The Willows, claimed to possess three thousand pieces complimented by wallpapers, bedspreads and draperies; ‘Surely there may be too much of a good thing’, exclaimed Mrs Hudson Moore.73 For Dyer, whose ‘indifference’ to Willow pattern was little short of contempt, it was ‘overdone’; no pattern was so widely or profitably reproduced. Yet many regarded it as the ‘sine qua non’ of every well-regulated household.74 When the British East India Company ceased importing Chinese porcelains in 1792, indigenous manufacturers were spurred into action producing blue printed earthenware in bulk for the home and overseas market. Willow pattern purloined traditional Oriental motifs; the design features a willow tree, a bridge with three figures, a boat, a teahouse, a fence running across the foreground and the two ‘love birds’.75 By 1814 Willow had become the cheapest transfer printed pattern, retaining this position throughout the 19th century. There was something for every pocket, as Willow was the ‘poor man’s blue-and-white’; earthenware dinner services decked the kitchen dresser, while bone china cups and saucers graced the drawing-room china cabinet. American designer Candace Wheeler imagined a kitchen as a ‘symphony’ in blue, with a narrow shelf around the room carrying a row of blue willow-pattern plates, a dresser hung with a graduated assortment of blue enamelled sauce-pans and a floor laid in small diamond-shapes of blue-and-white, like a mosaic pavement.76 All this would be ‘a joy to behold’. Evidently the passion for Old Blue Staffordshire was not exclusively tied to the view; hue was the important factor when considering an ornamental display in the home. Ceramics as WallpaperThe desire to form china closets may have been provoked by exhibition displays; the 1876 Centennial Exposition featured a New England Kitchen. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, also known as the Atlanta Exposition, featured a New York Colonial Room that was a ‘perfect study in blue and white’, according to Jane W. Guthrie.77 With walls papered in blue and white and hung with historic platters, the ensemble was completed with drapery and hangings of finest sea-island cotton dyed an ‘exquisitely harmonious blue’. To ‘form an attractive mural decoration’, Hudnut considered the perfect collection would contain around 300 pieces.78 But, as Barber’s ‘Directory of Collector’s’ informs us, some far exceeded this quota; Mrs H.M. Johnston of Brooklyn, New York gathered some 800 pieces of Colonial china, Dresden and Oriental wares; Edward S. Brewer of Longmeadow, Mass amassed a general collection of around 2000 specimens, while Mrs Harriet Brownell of Providence, RI, succumbed to 1200 teapots.79 Destined for the dining room, library and study, the quintessential masculine retreat, Old Blue would be claimed as ‘manly’; it was a welcomed anecdote to the Dresden Shepherdess and Rococo Sevres vases that smothered the boudoir and drawing room. For Alexander Hollingsworth, author and connoisseur, a room tastefully adorned with Blue China elicited a sense of repose and encouraged contemplation; ‘thank God that there is at least one nook in the world wherein you may find that true joy which a fancy, Bridecake style of decoration can never bring’.80 Old Blue was far from effete; valorising its colour as ‘Sublime’, a concept gendered masculine in Edmund Burke’s Treatise on the Beautiful and the Sublime (1757), recuperated the collecting of Old Blue for the male sphere. At Chestertown, Southampton, NY, Henry Francis Du Pont (1880-1969) experimented with colour schemes and dramatic staging; Old Blue Staffordshire was arranged in the Library of his American House.81 These pieces would find a permanent home in the Blue Staffordshire Room at Winterthur, Delaware his ancestral home soon to be transformed into a museum (Fig 3). Here the dining room cupboards were ‘filled with the ceramics that intrigued Du Pont’82; both a collector and decorator Du Pont realised the potential of ceramics to compliment his Colonial furniture. In all its myriad forms, Old Blue offered diversity. As The Art Amateur, noted being akin in colour all the objects were on ‘friendly terms’ and ‘yet the blues and whites are so varied in tone and the patterns so different…that there is little danger of monotony in the effect’.83

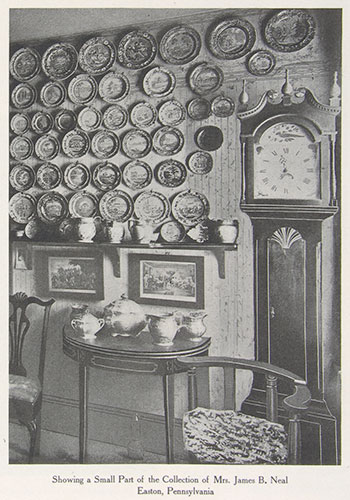

The plate shelf became an essential architectural feature in the dining room, its mission to hold pieces of china that were worthy from an artistic or historical point.84 The position of the plate rack was lowered to enable a better appreciation of the view. Interior decorator Alice M. Kellogg suggested china closets built into or against the wall as another means of bringing interest into the dining room. Thus Old Blue could be massed to create a spectacular effect, replicating a late 17th-early 18th century china ‘closet’ or ‘cabinet’, arranged in garnitures on cabinets and mantels or admired as a single specimen, being judged on its intrinsic merits and antiquarian value. Charles L. Pendleton of Rhode Island (1846-1904)85 and Arthur Merritt, DD, of New York devised china closets:

Such closets may have been inspired by Whistler’s Peacock Dining room (Harmony in Blue and Gold, 1877) originally a showcase for Frederick Leyland’s Chinese Old Blue; the Peacock Dining Room caused a sensation when transported to Detroit by Charles Lang Freer in 1904. But Freer was not the first to have a Blue room in Detroit; Deming Jarvis, joint Director of the Michigan Carbon Works, had filled his dining room with four hundred pieces by 1901. This enthusiastic American collector saw his Old Blue as ‘essentially decorative’; a carpet was designed and woven in China to ‘harmonise with the ware which is the splendour of the room’.87 Other collectors were more diverse in their choice of Old Blue. In Dr Hammond’s New York residence sideboards were loaded with Old Delft, Chinese, Japanese and even Siamese wares; plates, dishes and plaques formed ‘a natural and very suitable ornamentation for a dining room’.88 The impression of ‘an old baronial hall’ was conveyed; in W.R. Hearst’s baronial dining room at Hearst Castle his guests dined on Booth’s Willow pattern. The ‘older fashion’ of arranging bric-a-brac on the mantel or