Interpreting Ceramics | issue 15 | 2013 Conference Papers & Article |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

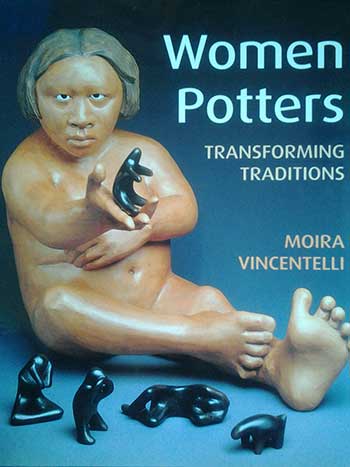

Clashing with Clay Mother: Pueblo potters who subvert the traditionMoira Vincentelli |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

This text is based on a paper presented as a paper at the Subversive Ceramics: Exploring Ideas in Contemporary Ceramic Practice symposium at the Holburne Museum, Bath, 9 November 2012. The article hinges its argument around the metaphor of ‘Clay Mother’ which is widely used among Native American cultures and in particular Pueblo people of New Mexico. By definition Pueblo potters work within a particular ‘tradition’ which conserves ideas from the past. Much Pueblo pottery has been developed for the Anglo market of tourists, galleries and collectors and conforms to notions of the ‘good’ Indian producing finely crafted work. But some potters have used their work to be more challenging whether to the contemporary global culture or their own Pueblo society. Artists discussed include Carolyn Concho, Nora Naranjo-Morse, Roxanne Swenzell Christine McHorse and Diego Romero. Introduction A major focus of my research has been what I have dubbed women’s traditions in ceramics. By that I mean situations where pottery is seen as a female activity and even used to define the feminine in a particular society. Such pottery is largely hand built, fired in a bonfire or very simple kiln and is mainly functional or perhaps ceremonial, in which case it might include figurative forms. Over the last century in many places this type of pottery has adapted to new markets for planters, house decoration and tourism. As it becomes economically significant or more valued, gender shifts take place and men begin to take up the work. One of the most successful of all these women’s traditions is that of Pueblo pottery from New Mexico. Like so many, it is an ‘invented tradition’. As the history of the Southwest was documented and constructed through the work of archaeologists, anthropologists and specialist scholars, distinctive types and styles of ceramics became signifiers of peoples and places in certain periods. This essay considers how Pueblo potters, who by definition work within a particular ‘tradition’ and are to some extent subject to the Pueblo jurisdiction, are able to operate in ways that are subversive either in relation to their own culture or in the context of the wider global art world. I first visited New Mexico in the 1990s when I undertook museum and library research and met potters whenever I could. For this article I am drawing on a number of short interviews that I made with potters on a return visit in April 2012.1 There have been settled peoples in the Rio Grande valley for over one thousand years; in the seventeenth century the area was colonised by the Spanish. In 1846 New Mexico was annexed to the USA and finally made a state in 1912. The area was opened up to the world when the railroad reached Santa Fe in 1880. Around this time Native American children were being taken away from their families to be educated in boarding schools and acculturated into the ‘American’ way of life under the assimilation programme. In the Spanish period Pueblo pottery had survived quite successfully as the colonisers had used it rather than setting up European style workshops with wheels and kilns as in many other parts of the Americas.2 By the late nineteenth century, however, pottery production was in decline as manufactured goods became increasingly available. Revival In the early twentieth century under the influence of Anglo3 archaeologists, anthropologists and philanthropists working in New Mexico and themselves influenced by the ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Pueblo pottery was revived, taking it to great heights of virtuosity. The potters increasingly produced work for Anglo tourists and collectors and pottery was even sold by mail order. One of the ways that the archeologists and museum advisors worked was by suggesting that potters ‘revive’ older styles. At Hopi it was early Sikyatki wares; at San Idelfonso it was black on black wares; and at Acoma it was Mimbres pottery from circa 1200 AD. Almost unknown till the early twentieth century when archaeologists began to find it in grave burials, Mimbres bowls quickly became highly collectable and admired for their delicate geometric and illustrative designs.4 Lucy Lewis’ daughter recalled that: Our family would buy books to look up the old pottery designs and Dr, Kenneth Chapman from the Museum of New Mexico suggested to us to use the Mimbres designs.5 The revival of Pueblo pottery is part of the history of twentieth century ceramics in the USA; however it is rarely integrated as part of the story of contemporary work. Like most work that comes out of women’s traditions in ceramics it is marginalised and largely categorised through museums in the context of anthropology and culture rather than the visual arts. Nevertheless since the early twentieth century there has developed a buoyant market for Pueblo pottery in the USA and collectors flock to Santa Fe in August for what is known as Indian Market. The medals and prizes awarded at this event are proudly cited by potters and are important markers of status. Indian Market was first begun in 1922 and until relatively recently the judging was dominated by dealers and Anglo collectors who encouraged particular qualities and style categories.6 Santa Fe itself is full of art galleries of all types and among these there are a number who specialise in pottery. A photograph of the Andrea Fisher Gallery shows how the display is organized according by particular Pueblo styles with a map in the background showing the different pueblos. (Fig.1)

In many places where working in clay is a strongly gendered activity and women are the designated potters, the material they use, namely clay, takes on female associations. For Pueblo potters the material itself – ‘the dirt’ or the earth is conceptualized as female. Pueblo potters frequently make reference to Clay Mother, Grandmother Clay or Mother Earth. Respect has to be shown to her including, at times, with offerings and rituals. She protects and conserves life, is associated with nature and almost by definition stands for conservative values against the threats to American Indian culture in the modern world. Each Pueblo has a distinctive type of decoration and although, within a certain range, this constantly evolves, potters like to respect these boundaries. Issues of authenticity abound. Firstly, in terms of family inheritance, as most potters learn from an older relative; occasionally this may be a relative by marriage. Secondly, the process itself is vital to lending authenticity to a work. The clay is dug from particular places under the jurisdiction of the Pueblo, the pieces are made by hand building (not thrown on a wheel and not slipcast), they are usually burnished and finally the work is fired outdoors in an open firing rather than a kiln. Of course these rules are confirmed by the very fact that they are frequently contravened – as we shall see. Nevertheless, the high level of craftwork is constrained by the need to be true to the ‘tradition’ and tied up with issues of identity, authenticity and economic value. In some senses, the idea of the subversive in Pueblo ceramics is reflected in the whole tradition which can be seen as asserting minority identity in a dominant culture. For well over a century Pueblo peoples have resisted what seemed like the inevitability of their decline and eventual disappearance fusing into the melting pot of contemporary American culture. Pottery has actively been used to promote Pueblo culture and signal identity, even ‘otherness’, but within that context, it is intrinsically conservative. Here I am reminded of a writer whose work is now little discussed, namely Nicos Hadjinicolaou, who in the 1970s in his Art History and Class Struggle developed the idea of ‘positive visual ideology’ and ‘critical visual ideology’.7 According to Hadjinicolaou most artists make work that affirms the values of the dominant society or patron but sometimes artists are able to critique the status quo. Pueblo pottery is a marginalised field within the wider field of contemporary ceramics in the USA. Mostly it knows its place, keeping its distinctive look and using its traditional techniques to display high levels of craft skill and fine finish. In so doing it affirms the values of the dominant North American culture as constituted by the arbiters of taste - the tourists, collectors, museum curators and dealers. It stands for the preservation of disappearing knowledge, of good craft values and even has an element of romantic frisson with the idea that such work will soon disappear. That makes it all the more collectable. Carolyn Conchito, Acoma Carolyn Conchito is one of the best known potters at Acoma or Sky City, a Pueblo situated on a high mesa above a dramatic landscape. Few people live there all the time but even on a snowy day in April 2012 when I visited there were people standing by their tables hoping to sell pottery, carvings and jewellery. At the base of the mesa there is a very well appointed reception centre with a café, displays and areas for selling. Acoma is well known for its white clay pottery with delicate designs in complex geometrics or with Mimbres-inspired figurative elements of animals and insects. Carolyn Concho showed me one of her exquisitely decorated pots and explained the work thus: (Fig. 2)