tables was ousted by the ‘newer style’ of lying ‘against the wall’ on a plate rail or pottery shelf.89 But, warned Kellogg, placing was all-important; while a low shelf added ‘cosy feeling’, placed too high the contents was rendered insignificant, losing the pleasure of a critical examination of the china. In choosing the china, it was important not to lose sight of the decorative point; the selection should ‘arrest the attention pleasantly and hold it by agreeable colour or artistic design’.90 The arrangement of plates, platters and pitchers on a plate shelf tested artistic knowledge. It needed an eye for colour and a true sense of correct lines, shapes and proportions. Pieces of different heights and shapes should alternate, while cups and saucers could be grouped with the cups suspended from hooks. Wall coverings were to be carefully selected to compliment and bring out the dark blue of the china; certain shades of buff were considered the best. Plates primarily acted as pictures; densely hung they substituted for wallpaper. Collectors engaged in a variety of collecting and displaying practices, opting for a maker, specific views or a preferred shape (plate, platter and pitcher). Some preferred to mass pieces by factory, regardless of the views: Enoch Wood & Sons, Stubbs, Clewes and Mayer were favourite makers. But grouping by factory was more technical, appealing to the connoisseur. Others looked for scenes of Boston or New York; some were happy with one specimen while others looked for permutations by different makers: the Park Theatre, New York was printed by Ralph Stevenson and John Geddes on a ten-inch plate and by Stubbs on a six-inch plate. As the majority were not well informed, Hudnut argued the best classification was by locality; an arrangement that appealed to the eye met with more ‘general appreciation’.91 His own display grouped together New York and Boston views. Flat shapes were the most desirable as they could be hung, forming ‘an attractive mural decoration’.92 Specimens were hung densely, covering walls in serried ranks, plates and platters ordered by size; Mrs Marshall L. Hinman’s mosaic pattern formed with round plates and squared platters interspersed with ‘cup-plates’ is exceptionally dense (Fig 2). Miss A Josephine Clark, South Framingham, Mass, was reputed to have amassed 400 cup-plates, apparently used to stand a cup on when tea was poured into the saucer to cool. Measuring some 3½ ins across, according to Barber these were remarkably difficult to obtain and ‘worth their weight in gold’.93 Blue Staffordshire Mania In his articles for American Homes and Gardens, Hudnut identified the leading players and evaluated their collections. Mrs Emma DeForest Morse, one of the most energetic and successful collectors, accomplished the ‘almost impossible task’ of finding 280 varieties of dark blue historical ware deemed by Hudnut the finest in America. With her husband, Edwin, who had been severely wounded at Gettysburg, Emma Morse began to collect antique furniture and china around1885.94 She soon devoted her energies to acquiring Staffordshire pottery with American scenes, aiming to obtain every known view, in dark blue if possible and failing that in light blue, brown, black or pink. The Morse collection of American Historical Pottery was presented to the American Antiquarian Society in 1913.95 These were not the first specimens of Blue Staffordshire to enter a public collection; as early as 1898, Guthrie notes the Field Columbian Museum, Chicago and the Pennsylvanian Museum, Philadelphia were already rich in specimens of historical platters, while the loan collection of the Bostonian Society had been enhanced by the artist Samuel B. Dean, considered a noted pottery expert, with a La Grange platter featuring La Fayette’s Chateau.96 Larger bequests followed; Mrs Abraham Lansing of Albany (Catherine Gansevoort Lansing [1839-1918]) gave thirty to forty pieces to the Metropolitan Museum in 1910.97 Catherine Lansing, founder of the Gansevoort Chapter of the Daughters of the Revolution, was also a benefactor of the Albany Institute of History and Art, which received the James Ten Eyck gift of some 5000 pieces of English ceramics in 1910. The New York Times declared this collection, said to have cost $100,000, was beyond duplication; while the ‘dark blue coveted by collectors’ was only a small fraction of the gift, Ten Eyck had procured nine of the prized Arms of the American States. 98 Collectors hoped to find a full set of the Arms of the American States manufactured by Thomas Mayer, which numbered the original thirteen colonies.99 Emma Morse acquired eleven specimens: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Rhode Island, and Virginia, only lacking Pennsylvania and New Hampshire. Mrs H.M. Soper of New York tracked down all the Arms of the States bar New Hampshire. In 1939 noted authority Ellouise Baker Larsen lamented ‘New Hampshire in deep blue...has not been discovered, but it may eventually be found’.100 Pennsylvania remains the scarcest in the series. In addition to dinner sets, the Arms of the States can be found on washbowls and pitchers; Connecticut has the distinction of being represented on a gravy boat, cover and tray. The Old Capital at Albany washbowl and pitcher was without doubt Mrs Morse’s most valuable specimen, as it carried portrait medallions of Peter Stuyvesant, Chancellor Kent, Washington and Clinton. Blue Staffordshire with portrait medallions, numbering from one to four, were revered. Mrs Hudson Moore, who declared these specimens to be ‘the highest expression of old blue’, illustrated a R. Stevenson & Williams jug featuring Rochester Aqueduct Bridge and Entrance of the Erie Canal into the Hudson at Albany with Washington, Lafayette, Jefferson, and Clinton.101 The building of the Erie Canal, which connects Lake Erie with the Hudson River, a distance of 363 miles, was deemed a great enterprise worthy of commemoration. Plates also eulogised De Witt Clinton, Governor of New York, who was credited with realising the project. Other engineering feats were also memorialised; the Fairmount Dam and Water Works, Philadelphia (1812-15), a popular tourist attraction and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the first ‘common carrier’ initiated in 1828.

Mrs Marshall L. Hinman of Dunkirk N.Y. possessed a ‘treasure house’. Amanda Josephine (1844-1908) apparently sought solace in her old china; after the marriage of her only daughter in 1898 the collection grew rapidly.103 Soon a museum had to be built to accommodate it. She did not restrict herself to just Old Blue; historical wares in all colours plus English views and lustre ware jugs created a bright mosaic. Plates were hung on dull red burlap ‘with mathematical accuracy’, everything ‘suggestive of order and symmetry’.104 Photographs show a staggering range of pitchers, jugs and other shapes arranged on shelves, an array of small cup-plates forming a perfect circle on the wall. (Fig 2) An inventory taken in 1985, when the collection was gifted to the Los Angeles County Museum (LACMA), suggests Hinman was less concerned with collecting rarities; she possessed only four Arms of the States- New York, Rhode Island, Delaware and South Carolina.105 However, she was determined to acquire early American subjects possessing twenty views of New York (in different colours) and fourteen of Boston; the collection also included views of the Erie Canal, Albany, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, the Hudson River and the Mid-West. Given her husband founded the Brooks Locomotive Works, she naturally took an interest in ‘early developments in the field of transportation’; she owned both Baltimore and Ohio Railroad views, ‘inclined plane’ and ‘passenger train’, plus the Fulton Steamboat, Chancellor Livingston Steamboat, Union Line Steamboat and Chief Justice Marshall Steamboat. She possessed all the Wilkie views, plus specimens from the Dr Syntax series. With seventy-three English views, Hinman appears to have valued decorative effect over historical significance; colour and variety appear to guide her selection. In 1917 her daughter Blanche Garland loaned over 700 pieces to the Los Angeles Natural History Museum; in 1923 International Studio described the collection as the finest in the West and one of the greatest in the whole country.106 The habits of Hudnut’s male collectors did not differ from his female aficionados. Both sought rare patterns by different potters in various sizes and shapes; Mr Eugene Tompkins’ (1830-1909) dining room walls were just as densely hung, creating a spectacular display of Old Blue (Fig 5). Tompkins was prominent in theatrical circles, initially as theatrical manager under his father Orlando Tompkins, owner of the Boston Theatre. After the death of his father in 1883, Tompkins directed the Boston Theatre until his retirement in 1901. In addition he had interests in New York, leasing the Fifth Avenue Theatre in 1887 and, with E.C. Gilmore, the Academy of Music.107 Tompkins’ ‘truly marvellous’ collection of 242 varieties transformed the dining room of his Boston mansion into a china closet; an ‘example of artistic grouping’, plates and platters graded by size were hung on the walls, galleried racks over the doors carried jugs and platters, while a glazed cabinet provided a safe haven for more delicate cups, hung by their handles, and saucers. 108 His great rarities numbered a Junction of the Hudson River and the Sacondaga, and a View of Governor’s Island.

George Kellogg ‘managed to gather unquestionably the finest and most complete collection of Old Blue Staffordshire in the world’.109 (Fig 6) His deceased estate sale numbered 368 pieces of Old Blue, of which Hearst purchased the finest specimens.110 Kellogg, with his brother Lauren, owned and ran Kellogg and Miller, Amsterdam, one of the largest linseed oil refineries in the world. Kellogg and his wife Susan Chase came from well-established American families, their ancestors dating back to the Revolutionary era. It was his wife’s purchase of a States plate that inspired Kellogg’s quest.111 This was more than a collection of china; it was ‘a picture story of America when the country was young’.112 Kellogg’s purchases did not come cheaply; the record $1225 price he paid for New York from Weehawken was not eclipsed until the Arms of Connecticut set a new record of $1800 at his deceased estate sale. His purchase of Constitution and Guerriere for $75 in 1903 was considered ‘well paid for by the knowing ones’.113 Kellogg’s Harvest Home, the scarcest Syntax platter, was obtained at the Burritt sale for $470; it took money as well as unfailing interest and constant devotion to build up a complete collection.