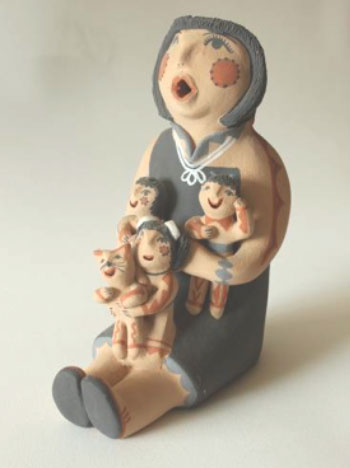

This piece, I would argue, exhibits positive visual ideology. It has a high degree of skill, is beautifully finished and is decorated with recognizable motifs in the Mimbres/Acoma style. Concho emphasises that it is all ‘natural’ by which she means that the work is made from local clay, built by hand, not slip cast, and decorated with earth colours rather than commercial paints. It is a common trope for potters to use ‘natural’ to lend authenticity to their work. She gives an explanation for different design motifs suggesting their relationship with the natural world. The more abstract patterns are related to popular conventional Pueblo symbols while the more realistic animal and insect forms are also given meaning but she suggests they are personal symbols. This plays to the desire of the buyers to read art works as ‘original’, not something that would have been important in earlier centuries. Finally she admits, a little reluctantly, that she fires in an electric kiln ‘as they come better’. Thus she steers a careful path through the traditional and the innovative. I offer this as an example of positive visual ideology and want to contrast it with works that might be interpreted as having a more critical edge. The earliest of these can be seen in figurative pieces. Early figurines The figurine was a rare form in the pre-colonial period. By the colonial period priests and educators would have almost certainly discouraged them as idols. Figurative work seems to have reappeared in the 1880s, possibly emerging from indigenous initiatives but quickly encouraged by Anglo traders such as Aaron Gold. This period coincides with the opening up of the railroad and increasing contact between Anglo and Pueblo peoples. Jonathan Batkin has shown how the crudest of these figurines, known as rain gods, were sold widely by mail order and bought by Anglo Americans as curiosities that surely confirmed the ‘primitive’ otherness of Native American culture.8 At a more sophisticated level and particularly associated with Cochiti Pueblo are larger modeled and painted figurines, or monos of contemporary types. Nearly always male, these figurines of cowboys, circus figures or priests are the new men of the modern world and the dominant Spanish and Anglo culture. Seen through the subaltern9 eye of the Pueblo women potters, Cochiti figures are humorous observations with a satirical edge. Buyers would have seen them as ‘curios’ and they were not collected for their aesthetic value. Significantly there are no known names for the makers of these works. (Fig. 3) Cochiti figures had been little valued in the first half of the twentieth century and few museums collected them. They would have been read as ‘inauthentic’ hybrid products developed purely for a market and not to be compared with the apparently functional bowls and jars, finely decorated and produced by known women potters. With the huge expansion of revival pottery after the 1920s figurative forms were given little recognition and were rarely seen at Indian Market until after the mid twentieth century. Figurative forms became popularised again in storyteller figures developed first by Helen Cordero (1915- 1994). The story teller is the principal figure who can be male or female or even sometimes an animal, but with small ‘children’ attached to the main figure. Many potters now make versions of these group figures. They are life affirming, emphasizing family values and generational harmony and thus play to an Anglo taste for the ‘good Indian’ preserving old values and therefore conforming to a category of ‘positive ideology’. They are highly collectable. (Fig. 4)

Naranjo Family In contrast with this I want to consider a group of artists who all come from the Naranjo family from Santa Clara Pueblo. Many of the women in the family are potters and this family in particular has produced artists who have stepped out of the norm. Nevertheless all remain within the context of Pueblo inheritance and adhere in various ways to the values of ‘Mother Clay’ while using their art in combative ways. Jody Folwell (b1942) was one of the first potters to begin to make work with overt political content in the 1980s. She continues to this day to use traditional methods of handbuilding but was one of the first to make asymmetrical forms finished with careful burnishing. She records that she uses a burnishing stone passed down through generations from her mother’s grandmother. The burnishing stone is often an item of significance for women potters in New Mexico and many other places in the world. Using text and engraved lines, Folwell’s work frequently carries comment on the contemporary world – for example the Iran contra affair in 1986, a scandal about arms sales to Iran in return for the release of hostages under Ronald Reagan. Another vessel entitled ‘The Stampede’ was a comment on Indian Market and the huge competitive buying situation at that event. Her daughter Susan Folwell has inherited the genre and still makes the point that she fires in the traditional way; however her brightly painted illustrations are in acrylic. Susan Folwell’s work has addressed issues such as the politics of President Bush in Iraq ( Fig. 5) but has also tackled Pueblo politics and her perception of the paternalism and even racism of the Pueblo council.10