Kellogg assiduously sought all the ‘wonderfully instructive’ American subjects; 27 specimens featuring Lafayette, Enoch Wood’s Erie Canal trilogy as well as views along the Hudson, Niagara Falls, Lake George and Trenton Falls. He was partial to scenes of New York; City Hall, Park Theatre, St Paul’s Chapel, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Columbia College and Castle Garden, Battery were all acquired. These views set record prices in 1925; Esplanade and Castle Garden went to Henry Woods, acting on behalf of Hearst, for $1,100, who also secured the New York from Weehawken platter for $810.114 Kellogg gathered an almost complete run of Dr Syntax, including a cheese dish decorated with many different scenes considered ‘the only one in existence’; Mrs D.C. Howe acquired this for $360. But G.E. Comstock secured Harvest Home with a bid of $300. The two-day sale realised $30,490. Perhaps encouraged by these high prices, Hudnut placed his collection on the market the following year. An old Princeton family, Hudnut’s father had founded the celebrated drugstore in the Herald Building, New York (218 Broadway), a landmark between Fulton and Ann Street; his soda fountain was frequented by ‘hundreds’ of New Yorkers.115 Upon retirement in 1889 Hudnut senior’s fortune was estimated at a million dollars.116 His son, a broker by profession and painter by inclination, had the means to develop an important collection of Americana, encompassing furniture, notably pieces by Duncan Phyfe and William Kerwood, and works by the American artist John Francis Murphy, ranked at the time alongside George Inness and Homer Martin (Fig 7).117 He was also a noted bibliophile.118

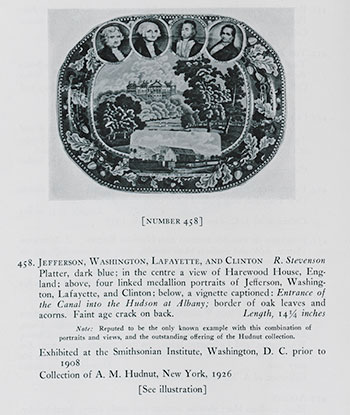

When sold in 1926 the Hudnut collection numbered 236 pieces of Blue Staffordshire, encompassing views of New York City and State, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington and Mt Vernon.119 Seven Arms of the States were represented: Georgia, Maryland, Masschusetts, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Virginia. Views of New York had graced his dining room wall, the platters carefully arranged by size in descending order. (Fig 8) He possessed New York from Weehawken, the Junction of the Sacandaga and Hudson Rivers, New York from Brooklyn Heights, Esplanade and Castle Garden and the scarcest of all, View of Governor’s Island. Taking pride of place above these American views was a Harewood House ‘acorn and oak leaf border’ platter by Stevenson with four medallions of Washington, Lafayette, Jefferson and Clinton at the top and the Erie Canal at Albany at the bottom (lot 54), deemed to be in a class of its own. Reputed to be the only known copy, the ‘outstanding offering of the Hudnut collection’, it graced the front cover of the catalogue (Fig 9).120 Such incongruity, a famed English house overprinted with American heroes, offered the collector an interesting anomaly; it sold for $1200. 121

Old Blue Staffordshire certainly enjoyed ‘appreciation not depreciation’122; record prices were achieved, the principle buyer being Henry Woods, largely acting on behalf of Hearst. Even damage was tolerated when the view was rare; Hudnut’s Brooklyn Ferry platter with ivy border, although mended with three rivets, still made $325, as to obtain it in proof condition was deemed impossible (Lot 44). Some of the best collections lacked this view: Tompkins was never able to secure it. Esplanade and Castle Garden(Lot 22), ‘perfect in colour-the most difficult shade of blue to obtain, probably the rarest of all New York platters’, achieved $675.123 Rarity and ‘proof’ condition guaranteed top price: View of Governor’s Island (Lot 42), considered virtually unobtainable as specimens were in collections ‘not apt to be sold’, was the star lot realising $1350.124 Values had escalated sharply; in the Percy R. Pyne sale of 1917 a View of Governor’s Island plate sold for $220 and at the Kellogg sale for $425.125 Hudnut commended the aesthetic qualities of this ten-inch soup plate, ‘one of the most beautiful [views]… its colour the best blue known’.126 In terms of relative values, it is salutary to note this view realised a higher price than a plate from ‘General Washington’s Dinner set’ (Lot 57), the famous Cincinnati china, which sold for $1250. Commissioned by Major Samuel Shaw this Chinese armorial service was purchased by Henry Lee for George Washington; Hudnut declared a collection of historical china was incomplete without an iconic Cincinnati piece.127 At the Elinor Gordon Sale, Sotheby’s 23rd January 2010, an Order of the Cincinnati plate (Lot 70) realised $67,500. By comparison the Arms of Pennsylvania sold for $30,420, Delaware for $9,945 and North Carolina for $3,744 in April 2010.128 The Syntax series commandeered a wall of Hudnut’s dining room (Fig 10). Acquiring the whole Syntax set proved a challenge as subjects occasionally straddled cup-plates; Drawing from Nature (Lot 139) required two to complete the picture. At auction the ‘rarest Syntax platter’ Harvest Home (Lot 145) achieved $260; Dr Syntax Entertained at College (Lot 148), on a deep fruit-bowl, made $250 as only two examples were known. Pride of place was taken by a Soup Tureen and Cover (Lot 147), a ‘unique piece’, with Dr Syntax and the Gypsies on each side, The Banns Forbidden on the cover and Dr Syntax Setting out on His Second Tour, on the inside base (Fig 10). This made $1200! Hudnut also acquired all seven Wilkie scenes, including the elusive Errand Boy platter.

L.J. Buckely’s 1928 price guide charts the record breaking prices achieved at the Kellogg and Hudnut sales: Mayer’s Arms of Connecticut achieved $1800 (Kellogg) and Delaware $1400 (Kellogg); R. Stevenson’s Bunker Hill, $475 (Kellogg); A. Stevenson’s Junction of Hudson and Sacandaga $370 (Hudnut); R. Stevenson’s Esplanade and Castle Garden, New York $1100 (Kellogg) and A. Stevenson’s View from Governor’s Island $1350 (Hudnut). These rarities now belonged to one man: William Randolph Hearst. Epilogue Hearst’s fortunes peaked in 1928, mining, ranching and forestry providing the means to build one of the world’s greatest art collections but the economic collapse of the Great Depression revealed the vast-over extension of his empire. Unable to service its debts, Hearst Corporation faced a court-mandated reorganization in 1937. Newspapers and other assets were liquidated; a well-publicized auction of art and antiquities was held in 1938 but the creditors did not recoup Hearst’s original outlay, as this sample demonstrates: A flurry of activity in the saleroom- Stanley H. Lowndes (1935), Mrs John C. Tomlinson (1935), Eugene Tompkins (1937), Mrs John E. Alexandre (1937), Winthrop Brown (1937) culminating in the W.R. Hearst sale (1938)- inspired Sam Laidacker’s The Standard Catalogue of Anglo-American China from 1810 to 1850 (1938) and a series of supplementary price guides. Laidacker established The American Antiques Collector, a journal apparently begun to discuss and study American historical views on Staffordshire china and to report on sales of Americana.132 Once again, with America at war, sentiment fuelled the market for historical Staffordshire; the 1940s saw a series of remarkable sales: Mary Margaret Yeager (1943), George Horace Lormier (1944) and Mrs J Amory Haskell (1944-45).133 In the post-war climate, Old Blue Staffordshire fell from favour but by 1971 journalist Marvin D. Schwartz noted that historical Staffordshire was ‘coming into its own again after years of neglect’.134 The founding of the Transferware Collectors Club in 1999 and the launching of Patriotic America: Blue Printed Pottery Celebrating a New Nation, a joint venture of the TCC, Historic New England and Winterthur in October 2011, will ensure continued interest. But only one Old Blue Staffordshire Closet has survived in the public domain; the Blue Staffordshire Room, at the Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum, Delaware. Du Pont’s first Old Blue auction purchases were made at the Kellogg and Hudnut sales.135 The Morse Collection also remains intact at the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester. They are rare survivals that illuminate a moment in the history of collecting, when humble Old Blue Staffordshire could command a king’s ransom and was commandeered to fashion china closets equalling those of the 18th century. While the view added patriotic, sentimental and financial value to ‘good pieces of blue’, its aesthetic worth was determined by its hue. Sources and acknowledgments Auction catalogues, periodicals and books were consulted at the Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum and Library; many are annotated in unknown hands. This paper was made possible by a Fellowship from the Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum and Library, Delaware (2009); I would particularly like to thank Rosemary Krill, who looks after the Fellows and the Library Staff, especially Emily Guthrie, NEH Associate Librarian and Lauri Perkins, Assistant Librarian. Thanks also to Lonnie Dobbs, Anne McBride and Alana Stati, curatorial intern at Winterthur; Ted Gallagher of the TCC Board and Pat Halfpenny. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 1 Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers, The lives and careers, the deals, the finds, the collections of the men and women who were responsible for the changing taste in American antiques, 1850-1930. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1980, p. 65. 2 Oriental Old Blue, Old Blue Willow and Old Blue Staffordshire were central to the phenomenon known as chinamania, an expression coined by George du Maurier in the 1870s to satirise the cult of china collecting. Du Maurier’s first cartoon was ‘The Passion for Old China’, Punch or the London Charivari, Vol.66, 2 May 1874, p.189. 3 ‘Ten years ago there were probably not ten collectors of Pottery and Porcelain in the United States. Today there are perhaps ten thousand’, William Cowper Prime, Pottery and Porcelain of All Times and All Nations, With tables of factory and artist’s marks for the use of collectors, New York: Harper & Brothers 1878, p.5. Prime, author of the first comprehensive guide to ceramics in America, was Professor of History of Art at Princeton. 4 Walter A. Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, Being a book of ready reference for collectors, New York, Century Company, 1910, p.195. 5 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.195. 6 R.T. Haines Halsey, Pictures of Early New York on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery, together with pictures of Boston and New England Philadelphia, the South and the West, New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1899, p.xv. His collection was sold in 1943: Historical Blue Staffordshire…the collection of R.T. Haines Halsey, Sotheby Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, Nov 11-12, 1943. 7 Walter Hamilton, The Aesthetic Movement in England, London, Reeves & Turner, 1882, pp. 99-100. It was Charles Lamb who coined the expression ‘old blue china’ to describe his Oriental tea ware; Charles Lamb, ‘Old China’ (1823), Essays of Elia, London, Morley’s Universal Library, 1885, pp.148-9. By the 1870s the expression Old Blue had become a euphemism. Although the chief interest was Chinese blue-and-white, namely K’ang Hsi [1662-1722], Yung Cheng (1723-35) and Ch’ieu Lung [1736-95] porcelains, collectors were also attracted to early English porcelains, such as First Period Worcester and Caughley, printed earthenware, notably Spode and Willow pattern, and all forms of Delft. See Patricia O’Hara, ‘The Willow Pattern that We Knew”: The Victorian Literature of Blue Willow’, Victorian Studies 36, (Summer1993), pp.421-42. 