Nora Naranjo-Morse (b 1953) is one of eight siblings from Santa Clara Pueblo and is the sister of Jody Folwell. She was one of the new generation of makers educated at college in Santa Fe and followed that by a period of travel for some years living away from New Mexico. On her return she took up clay work and first became known for her sizable figurative sculptures. At the same time she was writing poetry and has since gone on to create work through video, film and installation. In her book of poems Mud Woman: Poems from the Clay (University of Arizona Press, 1992) she writes in the closing lines of her poem ‘When the Clay Calls’, I am in awe of this clay that fills me with passion One of her early characters was Pearlene, a modern girl standing one metre high and painted with commercial non-traditional colours. In her hands she holds little stripey koshare (clown) figures. Koshares are figures who appear at festivals and Indian dances and are given leeway to comment on social issues. It seems this young woman is taking control. (Fig. 6 Nora Naranjo-Morse Pearlene, 1994 see http://www.cla.purdue.edu/WAAW/Peterson/images/fig2-m.jpg) A later work ‘Gia’s Song’11 uses an installation format where the viewer looks into a room typical of a prefab house often seen on Indian reservations. The outside wall is covered in graffiti with slogans such as ‘destroy government housing’ and ‘Why is Leonard still in jail?’. Inside there is a typical interior with a crucifix and a television playing a video lamenting the plight of Puebloans on reservations, mourning the intrusion of government housing and the way children were removed from their parents and sent off to boarding schools. (Fig. 7 Gia's Song, see http://www.newyorkartworld.com/images-reviews/areservation/giassong-338x300.jpg) The theme of housing runs through her work, sometimes fusing the concept of figure and house in landscape installations, as in ‘Our Homes Our Selves’ (1998-9) now in Minneapolis Museum. The seven fired and painted clay sculptures look like adobe structures but have the proportions of human figures. These sculptures express a strong Pueblo sentiment and set of values but contest the conventions and strictures of Pueblo pottery. (Fig. 8 see http://www.artsmia.org/exhibitions/images/f/08-southwest-visions-mia_28002.jpg) In 2006 Naranjo-Morse won the competition to undertake a project in the area around the recently opened National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, an institution committed to re-thinking representations of indigenous peoples and led by Native American curators and educators. Using straw and mud prepared as for traditional house building she organised the construction of five sculptures 7- 16 feet tall representing a family of characters – one in the shape of a tipi others more igloo like. The constructions were based on traditional house building methods in the Pueblos and were intended to decay gradually and ‘go back to the earth’. Incorporating video recording and participant involvement, people were interviewed as the pieces were being constructed. Entitled ‘Always Becoming’ she wanted the work to convey ‘the unique relationship indigenous peoples established with their environment’.12 Thus she used her medium of clay/earth and other natural materials to assert a Pueblo presence and Native American values in the heart of Washington. (Fig. 9)