8 ‘The Six Mark Tea-pot’, Punch or the London Charivari, Vol. 79, 30 Oct1880, p.194. 9 Stacey Pierson, Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560-1960, Bern, Peter Lang, 2007, p. 69. 10 Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace has made an extensive study of china as a trope for the feminine within an 18th century context; Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping and Business in the Eighteenth Century, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. 11 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.226. Author and journalist, Dyer was the managing editor of Country Life in America from 1906 to 1914. An expert on furniture, his books include Early American Craftsmen (1915) and Handbook of Furniture Styles (1918). 12 Earle could ‘fully appreciate Oscar Wilde’s sigh of “trying to live up to his blue and white china”’. Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America,New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892, p. 423. 13 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, 226. For the Cult of the Grandmother see Celia Betsky, ‘Inside the Past: the Interior and the Colonial Revival in American Art and Literature 1860-1914’, in Alan Axelrod (ed) The Colonial Revival in America, Winterthur, Delaware, The Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1985, p.248. 14 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.201. 15 Alexander T. Hollingworth, Old Blue and White Nankin China, Odd Volumes 26, London, privately printed, 1891, p.16. A noted collector, Hollingsworth was the founder of Engineering an Illustrated Weekly Journal. 16 Homer Eaton Keyes, ‘Prefatory Note’, Ellouise Baker Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China, New York, Doubleday, Doran & Co, 1939, p.xi. 17 Alexander M. Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections of Old Blue Staffordshire China’, American Homes and Gardens, IV:1, January 1907, pp.21- 27. 18 Hudnut’s male and female connoisseurs number: 19 The William Randolph Hearst Collection Part II, Early American Furniture and Historical Blue Staffordshire, Nov 17-19th, 1938, New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries. 20 Earle, China Collecting in America, p.381. 21 Jane W. Guthrie, ‘Old Blue and White’, Godey’s Magazine, February 1898, p.152. 22 William Cowper Prime, ‘Introductory’, Annie Trumbull Slosson, The China Hunter’s Club, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1878, p.8. 23 Mrs N. Hudson Moore, The Old China Book including Staffordshire, Wedgwood, Lustre and other English Pottery and Porcelain, New York, Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1903, p.2. 24 Prime,‘Introductory’, p.6. 25 Talia Schaffer, Forgotten Female Aesthetes: Literary Culture in Late Victorian Britain, Charlottesville and London, University Press of Virginia, 2000, p.82. 26 Grant McCracken, Culture and Consumption New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities, Bloomingdale and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 1988, p.53. 27 Schaffer, Forgotten Female Aesthetes, p.81. 28 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.22. 29 Earle, China Collecting in America,p.1-2. 30 Slosson, The China Hunter’s Club, p.137. 31 Slosson, The China Hunter’s Club, p.159. 32 Her collection was sold in 1912; Historical China and other objects… Miss Frances Clary Morse, American Art Association, NY, March 6 1912. 33 Edwin AtLee Barber, Anglo-American Pottery Old English China with American Views. A Manual for Collectors, Philadelphia, Patterson and White Company, 1899. A pioneer in the field of Americana, Barber’s real passion was ‘native’ pottery, his mission being to interest Americans in their own ceramics. He rediscovered Pennsylvanian Tulip Ware, alongside slip-decorated and sgraffito wares. He was considered the leading American authority on all ceramics both made and used in American being called to assess the James Ten Eyck collection given to the Albany Institute of History and Art in 1909 34 Halsey, Pictures of Early New York, p.xvi. 35 Stillinger, The Antiquers, p.204. Halsey worked on the stock exchange from 1899 to 1923, when he retired to devote his time to the American Wing. 36 Old China ran alongside Robineau’s other publication, Keramic Studio. Robineau placed his own collection of largely English scenes on the market around 1910. Samuel E. Robineau, Old China Price list of a very fine collection, old Staffordshire ware and miscellaneous pieces of old china, offered at private sale, Syracuse, NY, Keramic Studio Publishing Co. 37 See Homer Eaton Keyes, ‘The Boston State House in Blue Staffordshire’, Antiques, 1:3, March 1922, pp. 115-120. 38 Arthur H. Merrit, ‘A Recent ‘Find’ A six and one-half inch rare plate with the flower and fruit border is found in an Indiana town’, The Antiquarian, 6 January 1926, p.19. 39 Ada Walker Camehl’s The Blue China Book, New York, E.P. Dutton, 1916, p.xiii. 40 Halsey, Pictures of Early New York on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery, p.xiii. 41Simeon Shaw’s 1829 account of the Staffordshire potteries noted the introduction of red, green and brown transfer printed patterns; History of the Staffordshire Potteries and the Rise and Progress of the Manufacture of Pottery and Porcelain [1829], Great Neck, New York, Beatrice C. Weinstock, reprinted 1968. 42George L. Miller, ‘A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880’, Historical Archaeology, 25, 1, 1991, p.9. 43 Catherine Fennelly Something Blue Some American Views on Staffordshire, Old Sturbridge: Old Sturbridge Booklet Series, 1967, p.4. 44 Alexander M. Hudnut, ‘Foreword’, The Hudnut Collection Old Blue Staffordshire and other china of historical interest; Historical Old Blue Staffordshire Also Staffordshire decorated with Dr Syntax and Wilkie Views and some miscellaneous china of historic interest and value. American Art Association, New York, Thursday November 4th, 1926, p.11. 45 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.198. 46 Halsey, Pictures of Early New York, p.xv 47 Prime, Pottery and Porcelain, p.245. 48 Earle, China Collecting in America, p.316. 49 Trade resumed after the Treaty of Ghent, December 24 1814, which officially ended the War of 1812. Over 80 Staffordshire firms supplied the North American market in the period c.1815-60. Wedgwood, Minton and Spode did not participate in the market for dark Blue Staffordshire. 50 Ann Smart Martin, ‘Magical, Mythical, Practical, and Sublime: The Meanings and Uses of Ceramics in America’, Robert Hunter (ed) Ceramics in America 2001, Hanover and London: Chipstone Foundation, 2001, p.35. 51 James and Ralph Clews did produce a short series marked VIRGINIA but the views are fanciful and do not appear to have been based on topographically correct sources. 52 Moore, The Old China Book, p.20. 53 The interest in scenic views may account for the success of the Syntax series, which lampooned Rev William Gilpin (1724-1804), a Hampshire clergyman, who toured England in search of the Picturesque. 54 Moore, The Old China Book, pp.19-20. 55 Julia D.S. Snow, in a series of articles in Antiques, has revealed the widespread borrowings of the Staffordshire potters in search of American views ie Carey’s Picturesque View of American Scenery (1820), William Birch’s Country Seats of the United States of North America (1808) and Goodrich’s Picture of New York and the Stranger’s Guide(1818). 56 Wall undertook his sketching tour in 1818; his drawings were identified by L. Earle Rowe. 57 Colonial Furniture and Old English Silver, the Collection of Robert L. Forrest, Esq, Philadelphia, Anderson Auction Company, New York, February 5-6th 1912. 58 Malcolm Vaughan, ‘The Vogue of Blue Staffordshire’, Crockery and Glass Journal, 103:24, Dec 16 1926, p.115. 59 Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections’, p.27. 60Alexander M. Hudnut, ‘A Tribute to the Late George Kellogg’, The Collection of the Late George Kellogg Amsterdam, NY American Art Association New York Nov 6-7th, 1925, p.11. 61 Mabel Woods Smith, Anglo-American Historical China Descriptive catalogue with prices for which the pieces were sold at the New York Auction Art Galleries in the years 1920, 1921, 1922 and 1923, Chicago, Robert O. Ballou, 1924. 62 Rare Historical Blue China Antique Chinese Porcelains and exceedingly scarce etchings and prints. American Art Galleries New York, March 25th and 26th 1903. 63 Vaughan observed its record price had caused attics and cellars to be so thoroughly ransacked that a number of platters had come to light and consequently it was no longer so rare. Vaughan, ‘The Vogue of Blue Staffordshire’, p.115. 64Moore, The Old China Book, p.24. 65 Alexander M. Hudnut, ‘Dark Blue Staffordshire. The Dr Syntax Poem’, p.175. 66 Moore, The Old China Book, p.33. 67 Moore, The Old China Book, p.263, cites 21 in the series. 68 Walter Randell Storey, ‘The Don Quixote Series Dark Blue Staffordshire Tableware of a Century Ago’, The Antiquarian, 4:5, June 1925, p. 34. 69 L.J. Buckley, Antiques and Their History, Binghamton: Buckley of Binghamton, 1928, p.198. This was probably the W.F. Sheeley collection sold at auction to Mr Ira Kutz. 70 Hudnut, ‘Dark Blue Staffordshire. The Dr Syntax Poem’, p.178. 71 For the devout, Enoch Wood manufactured a ‘scriptural’ series in dark Blue Staffordshire, Christ and the Woman of Samaria being indicative; Barber enumerated some sixty scriptural titles. His ‘Directory’ numbers those with a preference for Biblical views, including Mrs James J.B. Neal of Easton; Barber, Anglo-American Pottery, p.195. 72 Robineau, Old China Price List, p.25. 73 Moore, The Old China Book, p.59. 74 Dyer, The Lure of the Antique, p.213. 75 See Robert Copeland, Spode’s Willow Pattern and Other designs after the Chinese, New York, Rizzoli International Publications, 1980. 76 Candace Wheeler, Principles of Home Decoration with Practical Examples, New York, Doubleday, Page & Co, 1908, p.65. 77 Guthrie, ‘Old Blue and White’, p. 159. 78 Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections’, p.21. 79 Barber, Anglo-American Pottery, p.192. 80 Hollingsworth, Old Blue and White Nankin China, p.28-9 81 Joshua Ruff and William Ayres, ‘H.F. Du Pont’s Chestertown House, Southampton, New York’, Antiques, 160, 1 July 2001, p. 102. The house was acquired in 1924 and completed in 1926. 82 Ruff and Ayres, ‘Chestertown House’, p.103 83 ‘Blue and White China’, The Art Amateur: a monthly journal devoted to art in the household, 5: 2, July 1881, p.41 84 Alice M. Kellogg, Home Furnishing Practical and Artistic, New York: Frederick A Stokes, 1904, p.20. 85The china closet Pendleton created in his own home, 72, Waterman Street, Providence, was illustrated in the Antiquarian, 4:5, June 1925. 86 ‘Dr Merritt’s Collection of Blue Staffordshire, events pottery, serious, humorous, picturesque’, The Antiquarian, 3:6, January 1925, p.20. Merritt published ‘The Romance of Old Blue China’, reprinted from The New-York Historical Society, Quarterly Bulletin, October 1944. His collection went to the New York Antiquarian Society. 87 ‘Mr Deming Jarvis’s Collection of Chinese Porcelain at Detroit, USA’, Connoisseur, 1:3, Nov 1901, p.136. 88 ‘Curio’, ‘Private Collections Dr Hammond’s Bric-a-Brac’, The Art Amateur,1:1, June 1879, p.13. 89 Kellogg, Home Furnishing, p.210. 90 Kellogg, Home Furnishing, p.211. 91 Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections’, p.22. 92 Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections’, p.21. 93 Barber, Anglo-American Pottery, p.193; Moore, The Old China Book, p.45-6. 94 Edwin Morse was a partner in Lathe and Morse, a machine tool company. 95 Catalogue of the Morse Collection of American Historical Pottery, Worcester, Mass, Worcester, Mass, American Antiquarian Society, 1916. 96 Guthrie, ‘Old Blue and White’, p.154. 97 ‘Art at Home and Abroad. Interest in Mrs Abraham Lansing collection of pottery at the Metropolitan Museum and the Ten Eyck gift to the Albany Historical and Art Society’, New York Times on-line Sept 11th 1910. Abraham Lansing (1835-1899), from an illustrious family of Dutch extraction, was a lawyer active in politics and civic affairs. He was the cousin of Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick. 98 ‘.....Ten Eyck gift to the Albany Historical and Art Society’, New York Times on-line Sept 11th 1910. 99 Thomas Mayer of Cliff Bank Works, Stoke manufactured dark-blue printed ware from c. 1825-35. 