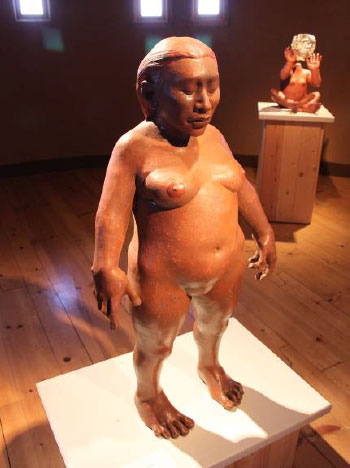

Roxanne Swentzell, who is the niece of Nora Naranjo-Morse, began to make figurative work from an early age. She tells the story that when she was as young as three she was not able to speak well and began to make little figures to express her feelings and communicate things that she could not put into words. Although she overcame this early difficulty it is as if her works continue to play that kind of role. She first came to the attention of the public through her figurative sculptures of koshare clowns. In one work the koshares emerge into the world leading the people behind them. In ‘Despairing Clown’ the figure peels off his stripes to look beneath at what he really is, eliciting in the viewer a sense of empathy with his puzzlement. Over the last twenty years Swentzell’s work has used the epic female figure as a vehicle for her message. These weighty sculptures are in some senses the epitome of ‘Mother Clay’. They assert female power. Although there is no suggestion of a direct connection, Swentzell’s approach makes an interesting comparison with the work of the British painter, Jenny Saville, whose monumental female nudes first appeared around the same time in the 1990s and challenge popular conventions of female beauty. In ‘Pueblo Figurines for Sale’ (1999) (Fig. 10) a powerful naked female figure holds out a small black figurine, finished with the high burnish typical of Santa Clara Pueblo. More black figures lie in front of the sculpture which seems to glare out at the viewer with an expression of distrust. Like an ancient sibyl or prophetess this weighty figure is a comment on the position of the Pueblo potter and, by extension, Swentzell’s own position as an artist in the marketplace. Writing about this work she asks,

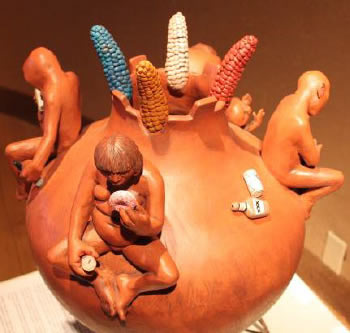

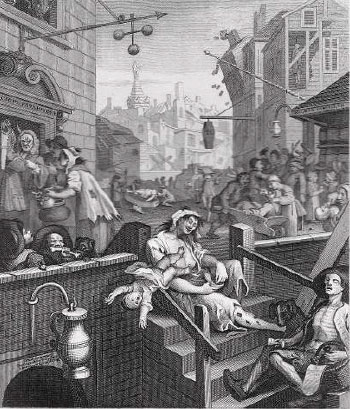

A more recent work ‘The Corn Mothers are Crying’ (Fig. 11 & 12 ) has echoes of Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’. (Fig. 13) The vessel with corn cobs protruding from its opening alludes to the legend of the Corn Mother to suggest nurture and renewal. Attached figures around the body of the vessel show the problems of modern Pueblo society: a mother slumps in despair as her baby cries, a man injects himself; a woman munches a doughnut and drinks coca cola referring to problems of obesity and diabetes while a hooded male figure cuts into the pot which bleeds. Swentzell’s work critiques her own culture and its dependence on, and destruction by, the dominant culture of the modern world.

She also looks critically at the role of the modern Pueblo artist. She has found a way of maintaining a certain independence from the dominance of the Anglo dealer by having her studio and gallery on an Indian reservation and marketing her own work. Opened in 2006 the Tower Gallery is a distinctive adobe building on the Pojoaque Indian Reservation. (Fig 14 & 15 see http://www.roxanneswentzell.net/ towergallery_aboutgallery.htm) In the carefully lit gallery she is able to show her work to dramatic effect while in the area around the outside are large scale bronze sculptures of her monumental figures. (Fig 16 ) The location is all important as the gallery is part of a community and functions as an arts and education centre.

Roxanne Swentzell has become one of the most successful Native American artists in clay and bronze but it is significant that she chooses to keep a controlling hand on the marketing and sale of her own work while maintaining a strong community commitment. Diego Romero Diego Romero was born in 1964 and raised in California. He is of mixed parentage with an Anglo mother and a father who was from Cochiti Pueblo. As an artist and teacher his father had resented the control exerted by tribal rulers on the reservation, however he did send his son to spend summer vacations at Cochiti Pueblo. Romero recalls that as a child he was taunted by other children for his mixed identity – in California he was a ‘half breed’ and even on the reservation he had to fight to be accepted. But it was there that he chose to establish his identity – and he began to develop his knowledge of Pueblo culture and social expectations. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe for one year but then went back to art education in California completing his MFA in UCLA under Adrian Saxe. Coming to maturity as an artist in the postmodern moment Romero was able to bring together his conflicted self identity by drawing on imagery and styles from very different cultures. Using his gift for drawing in a graphic style he plundered motifs from sources as diverse as Greek vase painting, Mimbres pottery, Pop Art and comic book design. He hand coils his bowls but is primarily interested in surface and will sometimes have another potter make the piece for him to decorate. The power of Romero’s work lies in the satirical and ironic comment in his lively graphics. Garth Clark has compared it to the work of Kara Walker who draws on a nineteenth century cut paper technique, a middle class white woman’s art, to comment on black and racial issues in the USA.14 Romero often signs his work ‘Chongo made’ in a playful self-deprecating way. Chongo refers to Native American men who wear their hair tied back but it also means rat in Spanish giving it a double word association. In the 1990s he developed a pair of characters, twins called the Chongo brothers, and he uses them to comment on the hollow aspirations of young (Native American) men. Body building, golf playing, fast cars and glamorous women all feature in the imagery. (Fig. 17 see http://www.metmuseum.org/collections/search-the-collections?ft=romero%2c+diego) Another of his characters is the coyote, a trickster or wild boy. In ‘Coyote and Hound’ the characters whoop it up under the cosmic night sky. (Fig. 18)

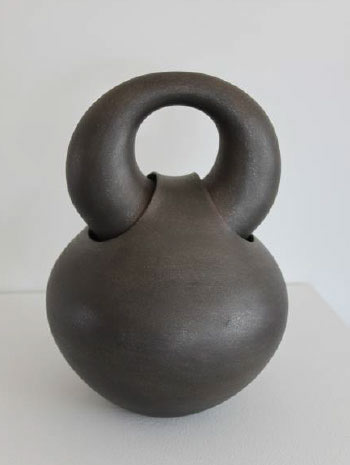

In the matriarchal world of Pueblo pottery men are the newcomers. Historically they have frequently taken on the role of the decorators in male/ female partnerships such as Maria and Julian Martinez.15 To some extent Romero could be said to have historical precedents. It is interesting then to note that his own son, Santiago Romero is also now exhibiting ceramic sculptures as can be seen in a photograph of their work showing in the Robert Nichols Gallery, Santa Fe in 2012. Christine McHorse Christine Novichissey McHorse (b. 1948) is Navaho by heritage but both her parents were from the final generation who were brought up within the assimilation programme, sent away to school and deliberately separated from their cultural roots. They never returned to the reservation. Through her grandmother she began to recover her lost Navaho heritage and, although she did not come from a craft family (her father worked as a miner), as a teenager she attended the Institute of American Indian Arts at Santa Fe. Here she met her husband who was studying silversmithing and was from Taos. His grandmother was a potter and it was through her that McHorse first learned to make pots using the distinctive micaceous clay of that Pueblo. Taos pottery is noted for its simple undecorated forms allowing the sparkle in the clay to create an effect. Navaho pottery is also characterized by its strong shapes and warm brown pine resin (pinon) used to waterproof the surface. Thus there are clear precedents to the way that McHorse has developed her work with its strong sculptural qualities and undecorated surfaces. (Fig. 19)

Conclusion In talking with Diego Romero and Christine McHorse the conversation swings in and out of positions where their sense of Pueblo identity is dominant and other moments when they stand outside it and speak as contemporary artists. (Fig. 22)