100 Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China, p.123. That Mayer knew there were 13 States is attested by his printed back-stamp, which included 13 stars and the motto E Pluribus Unum. 101 Moore, The Old China Book, p.95. 102 Her husband, Richard Vliet (1850-1925), a noted scholar of Elizabethan drama, was a successful lawyer, who acted as General Counsel for the Prudential Life Insurance Company. 103 Marshall Littlefield Hinman (1841-1907) was Mayor of Dunkirk and founder of the Brooks Locomotive Works. 104 Hudnut, ‘Some Notable Collections’, p.26. 105 The Louise G. Garland and Gwendolyn Garland Babock bequest was de-accessioned in 2003. Parts were consigned to Northeast Auctions, Portsmouth, NM, in 2004 and 2013 (Lots 1-17) and (242-262). My thanks to Dr Rosie Mills, Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross Associate Curator, LACMA for this information. However, an inventory taken in 1985, when the collection was acquired by LACMA, is extant. 106 WWW. The Ancestry of John Jewett Garland by Gwendolyn Garland Babcock, accessed 15/01/2012. 107 ‘Eugene Tompkins’, New York Times on-line, Feb 23 1909. 108 The collection was sold in 1937. Historical Blue Staffordshire China-Collection formed by the late Eugene Tompkins with examples from the Collection of the late Mrs John E. Alexandre, New York: Anderson Galleries, 1937. 109 ‘George Kellogg’, New York State Men, Albany, NY: Argus Art Press, 1919, p.6. 110 Historical Old Blue Staffordshire…the collection of the late George Kellogg, Amsterdam, New York, New York: American Art Association, November 6-7 1925. 111 Clews’s States Border Series or the America and Independence series combines a central view flanked by two female personifications respectively labelled ‘America And’ ‘Independence’ surrounded by a border of festoons bearing the names of the fifteen states. Mrs Hudson Moore considered the series offered many pleasing varieties, as there were at least a dozen different central views. Her example, with the ‘White House, Washington’, sold at the Haigh Sale (1902), Boston, for $46. However, all fourteen views in this series utilised English locations, all bar one taken from Marshall’s Select Views in: Great Britain &c (1825-28), a ‘topographical history of remarkable Places and beautiful Seats in the Kingdom’. See Dick Henrywood,’ The States Border Series by Ralph and James Clews’, Robert Hunter (ed) Ceramics in America, 2011, Hanover and London, Chipstone Foundation, 2011, pp.101-110. 112 ‘George Kellogg’, p.8. 113 ‘Remainder of the Historical Staffordshire, Copper and Lustre’, New York Times on-line, March 27, 1903. 114 ‘China sales net $30,490 Highest Price Yesterday, $1,100 for a Staffordshire Platter’, New York Times on-line, November 8 1925. 115 ‘Soda Water’, The Independent, April 25 1878, p.1534. 116 ‘Hudnut Sells Out’, New York Times on-line, Dec 31 1889. 218 and 203 Broadway were sold in 1889 for $250,000. His son Richard Hudnut carried on the drugstore business, creating the Du Barry line, the first range of fragrances and cosmetics made in America. 117 A partner in Halsey & Hudnut, he was a member of the Century Association and New York Water Color Club. Paintings and Drawings of John Francis Murphy: the only large collection of Murphy’s works; paintings presented by the artist to his wife and sketches and drawings never offered for sale before, American Art Association, New York, 1926. 118 The Important Library of Alexander M Hudnut of New York City: Doves, Essex House and Kelmscott Presses, first editions of Dickens, Thackery, Kipling, American Art Association, New York, 1926. 119 The Hudnut Collection Old Blue Staffordshire and other china of historical interest; Historical Old Blue Staffordshire Also Staffordshire decorated with Dr Syntax and Wilkie Views and some miscellaneous china of historic interest and value. American Art Association, New York, Thursday November 4, 1926. 120 Stevenson and Williams repeated this combination using Oatlands Park, Surrey, Writtle Lodge, Essex and Windsor Castle. 121 Another ‘very rare plate’ also featured the Erie Canal at the bottom; the St Paul’s Chapel plate also had a medallion of Washington (lot 34), an appropriate combination as Washington attended services here. Hudnut gathered most of the plates featuring New York’s churches: St Patrick’s Cathedral, Mott Street; Dr Mason’s Church in Murray Street and Church and Buildings Adjoining Murray Street being the scarcest. 122 David and Linda Arman, First Supplement Historical Staffordshire: an illustrated check list, Danville, Virginia: Arman Enterprises, 1977, p. 2. 123 The Hudnut Collection, p.18. A marginal notation in unknown hand notes Hudnut had paid $500 for this specimen some thirty years before. See also Hudnut, ‘Dark Blue Staffordshire Historical China Depicting American Scenes’, p.237; here Hudnut disingenuously claims collectors had paid as much as $500 for this view. 124 The Hudnut Collection, p.22. 125 The Notable Percy R. Pyne the Second, Collection, American Art Galleries. 126 Hudnut, ‘Dark Blue Staffordshire Historical China Depicting American Scenes’, p. 238. 127 The Hudnut Collection, p.26. 128 Through Pook and Pook, Maine Antiques Digest April 2101, Transfer Collectors Club, accessed 15/01/2012. 129 The William Randolph Hearst Collection Part II, Early American Furniture and Historical Blue Staffordshire, Nov 17-19 1938, Parke-Bernet Galleries, NY. No images have been located of the collection in situ. 130 Historical Blue Staffordshire China collection formed by the late Eugene Tompkins and from the collection of the late Mrs John E. Alexandre… American Art Association, February 19th 1937. 131 Mary Margaret Yeager Sale, Parke-Bernet, New York, March 20 1943. 132 Sam Laidacker, Auction Supplement to the Standard Catalogue of Anglo-American China…during the period June 1944-Jan 1949. Bristol, PA: Sam Laidacker, 1949. 133 George Horace Lorimer Part 1 Parke-Bernet, New York, March 29, 30, 31, April 1, 1944. 134 Marvin D Schwartz, ‘Antiques: Staffordshire Is In Again; Public Shows Growing Interest in Pottery’, New York Times on-line, June 26, 1971, p.33. 135 From the Kellogg Sale. |

|||||||||||||

The Romance of Old Blue • Issue 15 |