For both the need to associate their work with a Pueblo tradition is important and the particular source of clay remains an issue. McHorse still uses some micaceous clay from Taos with rights inherited through her husband’s family although she only needs small amounts and collects it only every few years. Romero, who I would not have imagined would see clay as an issue at all, also still collects clay from Cochiti Pueblo but is mostly happy to use commercial clay. He was about to run a class and needed clay but was quick to explain that there was no way he would take non Indians to collect clay at the Pueblo. Thus both remain carefully respectful of their sources of clay. For Naranjo-Morse earth and clay become metaphors for house, family and community while for Jody Folwell the burnishing stone is something that is given symbolic meaning in the way it links her to a family heritage. Many Pueblo potters still fire their work in the traditional way in open firings, often using very carefully controlled techniques. Moving over to use electric kilns can be seen as a kind of betrayal of the tradition rendering the product less ‘authentic’. Both Romero and McHorse have used open firings but now prefer the security and controllability of modern kilns. Thus material and process are meaningful in a way that is much less significant for most contemporary clay artists. When Pueblo potters choose to subvert the tradition there is more personally at stake and it may or may not have significance for the outside audience. Notions of authenticity and identity are always lurking. Clay Mother is a concept that can easily be dismissed as being a romantic notion of North American Indian culture and its harmonious relationship with nature. Nevertheless it chimes with many of the concerns that people the world over feel about the careless way contemporary society treats the resources of the natural world. What I am suggesting is that Clay Mother can be empowering and even subversive. It can challenge the internal rules of its own society but, perhaps more importantly, it can take on and critique the dominant culture. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

1 I am particularly grateful to Garth Clark and Kathryne Cyman who assisted me with contacts and introductions in the short time that I was in New Mexico. Garth Clark’s exhibition and book Free Spirits the New Native American Potter, Stedelijk Museum, Hertongenbosch, 2006 has also been an important source for this article. 2 Batkin, Jonathan Pottery of the Pueblos of New Mexico 1700-1940, Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs, 1987 p. 15. 3 In New Mexico there are three main groups within society. The indigenous peoples, include the Navaho, Apache and Pueblo people, the latter named by the Spanish thus as they lived in settled villages. They speak a variety of different Indian languages even among the pueblos themselves. Hispanic peoples were the first European settlers and speak Spanish and finally there are Anglos, or English speakers of North American and European origin. 4 For more on this see Vincentelli, Moira Women and Ceramics, Gendered Vessels, Manchester, MUP, 2000 pp. 66-72; Vincentelli, Moira Women Potters Transforming Traditions, London, A&C Black, 2003 pp 99-115. On revivals in particular see Kardon, Janet (ed) Revivals! Diverse Traditions in Twentieth Century American Craft 1920-1945. 5 Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery, Maxwell Museum , University of New Mexico Press, 1988 p.9. 6 The event was originally called Indian Fair. For more on this see Carter Jones, Meyer ‘Saving the Pueblos’ in Meyer & Royer (eds) (2001) Selling the Indian, Tucson, University of Arizona Press, pp 190-211 and Bernstein, Bruce in Changing Hands, Art without Reservation 1 (2002) New York. American Craft Museum, pp 103-106. 7 Hadjinicolaou, Nicos, Art History and Class Struggle, London, Pluto Press, 1978. In a recent discussion Richard Clemmer discusses class difference in the market for Pueblo pottery in the early twentieth century 8 Jonathan Batkin ‘Tourism is overrated: Pueblo Pottery and the Early Curio Trade, 1880-1910’ in R.Phillips and C Steiner, Unpacking Culture , University of California Press, Berkeley & Los Angeles, 1999:282-297. 9 The post colonial scholar and writer, Gayatari Spivak popularised this word in her essay ‘Can the subaltern speak’ to suggest the way that the voices of colonial subjects are easily lost or silenced in dominant accounts. 10 See for example Garth Clark, Free Spirits, p.43. 11 Gia means mother and Naranjo-Morse has also written a poem on the same theme. 12 See www.nmai.si.edu/always becoming 13 Quoted in Jonathan Batkin Clay People, Wheelwright Museum, 1999:26. 14 Garth Clark Free Spirit p. 105. 15 Maria Martinez (1887-1980) is the most celebrated matriarch of Pueblo pottery. Her husband, Julian Martinez (1879-1943), decorated her pots and developed many of the distinctive designs that made their work so notable. Later Maria worked with her sons and a daughter-in-law as decorators. 16 Confirmed by McHorse and Romero in conversation with the author. See for example Canyon Art website http://www.canyonart.com/santa-clara.htm where they give a brief description of the ceremony along with the illustrated wedding jar. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

Clashing with Clay Mother: Pueblo potters who subvert the tradition • Issue 15 |